Even if it weren’t for the grapevines of Minervois, Corbières and Limoux descending in rows down from the snow-topped Pyrenees and severe Massif Central mountains into the Aude Valley; even if it weren’t for the thousand-year-old stained glass, great Gothic arches, and layers of local marble and sandstone recalling the Paleolithic, Roman and medieval people who walked the hills and built the walls around us; even if it weren’t for the mild Mediterranean climate, encounters with the easygoing people of the Languedoc region, and the world-class delicacies they serve from their own backyard — even if it weren’t for all these things, I would come to the Midi just for the canal bridges.

The 17th-century Canal du Midi, linking France’s Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts, is a marvel. But the stone canal bridges that appear occasionally along its route are truly incomprehensible. While a white-water river tumbles underneath, canal boats pass placidly overhead. To stand beside a canal bridge is to step into a real-life, three-dimensional M.C. Escher painting.

Yet the mind that created the Canal du Midi and invented the canal bridges was not of Escher’s Modernist age but of a far earlier time, when “horsepower” referred to horses. He was Pierre-Paul Riquet (1609–1680), and it was the Sun King, Louis XIV, who enabled Riquet to sculpt his seemingly deluded aspirations into the French landscape. Riquet’s canal was one of the greatest public-works projects of its time, and its successful completion in 1681 boosted France’s economy for the next 200 years, until railroads finally superseded it.

The Canal du Midi — bypassing Gibraltar and all the complications of Spain, England and the Barbary pirates — stands today as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. As a travel destination, it deserves a top spot on the bucket list of anyone who loves to wander by water.

A Time and a Place to Celebrate

My mom loves to wander by water, and in recent years she’d occasionally suggested a canal trip in Europe as a good way for our family to gather. As much as I agreed, other priorities in our lives always seemed to nudge that notion aside.

Still, her idea had a powerful hold on us. Beginning when my sister and I were young teenagers, our family lived for several years aboard a 41-foot ketch on the Gulf Coast and in the Bahamas, and for all of us, that period remains a happy high point. In our own way, we’ve each been seeking to bring elements from our liveaboard days back into our present lives. So when we saw my parents’ 50th wedding anniversary approaching, my mom’s idea moved to top priority.

In the end, real life being what it is, we weren’t able to gather our whole family for a springtime excursion. But we did assemble a crew of seven, with a quorum from each of the generations. Representing my sister’s family was Isabel Jennings, age 11. For my daughter Kate, 16, the April anniversary coincided with her sophomore-year spring break. My mom’s sister, Rose Meagher, joined us, as did our friend Jim Bricker. And of course, there was the anniversary couple: Tom and Sue Murphy.

Our introduction to Languedoc began in Narbonne, where we spent our first night before boarding the canal boat. Narbonne is a beach town, situated less than 10 miles from the Med. It’s also a medieval town, home to the original troubadours and to the third-tallest Gothic cathedral in France, and it’s a Roman town, with the stones of the Via Domitia, the ancient road from Rome to Spain (circa 118 B.C.), running right through its central square.

“What’s the oldest thing you can touch?” became our ongoing challenge to Isabel. She’d recently touched the 800-year-old Mayan stone at Tulum, in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. But here, on her first day in Languedoc, she’d already beaten her previous record by more than a thousand years.

The Languedoc region is not Paris, just as the Carolina Lowcountry is not Manhattan. For those of us who’d spent time in the capital and thought we knew France, Languedoc was a revelation. The area is actually named for its difference from the Parisians. In the early Middle Ages, when the Romance languages were first differentiating themselves from Latin, the French language dominated northern France, while Occitan stretched through the south from the Alps to the Pyrenees. The northern French word for “yes” was oïl (now oui); in Occitan, the word is oc. And given that langue means “language,” langue d’oïl referred to the language spoken in the north, while langue d’oc — Languedoc — described the language spoken in the south. Beginning with the Fourth Crusade, around 1200, the north-south struggle for political and cultural dominance of the region was full of the horrors humankind has been perfecting for all of its history, and since then, generations of French policy have aimed to eradicate the Occitan language altogether. But still it has persisted, and since the 1970s, there’s been a popular movement to bring the language back into common use. It’s comparable to the Catalan and Galician revivals in Spain, or the Gaelic revivals in Ireland and Scotland. Throughout Languedoc today, you’ll find street signs written in Occitan as well as French. More to the point, during our entire stay, we never once met a person who fit the stereotype of the surly Parisian waiter.

Say Yes to the Garnish

I was still jet-lagged and groggy on that first night in Narbonne, still dusting off my schoolboy French, when the question came: “Vous la voulez garnie?”

After our midafternoon arrival at the Toulouse Airport, we’d rented a big diesel Mercedes van, loaded all our kit and our seven selves aboard, driven nearly two hours down the A61 national highway, and located our hotel among Narbonne’s narrow cobblestone streets. At the front desk, I asked for a dinner recommendation, and the concierge pointed us to Au Coq Hardi. The restaurant’s proprietor and I, in our imperfect mix of English and French, translated the menu choices to the rest of my family, and then the question turned to me. Cathi described for me a special dish called garbure, a thick stew of pork and chicken and vegetables, that wasn’t on that day’s menu. Her description was too good to turn down. And when she asked if I’d like it garnished, I figured a nice sprinkling of parsley and chives would be lovely.

The true meaning of her question was so much better.

In fact, garnie meant not a sprig of greens but an entire confit de canard — delicious, unctuous, melt-in-your-mouth duck leg. And when I was nearly finished with the broth, Cathi brought a small earthen cup of Corbières red wine.

“What the peasants like to do,” she said, “is pour it into the broth, then take up the bowl in both hands and drink it all down. Try it.”

From that moment on, I learned to say yes to the garnish.

Isabel had her first culinary epiphany a day or so later. I ordered a plate of escargot, then dared her to eat one. Eyes big, she thought long and hard before putting a snail into her mouth. But once she did: Mmm … Oh, yes. After that, hardly a meal passed her by without some snails in it.

It was fun to ask shopkeepers and restaurateurs where the wine, vegetables or meat came from. As often as not, they’d point out the back door. Before there were locavores, there was terroir. While our carbon-footprint-conscious millennials have created a sociopolitical movement out of eating food grown close to home, the French have always attached their personal and cultural identity to terroir. What does it mean? Basically just this: that the food and wine that comes from the earth right under our feet could not have come from any other place in the world.

And how. From market stalls to supermarkets, from farm stands to restaurant tables, from cassoulets to wine confitures, the experience of tasting our way through Languedoc is one that each of us will remember forever.

Engineering Made Easy

My dad was studying aeronautical engineering when he and my mom met in 1964. He loves solving boat problems, and he’s good at it. In our cruising years, the two of us got good at tackling projects together. I love every chance I get to deliver a boat with him, and this chance — to spend a week together in a boat without a delivery schedule — was one we hadn’t taken in 30 years.

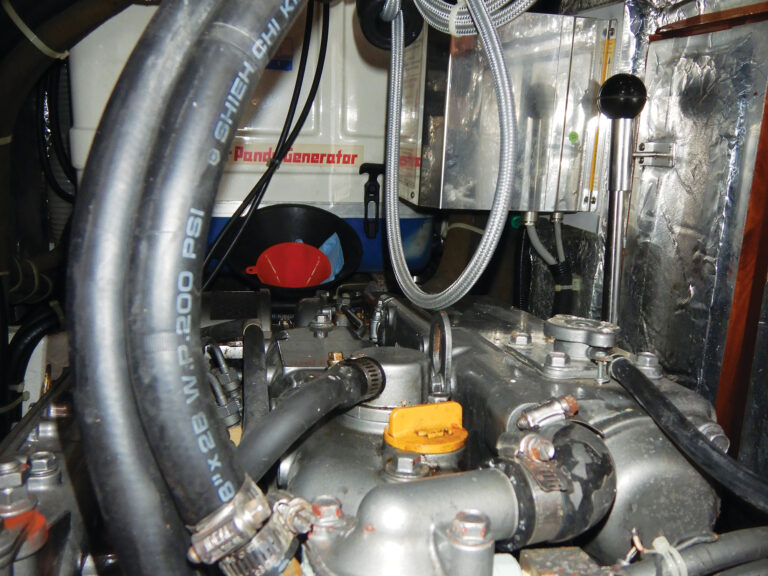

Running our chartered canal boat, a Vision4 SL from Le Boat, presented only simple problems. Nearly 50 feet long, the boat operates in two modes. The normal underway mode is with throttle and helm. This is as you would expect, except that the propeller is on an articulating pod, like an outboard-motor shaft mounted under the hull: When you turn the wheel, you actually change the direction of thrust. This simplifies maneuvering in tight quarters, and that’s even before the joystick comes into play. With the boat speed near zero, the helmsman can engage the joystick to control both the aft-mounted pod and the forward-mounted bow thruster. Push the joystick to the left, and the 50-foot boat walks to port. Twist the joystick to the right, and the boat pivots in its own length. At first we had to get used to an electronic delay. But once we did, maneuvering was easy, even in the locks.

Speed on the canal is stringently restricted to avoid eroding the shore. Le Boat enforces this restriction by installing a governor on the engines of all of its boats, keeping the cruising speed to a sedate 5 knots — just faster than walkers on the towpath, but not quite as fast as cyclists — a perfect speed to take in the surroundings.

Our weeklong itinerary from Homps to Castelnaudary took us uphill through 47 locks and nearly 330 feet of elevation. We quickly found that our schedules were set by the lockkeepers’ schedules: 0900 to 1230, then 1330 to 1800 (a bit longer from May through September). If you missed a lock before closing time, there was no advancing. On the plus side, it was easy to tie up anywhere along the bank and settle in for the night, secure in the knowledge that there would be no other traffic on the canal.

Only after several days of traversing the locks, watching the lockkeepers, and reading about the canal did we finally understand just what a brilliant solution Pierre-Paul Riquet had discovered. He certainly wasn’t the first to try a commercial canal through this country. A cursory look at a topographical map of Europe sets up the problem: Between the Massif Central mountains and the Pyrenees lies a relatively low plain — the so-called French isthmus — stretching from Narbonne to Bordeaux. And with the Garonne River leading into the Atlantic, all you needed to connect the two coasts was a navigable stretch from Toulouse to the Med. The Romans, who brought aqueducts to the region, imagined such a canal. Charlemagne tried. Leonardo da Vinci took a swing. But what no one could figure out was how to keep it full of water without silting.

Riquet was a hiker. He liked to take long walks in the Black Mountains above Carcassonne and Castelnaudary. It was there, in 1660, that he cracked the nut: find the highest point over which the Canal du Midi would have to pass, and then send water to that point from a reservoir higher still. Today you can visit each of those places: The Seuil de Naurouze, just west of Castelnaudary, is the canal’s high point, and all the water supplying the canal comes from the Bassin de Saint-Ferréol, up in the mountains. Of course, it still took 12,000 workers 15 years to actually create the canal. But Riquet’s eureka moment set it all in motion. Beginning with our first lock, at Jouarre, my dad and I enjoyed puzzling through the lock gates and sluices, identifying all the parts of the system through which we were traveling.

Even the plane trees and poplars that line the canal were Riquet’s idea: a lasting solution to the problems of erosion and silting. This final problem, silting, was the reason for the canal bridges. In earlier attempts, the engineers tried joining the canal with running rivers, but they became clogged with silt. Isolating the navigable canal from the rivers was the key, and the terraced design, stretching over 150 miles, allowed the canal builders to contain water from the mountain reservoir in a stone structure above the levels of other riverbeds. Spillways between locks ensure that the water depth within any stretch of the canal is precisely maintained.

Arts and Sciences

Of course, the French Midi isn’t all about science and engineering. It’s about art, too.

Jim Bricker is a painter, photographer and graphic designer — an artist with just the eye to appreciate the Midi landscape. At the end of one day, realizing we wouldn’t reach the lock at l’Aiguille before closing time, we tied up to the bank near the bridge at Puichéric a little on the early side. Straightaway, Rose, Jim and I hopped on our rented bikes and rode off into the vineyards.

In Languedoc, art is not so much in museums, but just is. Usually there aren’t signs; you have to know what you’re looking for. At Puichéric, I realized we were just a few miles away from a church I’d been looking for, Sainte-Marie de Rieux-Minervois. It’s said to have been designed and built by the Master of Cabestany, a 12th-century sculptor whose identity is unknown except through his works, which show up in Italy, France and Spain. For this church, the sculptor uniquely designed and crafted every marble capital on every column. Most interestingly, Rieux-Minervois is said to be the only seven-sided church in Europe — a place of medieval mysticism like no other.

After that excursion, we all rejoined each other back at the boat. We listened to a cuckoo across the canal, watched the light change on the bridge through the evening, and debated all the meanings of the word “romantic.” On my wall at home there now hangs an oil painting Jim created from that gorgeous day at the foot of the Minervois hills. When I look at it, I can still hear the cuckoo.

All along the canal, slow days were punctuated by splashes of surprising beauty. The walled city of Carcassonne, with its 51 towers and massive medieval ramparts, was almost overwhelming in its beauty. Red brick Toulouse was a vibrant university town worthy of several days’ exploration.

But to me, for sweet moments of a quieter sort, it would be hard to beat St. Sernin, a hamlet with a lockkeeper’s house and little else. Here, during the lunchtime pause, we pulled over to the canal bank, brought out bread baked that morning and olives, charcuterie and cheese from the farms around us, popped a bottle of Champagne, and clinked to the anniversary of the 50 years that brought us all here.

For more information on canal chartering, click here.

Tim Murphy is a Cruising World editor-at-large and an avid student of languages.