As the Sarah W. Vorwerk, a 53-foot steel sloop, snaked her way down the narrow Washington Channel, the helmsman averted his eyes from the rocky shore to the glowing iPad next to the wheel. Cape Iron appeared to starboard, the shoals of Punta Moraga to port. A tick to starboard got Sarah into six meters of water. We knew the Horn was just around the corner, but we couldn’t see it—except on the chart. Pinching to zoom out, we plotted our progress toward the ultimate objective, what they call down here el fin del mundo, the end of the world.

Eight seasoned sailors from the Bristol Yacht Club booked the Sarah for this trip-of-a-lifetime. Under captain Henk Boersma, the boat has made many roundings of the Cape, but none with an iPad aboard. This trendy tablet proved its usefulness on the voyage, not just for navigating, but also for many other tasks on board. With Apple selling several million a month, they have found their way into the hands of sailors all over the world, from cruisers to racers, from beginners to experts, from young digerati to old salts. How are they using this new device? Here’s a quick summary.

Navigate

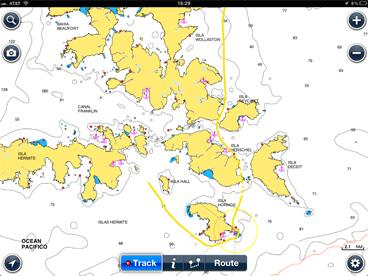

Through the Washington Channel between Isla Bayly and Isla Wollaston in the southernmost chunk of Chile, the iPad displayed the Navionics chart set of the Caribbean and South America. Captain Henk declared them more detailed than his own paper and electronic charts. They showed anchorages, land features, depths, distances, and hazards. They let us set waypoints and record the track of our progress on a 10-inch 1024-by-768-pixel display. At $600 for the iPad and $50 for the software and charts, the iPad compares favorably with dedicated chart plotters. We didn’t use the iNavX or GPS Motion X chart systems at the bottom of the world, but we use them all summer long at home. Of course we also carry paper charts, but our day-to-day navigation tool has shifted to the iPad. Its built-in GPS is quicker and its display bigger than most dedicated devices, and its pinch-to-zoom feature takes advantage of a natural gesture to scale in and out.

Alas, we had to take the iPad below when the rain started—with no resealable bag to protect it, we knew it wouldn’t survive the sprinkling. But even under Sarah‘s steel dodger, the tablet managed to get a signal and plot our course through the islands at the tip of South America. Many sailors have found the iPad to be a competent and useful support to their navigation.

Communicate

Although it could not compete with Sarah‘s SSB and VHF radio communication systems, the iPad nonetheless let us connect with the rest of the world during the rounding. We used strong WiFi and cell connections at Ushuaia, Argentina, and Puerto Williams, Chile, to read the New York Times and to send and receive email. We took snapshots and video clips of the ship, the sailors, and the voyage, and sent them home whenever we found a connection. One of the crew used Skype to call home from the iPad. While under way, we compiled our clips and edited them into a movie, right on the iPad (Check it out here). We wrote this article on the iPad. Each night, Sarah’s saloon was lit by the glow of the iPad as we reviewed the photographic record of the day’s journey. Had we a guitar on board, we could have even recorded sea chanteys.

Coordinate

The same iPad that navigated and communicated for us also managed many of the details of the trip: spreadsheets of flights and reservations and expenses; correspondence with lodgings, with Henk, and with the airlines; passport information (we found that you can use the iPad as a scanner to capture a photocopy of your passport before you give it up to the offices of the officials in Chile and Argentina who disappear with it into the back room.) We kept track of dates and times on the Calendar app, we jotted down key words into the Notes app, and we researched our travel arrangements with the Safari web browser app—all on the iPad.

Using much less power than a laptop, light in weight, and easy to pack, with a battery that lasts all day without recharging (which when necessary can be done directly from the 12-volt direct current on the boat), the iPad can serve as an organizer to coordinate the business and records connected with sailing.

Literate

Sailors read voraciously. Rounding the Horn, every crew member could be found peering into a novel or a history or a mystery. On the iPad, we carried a collection of Southern Ocean classics: Patrick O’Brian’s The Far Side of the World; Alan Villier’s Falmouth for Orders; William Stark’s The Last Time Around Cape Horn; John Kretchmer’s Cape Horn to Starboard; Charles Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle; and Dallas Murphy’s Rounding Cape Horn; not to mention the complete works of Melville and Conrad. All without adding an ounce to our sea-bags. And most of these titles came free from the iBookstore. A single iPad can contain a collection larger than most small-town libraries, and let readers enjoy the story day or night, without a light. No, it doesn’t smell like damp newsprint; but it’s small enough to snuggle up with in the cockpit or the berth. As a lightweight library for the literate sailor, the iPad can’t be beat.

The iPad wasn’t the only tablet on board—we carried a Motorola and an Android as well and found these very useful for many of the tasks described above. But none could duplicate the range of usefulness of the iPad, at sea or on shore.

Around the Horn, down the coast, or around the buoys, the iPad can help the sailor to navigate the course, communicate key ideas, coordinate the details of the trip, and ensure a literate voyage.

Capt. Jim Lengel stows an iPad aboard Top Cat, Alerion Express 38 yawl, which he races, cruises, and charters in New England from the Bristol Yacht Club in Rhode Island. He can be found at www.yawls.net