Best Boat Equipment

When we were preparing Osprey, our Adams 45 steel cutter, for full-time cruising and living aboard by a family of four, we did what so many other soon-to-be-cruisers do: We read and researched. And talked and listened. And read and researched some more. Though we’d been sailing all our lives, liveaboard cruising would be an entirely new thing for us. And while we had some pretty firm ideas about what we did and didn’t want, much of the new equipment and even some new systems on Osprey were more or less experiments, based more on how they’d worked for other boats and people than for us.

This is the leap of faith that, to one extent or another, we all must make, whether we’re placing that faith in our own judgment and capabilities or in those of an experienced boatyard staff or other pros. Sometimes it doesn’t work out. When that’s happened, we’ve had to suck it up, financially and emotionally, and find something that does work. (And it’s often far more than just a financial issue when something fails. It’s no fun to have one’s confidence shaken in one’s judgment, and it’s almost invariably a logistical challenge as well.)

Sometimes, though, things work really well, even better than we’d hoped. So we’ve come up with a list of the ideas and gear that have consistently proven themselves—both on passage and hanging out on the anchor—over the four years we’ve cruised aboard Osprey in the hopes that it might provide food for thought for those of you chewing over similar issues.

One caveat: These have worked for us, on our boat, in the places we’ve sailed. They might not work the same way for others. You still have to make the choices that seem best for your own boat and for the type of cruising you want to do.

Wind generators: Our pair of Eclectic Energy D400s, while complicated and expensive to install, have been worth every penny. We’re happiest on those windy days at anchor, since they work best when we have winds of at least 15 knots, even better with a little more. Their production falls off sharply at low wind speeds. What we love most about them—and what constantly draws other cruisers to ask questions—is how quietly they operate. Even in 20 knots of wind, we barely notice them. Interestingly, when we first came out here, we rarely saw D400s, and then mostly on European boats. Now we’re seeing them everywhere, and on more American boats.

Solar panels: Our four panels—two Shell 85s and two Kyocera 135s—and the controller have worked extremely well. The only thing we’d change would be to add more of them, and to build movable brackets so that the panels—ours are presently fixed in place—can be angled to capture more sun throughout the day. When we were prepping for cruising, a good friend who’d been out already for two years recommended a combination of wind and solar power. We listened, and we’re passing on the advice here. Many times we’ve been under way or at anchor on cloudy but windy days or on windless but sunny days and still able to make plenty of juice in either situation, while friends with only solar or only wind power—or, worse still, neither at all—had to resort to a genset or the main engine to keep their batteries up.

A single-sideband radio, Pactor modem, and SailMail: While some may pooh-pooh this gear as sunset technology, we wouldn’t go without it. It takes a bit of attitude adjustment to go from iPads and hot-and-cold running Internet to working with the SSB, but its value is its dependability, no matter where you are. In Panama’s Kuna Yala, for instance, our cruising would’ve been tethered to the sole island that had Internet (three hard lines run off a solar panel, at the equivalent of $3 per hour) had we not been able to remain in contact with friends and family and access our Gmail account via SailMail through the SSB. True, a new SSB will set you back at least $1,500 initially, with another grand or so for a Pactor modem. Once they’re installed, though, a $250 annual SailMail account gets you email, weather GRIBs, and weatherfaxes, and you’re immediately linked to the SSB community, an intangible but real benefit you can never enjoy with a satphone.

Harken sailhandling equipment: Osprey is completely Harken, with the exception of two snatch blocks and her original Australian-built Barlow winches. Even if her deck hardware hadn’t been in dubious shape when we bought her, we would’ve replaced it with race-ready Harken gear. It’s been our experience that no matter the boat, when it comes to sailhandling, speed and efficiency equals safety. And the easier it is to sail the boat, the more you’ll actually do just that: sail. Our adjustable genoa leads, mainsheet system, main-halyard system, and turning-block system have worked flawlessly in this harsh, difficult environment and have proven their worth time and time again by enabling us to quickly and easily adjust the sail plan according to conditions.

A four-stroke outboard: Ours is a four-stroke Yamaha 15. It’s been

extremely dependable, easy to fix when necessary, and easy to find parts for, even in such places as Guatemala and Panama. Fuel-efficiency, though, is where it really shines. Many of our friends run 6-gallon tanks on their two-strokes, with mixed oil and gas. We run a 3-gallon tank with straight gas and fill up half as much as they do. When you’re relying on the dinghy to be your car, and gas costs the equivalent of $6 a gallon or more, this fuel savings adds up in a hurry. And it’s environmentally better in every way.

The biggest rigid-bottom inflatable dinghy we could manage: This was another recommendation from a well-seasoned cruising friend, and rarely a day goes by when we don’t thank him for it. Osprey doesn’t have davits, so we were limited by what would fit overturned on the foredeck while on passage (which we happen to believe is the safest way to carry a dinghy offshore). We have a 10-foot Caribe. Coupled with the Yamaha 15, it’s been a real workhorse for our family of four, letting us plane easily, even loaded with groceries or dive gear, and keeping us mostly dry in sometimes pretty snotty conditions. We can’t tell you how many friends we’ve watched get drenched and pounded trying to get groceries or do laundry because they went with the smallest or cheapest dinghy they could get away with. We also recommend covering the dinghy with a good set of canvas chaps. They reduce wear and tear and the brutal effects of the sun.

A Cape Horn Extreme watermaker from Spectra: This was also an expensive and complicated system to install on Osprey. But like the wind generators, it’s worked extremely well overall and made our lives, especially in remote places, much easier. We’ve had friends without watermakers who’ve had to limit their cruising because they were worried about the unavailability of safe water or the need to beg it constantly from people who could make their own. True, you can always hope for rain. But we’ve been in places where it hasn’t rained for four months. Our experience has been that the watermaker has broadened our cruising capability. The Cape Horn Extreme is mechanically the simplest of Spectra’s products (i.e., no circuit boards), and we recommend it because there’s less to break and go wrong. Spectra has proven to be an excellent company with which to work. When our Clark pump broke unexpectedly in the Bahamas last winter, a replacement pump arrived there within five days at ultimately no charge, except shipping.

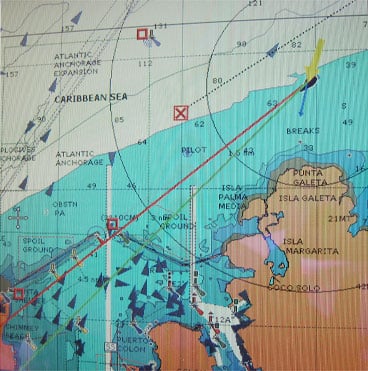

An AIS transponder: We began our trip carrying only an automatic

identification system receiver, feeling that we didn’t really need a transponder; they were also a lot more expensive then. But two years ago, we installed a transponder, and it’s proven its worth repeatedly, particularly in areas with a lot of shipping but not always a lot of decipherable English spoken from the bridge deck. Imagine being among five ships offshore in the dark with CPAs of less than a mile and a half converging; one of the ships is the largest cruise liner in the world. That ship ended up calling us because they could see us easily via the transponder. Many times we’ve asked ships if they had us on radar and they said no, but they did see our AIS signature. We’re a small boat on a big ocean. Any device that makes us more visible and helps remove the guesswork in busy situations is a no-brainer.

Aries windvane self-steering: This system hung on Osprey‘s transom for two years before we used it on a 1,200-mile passage across the Caribbean. Now we use it whenever we can. In the right conditions, it becomes our primary offshore steering, quietly and efficiently tracking us along and costing us not a single amp. And it’s a backup for the electric autopilot if that system fails or we have some battery problem that prevents us from using it. We’d discourage people from ditching an installed wind-steering system to make room for, say, dinghy davits. We know one couple who, as a wise precaution, reinstalled their windvane before sailing from the Bahamas to Puerto Rico. Two days out, they lost their electric autopilot. Had they not reinstalled their windvane self-steering system, they’d have been hand steering for days.

A Reverso fuel-polishing system: Most people associate fuel-polishing systems with large motoryachts, but they make eminent sense for cruising sailboats that travel long distances to remote places. Osprey carries approximately 195 gallons of diesel in two tanks. That’s a lot of fuel that more often than not just sits there—we are, after all, a sailboat—having ample time and opportunity to grow stuff. Also, some of the places we’ve purchased fuel have been dubious at best. In one memorable establishment, a fellow poured diesel from a 55-gallon drum into a 5-gallon bucket through a T-shirt filter while it was raining. The fuel polisher is independent of the fuel lines for the engine. It draws from the very bottom of the tank and returns to the very top. Running it about once a month, three to four hours per tank, keeps the fuel clear and free of water and growth. The proof’s been in the pudding: Several times we’ve set out to replace the Racor fuel filters but have simply reinstalled them because they’re so clean. As an added bonus, when one tank is getting low, we can use the system to move fuel to the opposite tank and keep the boat in trim. And more than once we’ve been able to help fellow cruisers polish their contaminated fuel. It wasn’t a particularly easy or cheap system to install, but it draws little power when it’s working, and it’s been worth its weight in diesel.

We also boosted Reverso’s income by purchasing its oil-changing system. This fairly simple device has a hose connected to the bottom of the oil pan. A reversible pump sucks the oil from the pan and through a hose into a container of your choice. After wiping the discharge hose off, you can use it as the suction hose and install the new oil right back into the engine. It takes about 10 minutes to change 6 quarts of oil in Osprey‘s engine, and other than the unavoidable mess of changing the filter, the whole process is clean, quick, and easy. Anything that makes such a vital but potentially sloppy bit of routine maintenance easier is worth it, and this system keeps everything nasty contained and out of the bilge.

A Honda EU20i portable suitcase generator: One of the first items we bought was this tough, compact unit. It’s proven invaluable when we’ve had periods of windless, cloudy days and our solar panels and wind generators aren’t putting out much. The Honda is far more efficient at recharging the batteries than the boat’s main engine and alternator (and this also saves wear and tear on the main engine, since running it “unloaded” is tough on a diesel). On eco-throttle, which is its conservation mode, the unit will run for almost eight hours on a single fill-up of less than a gallon of gas. We also use it for projects that involve a lot of electricity, like drilling, grinding, and sanding, rather than drawing off the boat’s batteries and inverter.

The Clarke family is currently aboard Osprey in Annapolis, Maryland.