If you’re considering purchasing or chartering a catamaran, fret not about maneuvering. While a lack of keel(s), high freeboard, and the vessel’s light weight might seem daunting, the dual engines and twin-propeller configuration are powerful tools, even when space gets tight and wind and current present extra challenges. With judicious use of the throttles and a crew well trained in handling spring lines and fenders, maneuvering a cat in close quarters can be easy and efficient.

For beginners, the first trick is learning to forget the wheel and leave the rudders in a neutral position, at least initially. There’ll come a time when the rudders will be helpful, but save that until you’ve gathered enough experience. Because a cat’s twin propellers are so far apart, it’s simply not all that necessary to use the rudders; in fact, for skippers learning to drive cats, rudders may introduce an unnecessary dynamic.

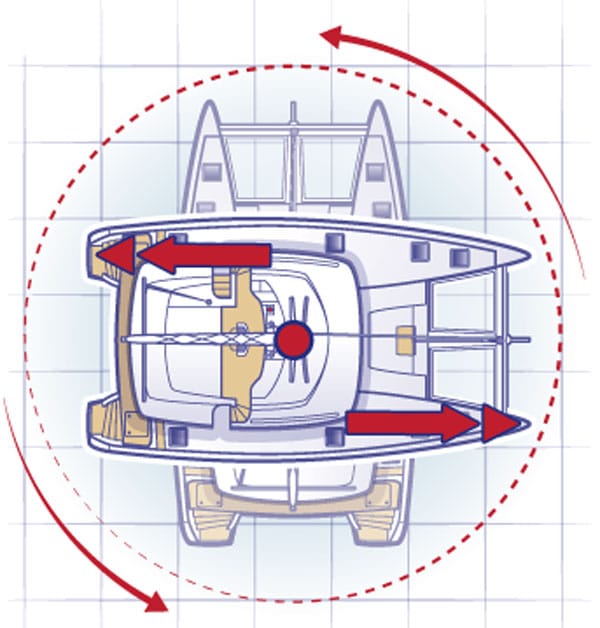

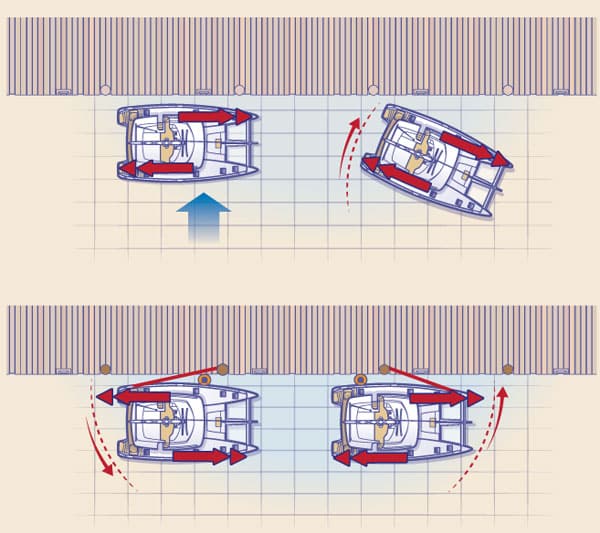

The main principle one must grasp is that a cat can pivot, without moving forward or aft, in its own length. By advancing one throttle and reversing the other in equal measure, a cat will simply rotate on its centerline axis. When you apply greater and lesser power to the respective throttles, you will pivot from the side to which you’ve applied less power. For example, to pivot to port, use slightly less reverse power to your port engine, and slightly more forward power to your starboard engine. To pivot to starboard, do the opposite. Also, a cat can be operated at very slow speeds because you don’t need to create a flow over the rudders in order to turn. When it comes to cats, “Slow is pro.”

Remember that it’s usually best to reverse into a slip rather than come in bow first. This keeps the skipper nearer to the action and provides the opportunity, if things start going sideways, to simply power forward out of trouble.

Start slowly. Have an experienced cat driver take you off the dock for your first few departures, then pick a wide-open area in which to practice basic maneuvering. Use mooring balls (they’re softer than pilings or navigational marks) as aiming points, and start practicing. Learn to back onto the mooring, come alongside it, and pick it up; soon you’ll see how easy it is to accomplish these basic tasks. The more you practice, the higher your confidence level will soar. Once you’ve got the basics down, start performing those same exercises in wind and current to see how windage and sideslip affect your particular boat.

Next, try some basic docking maneuvers, starting with coming alongside or departing from a fuel dock. You’ll discover how a properly placed spring line and fenders, combined with careful use of the throttles, can bring you neatly alongside, even on a crowded dock. Now practice backing into a slip. While most cat drivers prefer, and some narrow dock spaces demand, that cats occupy the “face dock” at the end of a pier, there will be many marinas that have enough room to allow your beamy vessel to fit neatly into a slip.

Once these skills are mastered, try picking up a mooring and dropping the anchor. These maneuvers depend more on the crew than the driver. That’s because mooring and anchoring can be different on cats; the crew doesn’t stand at a pulpit but perches on a crossbeam, and from there may have to reach a long way for a mooring ball or deal with an anchor that’s mounted well aft of the bow. Here are some additional cat-handling tips for specific situations.

Docking Ins and Outs

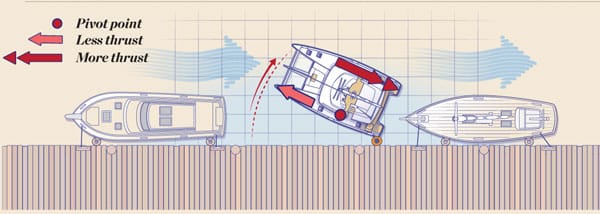

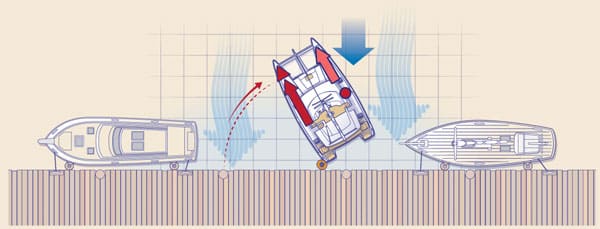

Let’s say you’re approaching a dock to come portside to. Your first line ashore will be a spring that leads forward from your port quarter. Once you’re near the dock, put the port engine in slow reverse and the starboard engine in forward with slightly more throttle applied. This will place the boat close to the dock, and once the spring line is secured and tightened, it will hold you close and steady (with your engines still turning slightly) and allow you then to secure the bow and stern lines and the aft-leading spring lines.

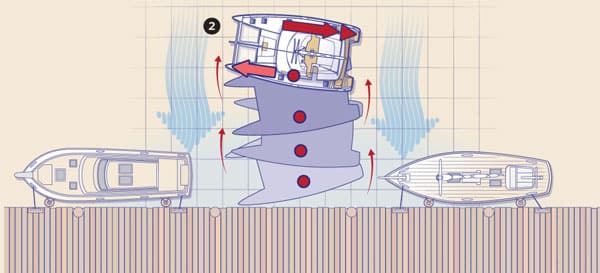

Leaving a dock, use the same principles; apply them perhaps a little more aggressively if boats are parked forward and aft. Tied starboard to, first, place a fender or fenders as far aft on the starboard hull as possible. As the dock lines are cast off, apply more power in reverse to the port engine and less in forward on the starboard engine. This pivots the bows out; once they’re both well clear of the boat ahead, simply transition the port throttle into forward and drive away.

Backing into a Slip

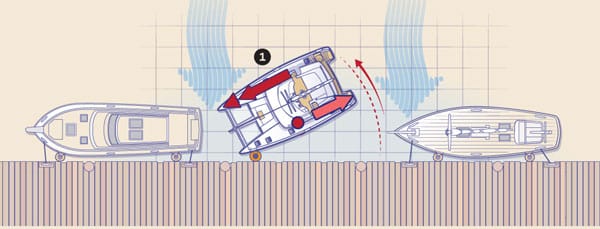

As I said, I’m firmly convinced that backing a cat (or any other vessel, for that matter) into a slip is preferable to bringing it in bow first. On most cats, the steering station is centered or slightly aft, which translates into better visibility to the sides and behind you. It’s important to know how close your sterns are to the dock. It also gives you much better maneuverability and options when bailing out from a maneuver gone wrong: Instead of wrangling with which way to turn when making your escape—when reversing, many sailors have to think a little harder about which throttle to use to turn in the proper direction—you simply drive straight ahead, then decide which way to spin the boat.

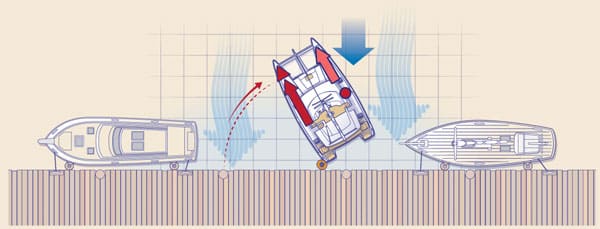

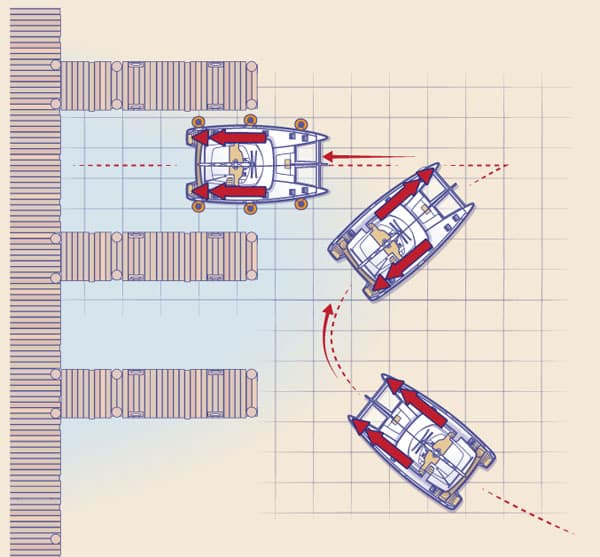

In tight quarters, you can approach the slip in forward, then do a K-turn to position the sterns so they’re aiming at the slip with the cat parallel to the docks on either side. Apply reverse thrust on both engines to pull straight back. If necessary, you can apply forward throttle to either hull, as needed, to straighten the boat out as you’re entering the slip.

If there’s not a lot of space in the marina, you may want to enter the area already in reverse, then simply maneuver the sterns into the slip using the same principles described above.

Picking Up a Mooring

Cats sit best on moorings when the boats are equipped with a bridle rigged between the bows, the apex of which should be equidistant between the hulls. When the cat approaches the mooring ball, your crew should stand by equipped with a long boathook and with the bridle ready. As with any boat, a slow approach from as far downwind of the mooring as possible is ideal. Have a signaling system in place so the crew can tell you the distance from the mooring and whether you need to steer to port or starboard to line it up properly. Hand signals are best, and everyone should be on the same page so there’s no confusion. Again, slow speed is optimum, and you should be ready to stop forward motion quickly.

As with any boathandling technique, practice makes perfect. You won’t always dock or moor in benign conditions; once you have the basics down, keep practicing in more wind and current so you’re always familiar with how your boat behaves. A comfortable skipper is a calm and assured one.

Tony Bessinger is an instructor at Confident Captain/Ocean Pros in Newport, Rhode Island, and has thousands of miles of catamaran sailing experience, including a stint as a skipper of a Gunboat 62, and a 4,600-nautical-mile delivery of a Leopard 46 from Florida to California. He also drives high-speed ferry cats in southern New England.