Sea of Lost Dreams Cover

_Penniless and hunted, Captain Dugger and his lover, Kate, along with first mate Nello, make a spectacular moonlit jailbreak in 1921 on Mexico’s El Día de los Muertos and set sail for the South Seas. But they soon fall prey to the intrigue of two mysterious stowaways: Darina, a young Irish escapee from the brutal Magdalene nuns who’s in search of her lost twin, and Guillaume, a seasoned French spy sent to kill the leader of an anticolonial uprising.

Set in the fiercely beautiful volcanic islands of French Polynesia, this second novel in the Dugger/Nello historical adventure series is the story of man against the fury of the elements, of dreams colliding with reality, and of an anguished culture combating tyranny. Below, we catch up with Dugger and the crew in mid-Pacific as a tempest descends. —__The Editors_

————————–

The storm closed in. They tried to escape with all sails flying, but by early evening they’d been caught by the low black clouds, swirling like molten lead, fusing with the darkness. As the wind grew, they reduced sail, piece by piece, dousing the mizzen staysail, then replacing the yankee with a jib half its size, but the ketch still yawed wildly as she sailed down twisting slopes. They dropped the mizzen.

With his shoulder strong again, Dugger took extra turns at the helm, tirelessly fighting the rising wind and seas. He feared the steepening waves but relished the exhilarating power of the ketch. Cleating the empty mizzen halyard, he glanced at the sea behind them. There were only waves and clouds—the albatross wasn’t there. His heart sank, but then he thought, Would you be here if you didn’t have to be?

Night fell without the soothing lull of dusk. The light vanished suddenly from the sky, leaving only the suffocating dark and the hiss of breaking seas. Now and then a pale smear flared up in the gloom as a wave convulsed into churning pools of foam.

Dugger steered the ketch, with Kate close beside him. He followed no compass course, steering only by the angle of the wind that blasted across the deck, pressing on in the doomed attempt to outrun the storm. Belowdecks, the others were wedged into their berths, Guillaume trying to read, Nello staring at the deck beams near his face, and Darina watching the gimbaled lantern steady on the bulkhead while the ketch rolled and heaved.

Then the first gust hit.

An atrocious blast of wind knocked the ketch onto her rails and covered her with flying sheets of water. She lay with port deck under in the stunning darkness, but even half submerged, she persevered and sailed.

Dugger and Kate fell into a cockpit corner, but with an iron grip he held on to the wheel. The ketch righted herself, shedding the sea in streams. Dugger clutched Kate, but the feel of her wasn’t enough; he had to hear her voice. “Are you all right?” he shouted, but the wind and crashing seas blew his words apart.

“Yes!” Kate shouted. “Fine! Really!”

The main hatch flew back, and a glow shot into the sky. “Cappy! Kate!” Nello roared. “You still there?”

He burst out of the hatch, the storm lantern in hand, his face strained with worry. He hooked the lantern onto a boom bail where, swinging, it lit the vaporous air and their faces.

“Storm trysail!” Dugger shouted, and Nello crept toward the mast. Dugger slid Kate’s hands onto the spokes of the wheel. “Steer 100 degrees! Then when I wave like this”—and he swung his arm back and forth as if shooing away a fly—“head up to 200 so we can drop the main! Understand?”

Kate repeated his instructions: “One hundred. Two hundred.”

Dugger took the doubled mainsheet, wrapped it around her waist, and knotted it. “In case you decide on a swim!” he shouted. With his knees braced against the cabin, he inched forward to the mast to uncleat the halyard and wrestle down the main. Another gust hit, and through the trembling light, streams of brine flew at him like hail.

Just wind and water, he thought, but a bit too much of both.

The halyard wouldn’t give. The salt spray had soaked the hemp, each tug of the sails had pulled the knot tighter around the cleat, and the sun had baked the salt hard in the braiding, so he had to use the marlinspike to loosen it.

Kate put all her weight against the wheel, clutching the spokes, repeating, “One hundred. Two hundred.”

Nello had the lash-downs ready, and Dugger finished prying open the knot. Holding the halyard in one hand, he waved the other toward Kate. But with her eyes filled with brine, Kate didn’t move. “Two hundred!” Dugger bellowed. “Two hundred!”

The next gust hit, and the ketch went on her side into the churning sea. She struggled to right herself, but the gusts detonated one behind the other. A wave burst over Kate and forced her to her knees, but she clung to the spokes, gasping in the foamy air.

The wave smashed Nello into the sail, his face into the canvas, and he swore if they made land alive, he’d never look at the goddamn sea again.

Dugger slid overboard. He’d been standing beside the mainmast and waving to Kate to head the bow into the wind when suddenly the ketch went over. He grabbed the rigging, but a surge of water lifted him and swept him into the sea. The wind drove the ketch into him, and all he could do was hold his breath and wait. The sails were above him, so he knew the ketch hadn’t gone turtle but just lay on her side, and with the keel levering her, she was bound to right. Sooner or later.

Down below, Darina and Guillaume were hurled across the saloon. The world turned on its side, the bulkhead lamp went out, and they crashed into each other. They lay next to the port light that was now buried in the sea.

In a lull, the drowned ketch began lethargically to rise. She came up slowly, held down by the water in her sails, and the weight, as she righted, began to tear the seams. Stitching parted and distended panels burst. The ketch stood upright and dumped Dugger on deck. The clouds cleaved, the moon shone down, and the torn slabs of canvas fluttered like great laundry.

Nello helped Kate up, and turned the wheel. Dugger knelt on the foredeck and with resolute calmness wrapped the sheets around the jib and staysail, then tied them to the lifelines to keep them from flying overboard. Then he uncleated the mainsail halyard to drop the main, but it wouldn’t fall. Its lower panels rippled freely, but an upper panel, still one with the bolt rope, had wrapped itself around a shroud and held the halyard tight.

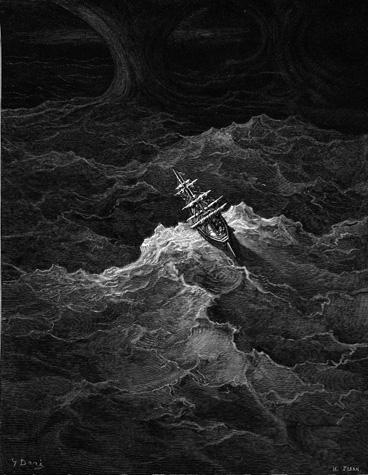

Illustration by Gustave Doré

“It’s stuck!” Dugger shouted, yanking at the rope to show Nello. “I need the bosun’s chair!”

Nello came forward through the buffeting wind.

“I have to go up and free it!” Dugger yelled, his voice shaking with worry. “Or we’ll lose it!”

“So we lose it!”

“And sail with what? If we can save the pieces—.”

“We have a storm sail!”

“The size of a handkerchief! It’ll take us a year to reach Tahiti!”

“It’ll take you longer if you drown!”

“How can I drown? I’ll be tied in! For Chrissake, get the chair!”

Nello considered ignoring him, but Dugger’s face remained unrelenting. He headed below to find the chair.

“Get Guillaume to tail!” he heard Dugger call.

The ketch slid down a wave and rolled from side to side, the masts drawing fierce arcs across the ragged clouds.

Guillaume tailed the jib halyard as Nello cranked the winch. Dugger, his feet dangling from the narrow plank of the bosun’s chair, his hands clutching its canvas sides, was pulled slowly up the mast. Don’t look down, he told himself. You’re tied in; you can’t fall. And if you do, what the hell? With the ketch rolling, you’ll be pitched overboard. It’s only water.

With no sails to dampen the roll, the masts swung like a metronome. He was thrown against the shrouds on one side, then flung through the air into the shrouds on the other. Dugger grabbed at the halyard with both hands. Tatters of the sail thrashed him like bullwhips, and the rain slashed through the moonlight in silver streaks.

He was past the spreaders. From up so high, the ketch seemed in another world, struggling in huge seas besieging her from every side. The lantern’s yellow glow wandered in confused circles, now lighting the flooded cockpit, now the tangled ropes near the mast.

Darina had come up and gripped the mizzen shrouds. This is no Inishturk storm, she thought. There, you stood on solid granite. This is the violence of heaven sent to destroy the ketch. And crew. Who can it be after but me? Me. The sisters warned you there was no escape. You can escape the Magdalenes, but heaven will always find you. She closed her eyes and clasped her hands and prayed. Forgive me Father, your worst sinner. Mea culpa, mea culpa. I deserve all your wrath. But please, Lord Father, let them live.

Kate steered. She could barely make out Dugger near the top of the mast, and she mumbled, “Dear God, bring him down safely.” As the mast swung, he flew from starboard, kicked the headstay, and, 40 feet above the deck, was pitched toward the mast. He hit hard but hung on. The rain poured down his face, into his eyes, but he began to unwrap the sail. Calmly, Cappy, he told himself. Don’t yank or tug, or you’ll just make it tighter. It’s just a piece of canvas. An old lady could do this. Like untying a shawl. His heart was pounding, and he had to force a breath. He unwound the tangled canvas from the shroud, then rolled it up and knotted it so it wouldn’t tangle again.

Nello roared, “Well done, Cappy!” and Guillaume shouted, too, and Kate was so thrilled that for a second she closed her eyes. A wave caught the rudder and the ketch spun to port. The next wave knocked her down.

Guillaume was thrown against a stanchion. He lost his grip on the halyard he’d been tailing, and it fed quickly out over the winch. With the halyard now free, the bosun’s chair was loose. Dugger fell. The fierce swing of the ketch catapulted him away from the mast, out over the waves. He plunged in a deadfall with the rope trailing behind and vanished in the abyss of wild seas.

He surfaced. The seas loomed like cliffs around him. Far up among them, the lantern glowed, then grew faltering and faint, until it vanished in the darkness.

Dugger floated on his back and tried to catch his breath. Breaking crests and dangling clouds loomed over him. A wave lifted him, and his hopes rose too that from the top of the wave he might see the ketch, already turned, coming in the moonlight, but once on the crest, he glanced around and saw only foaming seas.

He made a brief attempt at swimming, but his bad shoulder ached when he raised his arm. Besides, he was unsure of the direction, so he stopped. His head hit something hard—it was a piece of wood, the seat of the bosun’s chair. With the halyard still attached, trailing behind. He clutched it. The sound of rushing seas came at him through the dark, passed by, then crashed, as if on unseen reefs. Once in a while there was silence; the wind dropped, the seas fell, and the world became so peaceful he thought the storm could not return.

Then it did.

A savage gust churned the sea. He closed his eyes and tried to forget where he was. He let his head fall back into the sea. Think of something else, he told himself, something good. In the darkness behind his lids, Kate’s face came alive. She looked sad, holding back tears.

He felt immeasurable warmth flowing from her; from her arms that clutched him in need, or in passion; from her mouth that clamped over his with urgency; from her whisper, “This is another world.”

A black wave broke over him; he swallowed water and coughed. He kept his eyes shut and summoned more visions—one at a time—always close enough to touch. Why her? After so many years, so many women, why suddenly her? Maybe because she loved with such fervor, as if there were only that moment, murmuring, “I never imagined life could be so exciting.”

He shook his head. If these are your last hours, he thought, at least put up a fight. He took a deep breath and began swimming. I’m not dying until I see her again. If they can’t find me, I’ll find them. Or land. It can be done. Remember the Burmese who fell overboard off West Africa 100 miles from land, and all he did was follow the rising sun, swimming no more than maybe 15 miles a day—drank rain, even caught a fish that came close out of curiosity. He knew that as long as he kept on, endured, and sang—yes, that was a big thing, wasn’t it? He sang, sea songs and folk songs, even lullabies his mother used to sing. Over and over, songs without a break, for hours on end. He sang and swam for six days; the ship’s log bore him witness. By then he had no strength for singing, not even humming, but he kept thinking the songs. And on the evening of the sixth day, he heard a song. A new song. And he saw, with swollen eyes, a sand spit of the shore. His eyes were much too dry for even a single tear.

So Dugger swam. The clouds were riddled with moonlight. He marked that as east and swam. He sang a song about an aging highwayman, his hair turning like winter’s early frost, his face lined by love and loss and laughter, but even though his eyes still blazed bright, the young and fickle women no longer looked his way. The tune was melancholy, and he swam slowly, crawling up the waves and sliding like a child in a sled down their shiny backs. Fifteen miles a day, he thought, and one day you’ll reach the coast of Chile or Peru. He wasn’t sure which, but he was sure of the distance. He’d be there by Easter.

“‘And those fickle women never even look my way.’”

He swam with his eyes closed and saw Kate in the shadows of that long-ago moonlit night, only the white of her breasts and her eyes, and he felt her flesh against his mouth, then tasted the sweet damp of her thighs and heard her gentle voice and his head filled with her fragrance of a jungle flower and smoke. And he felt his head in her caress.

Then later, when they were wound around each other, he whispered, “I love your taste.”

“You can taste me forever,” she whispered back. After a long while she said, sighing, “I wish time would stop.”

And he remembered feeling a great calm and thinking, This is where life begins. She kissed away a tear from the corner of his eye and whispered, “You will always have my love.”

He swam until his arms shook from exhaustion. He lay, out of breath, in the storm-torn sea. “I’m sorry,” he murmured, “I would have died for you.” It’s such a waste to die saving a torn sail. But maybe it will help. Maybe Nello can pull the sail down now, and when the storm ends and the sun is warm again, you can sit in the shade of the awning with needle and sailmaker’s palm and sew up the pieces. And maybe you can sing to pass the time; a good song, a cheery song—any song but “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean,” because by then, your Bonnie might be miles under the sea.

He swam.

Ferenc Máté (www.ferencmate.com) is the author of 15 books (available at www.amazon.com), including Ghost Sea, the first in the Dugger series.