Wings of Grace 368

It couldn’t have been a more Maine morning. Lobster boats and Friendship sloops hung in docile array from their moorings, their reflections aflutter in the not-quite-still, cool waters of Southwest Harbor. Gulls bickered overhead, and aboard Leslie and Michael Rindler’s 50-foot ketch, Wings of Grace, the scent of fresh-baked muffins wafted up from the galley. No store-bought muffins these, they were handcrafted that morning by Leslie and loaded to the crowns with first-of-the-season wild Maine blueberries. All that was missing was the fog. Not for long, for as we motored Wings of Grace toward Cranberry Island, the familiar gray cocoon enveloped us.

At the U.S. Sailboat Show in Annapolis in October 2006, her black hull and varnished cabin trunk had set Wings of Grace distinctly apart. A brutal nor’easter pummeled the Chesapeake Bay for most of the show, flooding the docks for hours and limiting to a few minutes on the last day the time I could spend aboard. In that season of migrations and tight schedules, there was no time to sail her before she departed for her winter quarters near Charleston, South Carolina.

Fortune finally smiled, and last August I found myself aboard Wings of Grace in the company of her owners and builder, Todd French, of French & Webb, for the run from Southwest Harbor to Belfast, where French’s crew was to prep her for display in the show organized by Maine Boats, Homes, & Harbors magazine. Wings of Grace is a sublime exhibit for that event: Designed in Maine by Chuck Paine, she was built in one of Maine’s iconic harbors, and she serves as the winter home for the Rindlers, who summer in Maine.

A dose of fog will bring out the mettle of any mariner, and Michael Rindler was ready to take it on, the pages of his chart book tagged with sequentially numbered sticky notes and a chart plotter with radar overlay under the dodger. He threaded Wings of Grace between rocks, islands, and traffic, and he politely deferred all my writer’s questions to Leslie until we were clear of the complications of Casco Passage and the fog had dispersed ahead of the building sea breeze.

Wings of Grace trundled along at a brisk pace, powered by her 92-horsepower Yanmar diesel, while we admired glimpses of lobster boats, ferries, and a typical Maine assortment of pleasure craft, many of them, like Wings of Grace, built of wood and looking for wind to fill their sails.

Even when, as we approached Eggemoggin Reach, the fog yielded to the sun’s force, the wind was slow to take its place. Still, with the visibility good, the conversation turned from guessing what the red radar blobs overlaid on the chart plotter might portend-schooner or skiff?-to, well, other things Maine.

Todd French pointed to an elegant, low-slung mansion to our north, on a bluff overlooking a sheltered bay where a cluster of vessels clung to moorings. “That’s the WoodenBoat spread,” he said.

“As in the magazine?” I asked.

“Yes. The offices are in the house, and the school is just down the hill. That’s the boathouse, by the mooring field.”

I was reconsidering the wisdom of having moved south from Rhode Island instead of north, where editors can claim offices with such vistas, when Michael Rindler spoke up.

“I’m taking the marine-photography course there in September,” he said. As if to emphasize the point, he aimed his rather intimidating-looking Leica at me. “I’ll bring Wings of Grace here to live on, and I’ll row in to class every morning.”

In the space of a couple of hours aboard, I was beginning to get a feel for the Rindler lifestyle. Early in the trip, Todd had mentioned cars, and Michael admitted to having a small collection. A recent addition was a BMW 2002, the classic that put BMW into the consciousness of the American car buff.

At some point, I noticed the boat’s steering wheel. (Nobody else was paying it much attention because the autopilot was supplying the muscle.)

“It’s modeled after the banjo wheel on the 1952 Porsche,” volunteered Leslie. “We loved the wheel on that car, so we had the guys make the boat’s wheel to look like it.” The three stainless-steel spokes, each made up of eight polished rods, juxtaposed with the six-sided glass compass cover, are a handsome reminder that no government agency has yet required airbags and other clutter to interfere with the elegance, or whimsy, of a ship’s wheel.

Michael and Leslie trace their sailing days back to high school, when Michael owned a 16-foot X-class dinghy. When they were dating, they sailed it on Lake Geneva, Wisconsin.

“It would sink every week, right up till the deck was just showing,” said Michael, “and on the weekend we’d bail it out and go sailing. It never really tightened up.”

Their next boat was a Melges M16 scow, but they weren’t into racing; they just liked being on the water under sail. From that they progressed to a Rhodes 19, then to a Bud McIntosh 24-foot wooden double-ender.

In the late 1990s, they dallied with fiberglass, first aboard a Hinckley Bermuda 40, then on a Hinckley Sou’wester 42 on which they took a sabbatical year, sailing to the Caribbean and back.

They made the cruise so that they could take their son, Timothy, then 11, to give him a taste of the cruising life and of the world while they home-schooled him through sixth grade. On the way south, they meandered along the coast from Maine, reaching Norfolk, Virginia, in October. From there they sailed to Bermuda, then ultimately as far south as Grenada.

After that, it was back to work, back to school, and back to terra firma until Timothy was off to college and they could replace the winter home in Hilton Head with one sporting sails.

While the Rindlers had a pretty good sense of what they needed in their new boat, pinning down the overall look proved more difficult. Then, at the Maine Boatbuilders Show in 2002, they saw the components French & Webb had built for the Alden schooner Lion’s Whelp, then under construction at Portland Yacht Services. Impressed, Michael chatted about his desires with Todd French. After the show, French sent him a copy of the coffee-table book of John Alden’s designs to study. A little later, Michael took the book to Chuck Paine, opened it at the page he’d marked with a yellow sticky note and said, “I’d like a boat that looks like that.”

The design he’d marked was a Malabar schooner. What he ended up with was a lovely boat that looks like the Malabar right down to the black-painted hull but ketch rigged. She even has the full-length keel but with Paine’s oversized aperture in the trailing edge, which permits the rudder to be balanced. Paine describes the rudder as being essentially a spade but with a structural gudgeon at the bottom; being balanced, it eliminates the heavy helm normally associated with full-keel designs. The arrangement also gives the propeller lots of clear water to work with even while protected by the keel, and it seems especially well suited to Maine’s lobster pot-strewn waters.

Paine allows as how his relationship with Michael Rindler is well up on the positive end of the scale. “He knew what he wanted,” Paine says, and that can certainly make a project run more smoothly for the designer-not that there weren’t a few wrinkles. “He wanted to keep the boat small, and it started out at 48 feet, but we were really having some problems, especially fitting in the aft cabin, where cabin-sole space was getting tight.” So Wings of Grace ended up at 50 feet, and because a little extra length never hurts a yacht’s profile, she likely came out even better for it.

Before Paine hit the “save” button on the arrangement plan, French & Webb built a mockup of the interior so the Rindlers could walk around and see how everything worked in three dimensions. The only major adjustment this triggered was the sacrifice of a quarter berth proposed for the aft stateroom to give the generator a space where it was accessible and could breathe.

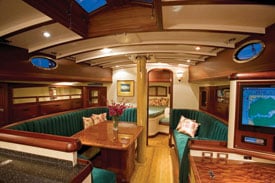

Billy Black| |Once you’re below on Wings of Grace, the warmth of the upholstery, the glowing woodwork, and the traditional treatment of the deckhead embrace you and transport you to an age of grace.|

In her 50 feet, Wings of Grace has enough volume for a couple to live comfortably while still dealing with shoreside business. Nothing about the layout is cramped, and the galley is at the same time both shamelessly spacious and seamanlike. A generously proportioned guest cabin forward provides privacy for the Rindlers’ son when he visits, but since it’s usually just the two of them aboard, they chose to have one roomy head and shower compartment. Located amidships, it’s convenient to all quarters of the boat, and its partition and the galley counters opposite create a safe passageway between the saloon and the aft cabin and companionway. Leslie’s sense of color and balance is apparent in the deep-green upholstery, deep-burgundy stained woodwork, and white bulkheads and deckhead. The effect is warm, inviting, and very much in the tradition of the wooden yachts that inspired her.

French & Webb already had a good relationship with Chuck Paine, so it was natural that the firm would build her, especially given that the Rindlers had been drawn to them in the first place by the quality of their joiner work. And despite, or maybe because of, early experience with the foibles and feel of wooden boats, they were keen to have her built of wood, in the modern cold-molded wood-and-epoxy manner. Needless to say, the entire boat, from the elliptical cockpit to the aft-cabin cabinets, looks as though it were built by Stradivari.

And if Stradivari had built boats, they would’ve sailed the way Wings of Grace does.

In Annapolis, delivery skipper Andy Horner had her warped off the dock so the waves wouldn’t throw her against it, and when I boarded her after a day of hopping from one lightly built boat to another, it was like climbing onto a rock. A cabin sole that’s solid and doesn’t creak only enhances the sensation, which I remarked on to Chuck Paine after my visit in Maine.

“She’s heavy,” Paine said, “but that doesn’t make her slow.” Paine has long extolled the virtues of heavy displacement, especially when it’s matched with a generous sail plan. Despite her mainmast being lower than 65 feet so she has access to the Intracoastal Waterway, Wings of Grace carries enough sail to give her an SA/D of 18.19. The big mizzen is part of it, and it makes her easy to sail even if the wind is up, as I was to discover. And even though she draws only six feet, a long lump of ballast low down makes her mighty stiff.

At last my brief as a journalist trumped my reticence when it comes to asking personal questions. “What kind of one-man business supports this lifestyle?”

“You could call me a hospital doctor,” he said. “I don’t mean I’m a medical doctor. I make sick hospitals well again.”

“And I’m his tech support,” said Leslie. “I used to call myself his secretary, but I gave myself a promotion. Sounds much better, doesn’t it?”

Leslie also owns a gallery in Southwest Harbor where, in the summer season of June to September, she sells art-she sometimes offers paintings by Chuck Paine and his twin brother, Art-and furniture.

Michael’s specialty is rearranging the funding structure and operational efficiency of community hospitals so they can avoid being bought out by big chains. His reputation is such that hospitals now call him before they get into trouble or so that he can put them on a footing that lets them obtain financing for expansion.

Dealing with hospital boards of directors requires a delicate balance between diplomacy and directness, just the kind of skills needed to bring together a yacht designer, a builder, and a sailmaker to create with them a vessel such as Wings of Grace.

Todd French and his partner, Peter Webb, confirm that Michael Rindler is nothing if not persistent. Which is as it should be, because no great work of art or engineering arose from casual application on the part of its creators. And a yacht is a combination of both. That Wings of Grace is as magnificent as she is reflects credit to all who participated in her conception and construction.

After we finally wriggled our way out of Eggemoggin Reach and into the eastern part of Penobscot Bay, a little sea breeze began to flutter the water. We raised the mizzen, unfurled the staysail and genoa, and shut off the engine. The wind was light and fine off the port quarter, so we just moseyed along with the jib just drawing.

Sharp-edged triangles on the water ahead gradually morphed into the New York Yacht Club fleet beating down the bay toward us. A Club Swan 42 sailed close by with about nine crew dangling their legs over the weather rail.

On a beam reach as we cleared the northern end of Islesboro Island, we sailed into a brisk sou’wester. Even without the mainsail, Wings of Grace began to fly. Her sails now taut and drawing, they attracted a little more scrutiny from the deck. And what a sight they are. Set on carbon-fiber spars painted faux bois, they are the buttery color of cotton and traditionally cut with narrow panels.

“Michael was so obsessed with how the sails would look,” says Paine, “that he had us draw every panel in CAD. By the time we were done, he’d used up a good part of his budget for sails.”

“He was very particular,” Robbie Doyle, president of Doyle Sailmakers, told me later. “He wanted the color just right, and he wanted a traditional look. We ended up using the same woven Dacron fabric Contender made to our specs for the J-class Cambria, except that we used a single layer, not multiple layers. He also had us order the cloth width at 27 inches, instead of the standard 54 inches, to get that traditional narrow-panel look. The cloth is perfectly adequate for the boat, and it furls and flakes easily. We did a lot of special handwork, too, so the details look right.”

“Doyle made me buy a whole mill run of the cloth,” said Michael, “which was about six times more than we needed. By the time we were done, though, he’d found customers for most of it.”

All agree on something: Michael got what he wanted. Wings of Grace has sails that perfectly suit her appearance and her owners’ style of sailing, and all parties involved can feel proud for having contributed.

Sailing at eight knots under jigger and a couple of jibs is a rare treat in the 21st century, and it gave an indication of the power Wings of Grace must have under full sail. This wasn’t a day, though, for bashing around just for the heck of it; it was a day to bask in Maine’s summer beauty and celebrate the opening of the blueberry season. No doubt the Rindlers will have lots of occasions to cover the decks with salt spray, but I have a distinct feeling that they’re into their style of yachting for the pleasure and view with disdain the overhyped virtue of pain.

Jeremy McGeary is a Cruising World contributing editor.

Wings of Grace

LOD 50′ 0″ (15.24 m.)

LWL 39′ 6″ (12.04 m.)

Beam 14′ 0″ (4.27 m.)

Draft 6′ 0″ (1.83 m.)

Sail Area 1,430 sq. ft. (132.8 sq. m.)

Ballast 15,000 lb. (6,803 kg.)

Displacement 44,600 lb. (20,227 kg.)

Ballast/D .34

D/L 323

SA/D 18.19

Water 185 gal. (701 l.)

Fuel 250 gal. (948 l.)

Mast Height 63′ 6″ (19.35 m.)

Engine 92-hp.Yanmar 4JH3

Designer Chuck Paine

French & Webb Inc.

www.frenchwebb.com

(207) 338-6706