Recently, I received an email from a reader sharing the tale of her odoriferous holding-tank plight. She explained the tank had been added five years ago, and of late it had begun to smell. She wondered if adding ventilation might help. She was on to something.

Holding tanks are a necessary (but important) evil, and with the range of no-discharge zones increasing with each passing year, the need to have one that functions properly, and doesn’t stink, is ever more critical.

The bacteria that grow within holding tanks and sanitation systems produce, among other things, hydrogen sulfide gas. We’ve all smelled it; it’s that unmistakable, pungent rotten-egg odor. These undesirable anaerobic bacteria thrive in an oxygen-depleted environment, which is precisely what exists within most holding tanks. On the other hand, aerobic, or good, bacteria thrive in an oxygen-rich environment (it’s “good” because it digests effluent and doesn’t produce foul smells). The question is, how does one promote good bacteria while discouraging their bad brethren? The answer is simple: Add air to the holding tank.

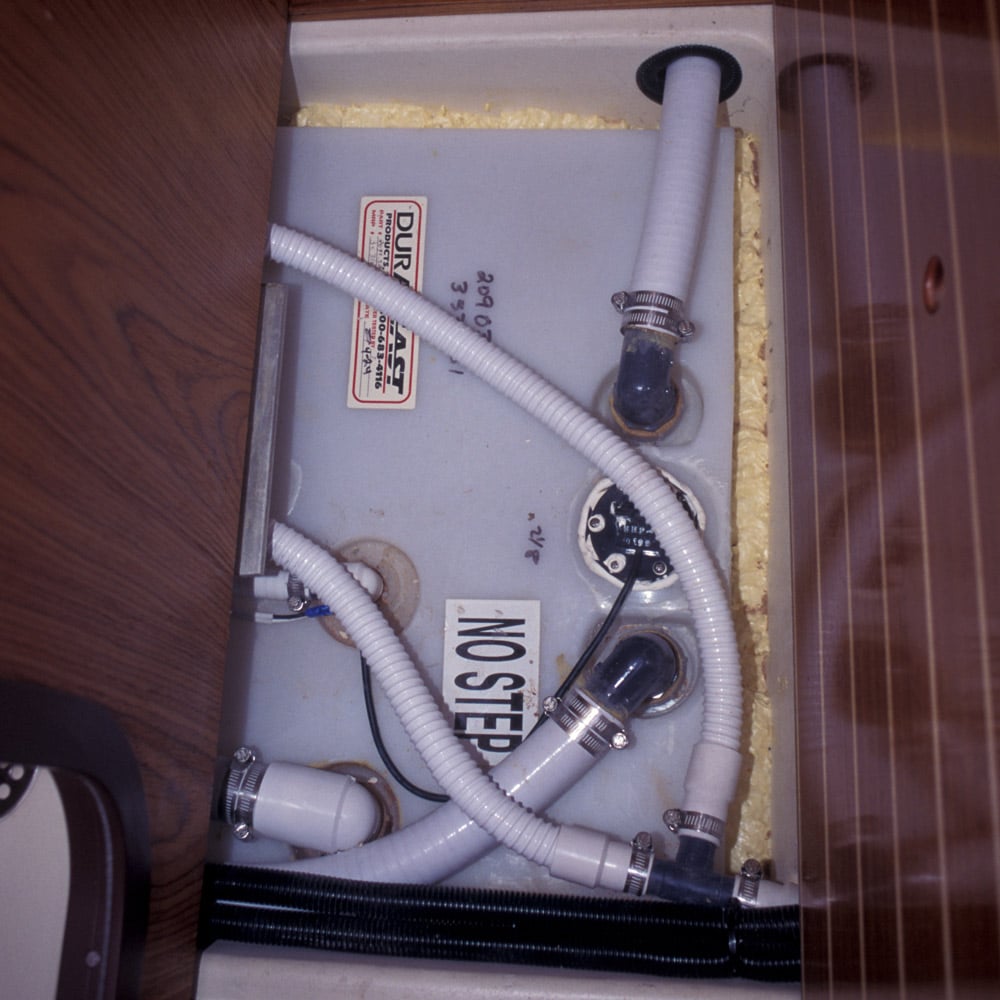

Turning a holding tank from an oxygen-depleted to an oxygen-rich environment is straightforward enough. Plumb larger and, ideally, more vents into the tank, creating cross ventilation. This can be accomplished in one of two ways. The first involves the installation of two 1½-inch-diameter vents to the tank, preferably at opposite ends, each of which is then plumbed to different sides of the vessel. (There is nearly always a slight difference in pressure between port and starboard sides, especially when under sail.)

RELATED: Odor Beaters: Holding Tank Ventilation

With this arrangement, constant airflow through the tank discourages bad bacteria, and dilutes odors overall. This plumbing is easiest to install when the vessel is being built or refit because aftermarket installations can be challenging. If 1½-inch hose won’t fit, go as large as possible; ¾ inch or 1 inch is better than the commonly used ½ inch or 5/8 inch. If even that’s impractical, the second approach involves the installation of an active ventilation system, one of which, called the Sweet Tank, is offered by marine plumbing manufacturer Groco. It utilizes a small air pump not unlike the bubblers used in fish tanks to constantly introduce a fresh supply of air into the tank’s liquid. It doesn’t use much power; however, even if run only when the engine is on, or while dockside and plugged in, it will help.

Charcoal holding-tank vent filters, while seasonally effective at neutralizing odors leaving the tank via the vent, tend to impede cross ventilation. If the filter gets wet from an overflowing tank, or from water being pushed back through the vent, it becomes ineffective, and it can swell, blocking airflow.

Yet another advantage to the larger vent(s) is that it is nearly impossible for them to clog, and thereby avoid tank pressurization, or a tank implosion, during filling or pump-outs, respectively. These make implosion preventers unnecessary.

When I first began prescribing this approach to boatbuilders, during new-build or refit projects, I received some quizzical comments. “You want a 1½-inch holding-tank vent?!” they would ask. “No,” I would reply. “I want two of them.” Most were reluctant; some got it right away. The bottom line, however, is that it does work. Fresh air is all that’s needed to change the chemistry inside a holding tank. Even a whiff of nonaerated, and thus anaerobic, bacteria-laden effluent gas can make an entire cabin uninhabitable. Thus, an added benefit of the superventilated holding tank is a less smelly tank interior, which in turn is less likely to exploit weaknesses in the system elsewhere. In other words, if the gas in the tank doesn’t smell so bad, it’s less likely to noticeably permeate hoses and other fittings.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.