After 30 years of patiently suffering my proclivity for such unnecessary hardships as a leisurely winter cruise around Cape Horn, or icing into the high Arctic wilderness, my wife, Diana, asked that once — just once — we take a normal holiday. Her vision was clear. This would be tourism as opposed to adventure, with no hull-thumping gales, charging polar bears or violent revolutions. Whatever our chosen destination, we must fly there, not sail. And we would stay in hotels — on land, of all places!

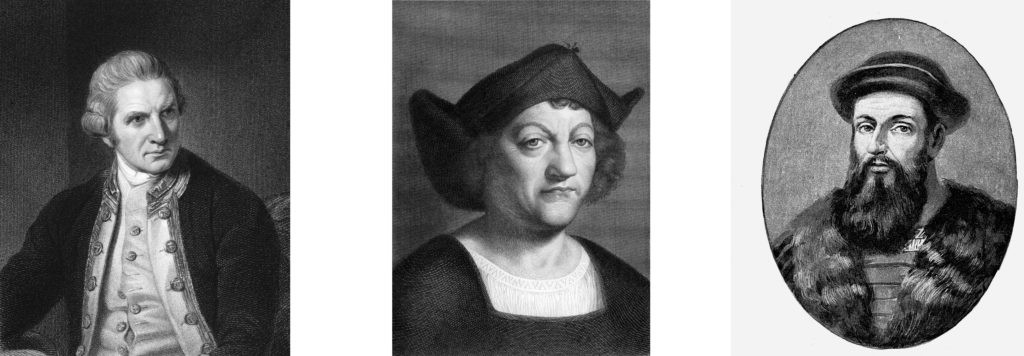

Reluctantly, out of a sense of fairness, I acquiesced. We chose Spain. In 12 hours we flew across an ocean it had once taken us two months to sail. It felt like cheating. Madrid felt mighty far from the sea. But, as we traveled south and west from there toward the coast, a sea breeze began to stir up the salt in my blood and brain. In the ancient city of Seville, we found a cathedral dripping with the riches so brutally extracted from the New World. In an ornate tomb lay the hallowed remains of Don Cristobal Columbus, the Admiral of the Ocean Sea, ultimately one of the most influential, even if not skilled, sailors and navigators in human history.

This may not sound awfully exciting unless you put it into the context of a bird watcher finally spotting her lilac-breasted roller, or a big game hunter completing his quest for the Big Five.

Years earlier I stood on the beach in the Philippines where Ferdinand Magellan was murdered. Had he lived, he would have been the first man known to circumnavigate the globe. As it turned out, that honor went to his cabin slave, Enrique de Malacca. Magellan made his journey on a cumbersome vessel, crewed by murderous mutineers driven by dark superstitions and deterred by drawings on his primitive charts that warned, “Beyond Here Thar Be Monsters.” Think what skill, bravery and determination such a voyage into the unknown must have demanded.

On another occasion I stood on the beach in Hawaii where perhaps the world’s greatest seaman and explorer, Capt. James Cook, was slain. Unlike Magellan, Cook’s death did not cut short his maritime achievements, for he had already explored more of the globe than any man in history before that tragic day. Even today, with our impregnable hulls, computerized weather forecasting and GPS, few dare venture into the waters that Cook not only sailed but meticulously surveyed.

I’ve stood on the very hill in Panama’s jungle where Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez Balboa caught the “first” glimpse of the mighty Pacific Ocean. Diana and I have probed the waters that Henry Hudson mistakenly thought would lead him to the Northwest Passage and the riches of the Spice Islands. Vasco da Gama, Matthew Flinders, George Vancouver, William Dampier, Vitus Bering, John Cabot, Abel Tasman, Bartolomeu Dias — the litany of seafaring legends seems to have faded into mere historical footnotes, save the few who were fortunate enough to have had a cape or island named after them. But it is always a thrill to cross their paths, so to speak, as the historical perspective enriches our cruising.

But to get to the roots of our sailing heritage, Diana and I had to go much further back than the European Age of Discovery. We drove down to Cadiz, founded nearly 3,000 years ago by the earliest of the great sailors, the Phoenicians. While looking out over those ancient parapets, I wondered how many sailors over the millennia, like Columbus, had started their voyages from these very waters, probing south to the great capes of Africa, west to the Grand Banks, and beyond. Columbus returned to fame and fortune, but how many stories will forever be muted by misfortune and shrouded in mystery? On land our famous historical paths, such as the Appian Way, are etched into the terrain, creating a physical connection with the past. But the sea keeps its secrets. The great seafarers of yesteryear, especially those like the Polynesians, who relied solely on oral tradition, left nothing behind them but an ephemeral wake.

Still, we can but marvel at their skill and bravery, and appreciate the tortuous yet incremental progress that each perilous voyage contributed to the knowledge of our planet and the sophistication of our vessels today.

Alvah Simon is a CW contributing editor and author of North to the Night. He and his wife, Diana, are actively cruising the South Pacific on board their 36-foot steel cutter, Roger Henry.