It’s time we sailors pay more attention to the problems that loom right in front of us on the bow. On many sailboats, potential neglect there goes unheeded because much of the gear forward of the mast hides belowdecks, out of sight from the sailor at the helm.

Yet anchor chains and dock lines decide how safe your boat will be secured in rising wind and fast-building chop. And on the foredeck, the chain leads and stoppers, the anchor stowed on its roller, and the location of bollards or cleats all require careful thought to ensure ease of use and safety in all conditions. In addition, several other fittings in the bow area will help or hamper sail management when sailing downwind.

Let’s begin with the anchor locker. The space in the forward section of the boat under the deck and in front of the ubiquitous V-berth has to provide enough space for ample lengths of one or more anchor rodes. For a bluewater boat that’s sailing to remote areas of Earth’s oceans, ground tackle should consist of 300 to 400 feet of chain and a backup 600 feet of coilable line with a 40-foot chain lead. Traditionally, on many boats, the primary anchor chain stows on the starboard side of the locker. The port side receives the line-and-chain combination reserved for deploying a second anchor in demanding conditions. A partial fore-and-aft bulkhead should separate the two.

Apart from the conveniently shallow waters of a few cruising destinations in the world — the Bahamas, or inland waters like the Chesapeake Bay, come to mind — many anchorages are quite deep. To be able to anchor at a safe distance from hazards to navigation and still keep a prudent 6-to-1 ratio of anchor chain to water depth, one needs much of that 300 feet of all-chain rode. For high latitudes and the Pacific, 400 feet of chain will work better. Otherwise, it’s sometimes necessary to add line, which complicates the operation of an electric or hydraulic windlass. (For smaller, lighter sailboats, say up to 40 feet in length overall, with manual windlasses, combining chain with rope is, of course, perfectly acceptable.)

Many of today’s production yachts provide anchor-tackle stowage in a well that is accessible through a hatch on the foredeck. Unless it’s very large, such space might be inadequate for bluewater cruising; an additional ample length of rope rode must be stowed elsewhere. Besides adequate anchor-line storage, the ideal arrangement for a far-ranging cruising yacht is a windlass located a good distance aft of the bow but ahead of the mainmast. A deep chain locker under the windlass would then provide the best weight distribution for correct boat trim. Keeping heavy weights close to the middle of the boat prevents pitching, and is particularly vital for light-displacement yachts. Well-designed custom sailboats normally incorporate such a layout, but by applying inventive thought and adaptation, many production models can be brought up to this standard.

On the foredeck of our boat are two open fairleads, two closed fairleads and two large cleats on either side. We added these large open fairleads, with perfectly smooth rounded corners, to use with bow lines and anchor snubber lines. Occasionally, we have to run two lines through a fairlead; for example, a bow line and a spring line. The closed fairleads, which came with the boat, lack generously rounded corners, and they are also too small to run two lines through without chafe. We also added two more cleats, so now a bow line and a spring can run through a separate fairlead and lie on their own cleat. This makes it easy to adjust the lines under load.

The fairleads and cleats also do quite a bit of work while sailing downwind with a headsail or two boomed out on spinnaker poles. The forward fairlead receives a foreguy, and the closed fairlead receives a preventer line of a fixed pre-cut length. The preventer holds the pole back from banging into the headstay while we tension the topping lift and the genoa sheet, the latter acting as an afterguy. Attaching all the lines to the end of the spinnaker pole is often awkward while the boat rolls wildly in swells. To immobilize the pole, we drop it into a U-shaped fork on the bow pulpit. Normally stowed away, the fork slips when needed into one of the short pipes installed on the outside of the pulpit tubing.

Recent developments in downwind sail design have introduced some variants to the fittings on the bow. Hoping to do away with spinnaker poles calling for labor-intensive rigging and energetic sailhandling, sailmakers came up with various light sails under names such as asymmetrical spinnakers, screechers, gennakers, jib-tops and, in keeping with the digital age, code zero and code one.

They definitely help achieve impressive speeds in light conditions, but to set them, they require new fittings on the bow to get their tacks forward of the headstay and furler. They also need to be farther forward to extend their useful performance into apparent wind angles aft of broad-reaching. On racing boats, you will see poles, or sprits, as they’re called, emerging from their own storage tunnels within the bow areas. Cruising boats have a choice of sprits stowed on the foredeck. They run through a collar on the bow and are either retracted or extended forward when needed.

The loads created by these humongous sails can be considerable, so on boats over, let’s say, 40 feet, the extenders often come as hinged or fixed A-sprits supported by fixed or adjustable bobstays. But even the largest of these sails will not fill when running directly downwind. Dropping the mainsail or moving the foresail tack onto a whisker pole or dedicated spinnaker pole is the only solution when a course directly downwind is necessary.

So, on days when you’re at the helm, skimming along under blue skies, the bow might seem far away and out of mind, but to ensure trouble-free ocean roaming, look around and inside the lockers forward. Is there enough anchor tackle for all conditions? Do you see adequately strong fittings to tie up in strange places with fixed docks, or enough leads to run all the lines when getting ready for a run downwind? If not, start making your winter to-do list of improvements now.

In a perfect world, the chain locker should be enclosed from the boat’s interior with a watertight bulkhead that has a watertight door for comfortable access from below, in case attention to the rode is necessary in order to undo tangles or flake the chain down while hauling it in. Otherwise the incoming chain might pile up, and while the boat rolls on the way to the next destination, the heap could slip into a nasty tangle. If this occurs, just as you try to drop the anchor in the best spot in a crowded anchorage, the twisted chain will jam under the deck.

For offshore work, a hawsepipe on deck is preferable to an opening locker that could let in volumes of water. Employing a pipe makes access from below to the chain locker essential. An opening into the locker that lacks a sealable door will allow seawater to squirt onto the V-berth through the chain opening in the deck. There are a couple of ways of sealing off this deck hole, however. Some people disconnect the chain from the anchor and hook the last chain link on the underside of a plug that fits tightly into the chain opening. An alternative is a cover plate with a slot cut in one side that matches the chain size. It slides over the opening and is held in place by a thumbscrew bolt in the deck. In really rough going, small amounts of seawater might seep down the chain and end up in the bilge. An automatic bilge pump easily clears that out.

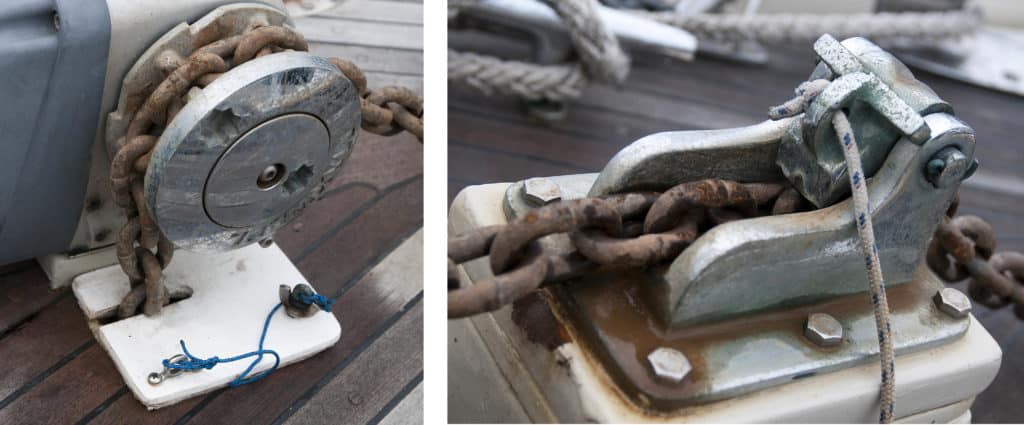

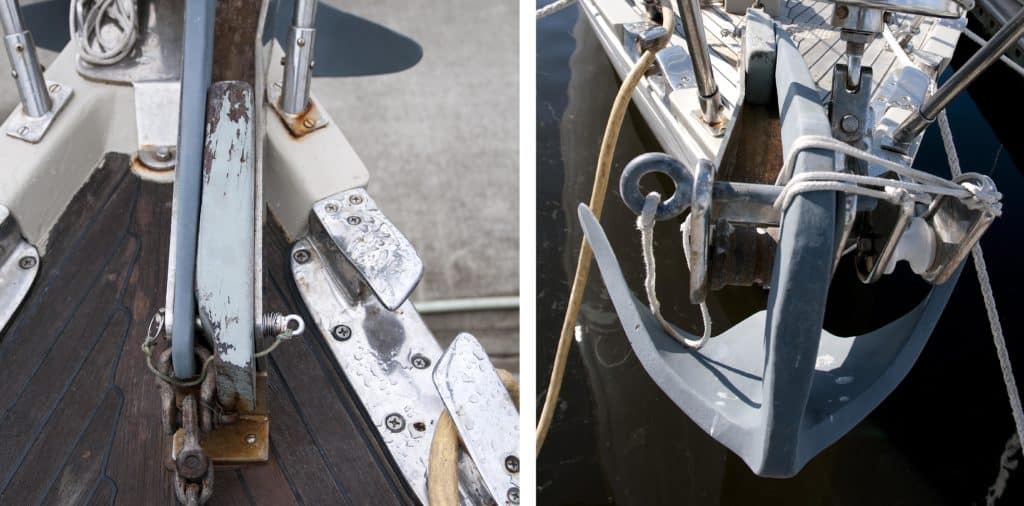

The backup soft line anchor rode with a chain leader comes into its own when the wind’s song rises to an ominous pitch. On our Mason 44, Frances B, I reach it through a 6-inch-diameter port on deck. I pull the chain up, shackle it to a spare anchor of the type suitable for the bottom in the anchorage and, voilà, it’s ready to go. This anchor rode rides on the portside bow roller, which is made of Delrin, a strong plastic that’s kind to soft nylon lines.

The all-chain starboard rode runs from the windlass through a pawl-type chain stopper and then through a stainless channel to its heavy-duty bronze roller. When all the necessary length of chain has gone out and we are about to back up the engine to set the anchor, we engage the chain stopper, which takes over the load and protects the windlass.

The stainless-steel channel protects the deck while the chain is running out. The sides of the channel have two sets of strategically placed holes that we use to help immobilize the anchor at sea. The forward ones receive a large pin that goes through the anchor. The aft ones receive a pin that goes through a hardwood wedge and the anchor. This wedge locks the anchor firmly in the channel. To further prevent anchor movement at sea, we lash it tight with a length of Spectra at the forward end of the channel.

Tom and Nancy Zydler have spent the past several seasons plying North America’s East Coast and the Canadian Maritimes aboard Frances B, their Mason 44.