As we rounded a bend on the Missouri River, swallows darted from the sandstone cliffs, sending shadows across our red-and-white sail. Our flotilla came into view: a motley crew of canoes and kayaks haphazardly pulled up on shore, above which our friends lounged near a grove of cottonwood trees, enjoying Montana’s spring sun. My 3-year-old son, Talon, stopped playing with a rope long enough to ask, “Is that our campsite, Mom?” It wasn’t. We were only 3 miles into a 50-mile float down the National Wild and Scenic section of the upper Missouri River, part of the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument. Our friends were simply waiting for us to catch up. Since this was our maiden voyage in the sailing canoe, my husband and I had launched later, taking extra time to set up the collapsible mast — and to strategically pack all of the gear we needed for a five-day family expedition. Once underway, though, we caught up in no time. The downriver wind was a lovely 10 knots, pushing our lightweight canoe along at 8 knots. And when the wind was blocked by the river’s famous white cliffs, we simply paddled leisurely with the current until the sail filled again.

Our friends cheered as we cruised past, excited by the novelty of seeing a sailboat on a river. We beat them to the evening’s campsite handily, their paddles no match for the steady wind.

Just a few hours in, I was hooked on the benefits of canoe sailing. Four years ago, my husband, Rob, and I sailed across the South Pacific, hitchhiking as crew on a variety of monohulls. When we returned to Montana after a year at sea, we searched for the best boat to fit our mountain-town lifestyle.

A standard yacht wouldn’t meet our needs for exploring Montana’s abundant lakes and rivers. Since we didn’t own a truck to tow a 5,000-pound monohull, we’d have to pay expensive dock and storage fees at a marina and stay on just one lake during the Rocky Mountains’ short sailing season. Instead, we began looking at a variety of lightweight-sailboat options — including folding trimarans and sailing canoes — that we could transport with our sedan.

The sailing canoe was, hands down, the most versatile and affordable option, as well as the easiest to maintain and store.

Although we (briefly) considered a do-it-yourself sail rig, we wanted something sturdy and dependable for our family. That’s why we bought an $800 folding sail kit from Sailboats to Go. Plastic pontoons across the bow keep the canoe as stable as a catamaran. Beside them, leeboards help the canoe track when sailing close to the wind. Since the lateen-rigged sail swings all the way around the aluminum mast, it is easy to release the sheet to prevent capsizing or broaching when there is too much wind.

The cruising life isn’t complete without a lively jam session, and a ukulele is the perfect instrument aboard a small boat.

The whole kit weighs less than 50 pounds and fits into one duffel bag that can be checked as luggage on airplanes — a huge selling point for us. My husband and I have a long wish list of places we want to sail. Now, by renting a canoe and attaching our mobile sail rig, we can cruise in places such as the Florida Everglades, the San Juan Islands in the Pacific Northwest or the Great Lakes for a fraction of the cost of chartering a sailboat.

For closer-to-home adventures, we bought a used 15-foot Coleman canoe. It’s beamy, durable and roomy, with a square transom to hold a 3 hp outboard. The whole setup fits in (and on top of) our small sedan.

As we sailed down the “Mighty Mo,” Rob and I were giddy about our new craft. It felt satisfying to go back to basics: No flapping genoa to sheet in. No keel to worry about in the shallow water. No electronics to stare at instead of the scenery. Just one sail, an oar as a rudder and a telltale we’d made out of yarn. Simple.

And simple felt like the perfect way to follow in Lewis and Clark’s footsteps down the longest river in North America. It was fitting to see this rugged country from the same vantage point as the West’s famous early explorers.

For three weeks in May and June 1805, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark plied this same stretch of the upper Missouri River. The explorers began their expedition exactly one year earlier, leaving from St. Louis to chart the unknown territory west of the Mississippi. By the time Lewis and Clark reached central Montana, they had 33 people in six dugout canoes and two pirogues (large six-person flat-bottomed boats made to carry 8 tons of cargo).

Unlike us, though, Lewis and Clark had to travel upriver — against the current. No small feat, especially in the spring, when Montana’s rivers are swollen with snowmelt. Crews of men walked along the shoreline, towing heavily packed canoes with ropes, sometimes carrying the boats and gear around massive logjams where fallen trees made the river impassable.

A couple of weeks later, the expedition ditched the large pirogues entirely when it reached a series of waterfalls that required portaging several miles, a place now named Great Falls. After leaving the Missouri, it would take the explorers another five months to reach the Pacific Ocean in Oregon.

This stretch of the upper Missouri where we sailed hasn’t changed much in the past two centuries, and is still renowned for its remoteness and beauty. Like me, Lewis noted the elegant flight of swallows in his journal, as well as the majestic white cliffs as they traversed the 800-foot-deep canyon: “It seemed as if those seens [sic] of visionary inchantment [sic] would never have an end.” Today, floating the White Cliffs section is one of the few still-unspoiled portions along the 3,700-mile Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

As we sailed through the canyon on day two, my son pointed out rock formations that looked like animals while I scanned the riverside cottonwood groves with binoculars, counting dozens of species of songbirds flitting among their shimmering leaves. We pulled the canoe ashore midday to hike to a spot where we could peek through a round hole in the rock face. Our little red sail looked bright against the green grass below.

Two hours later, we arrived at camp. Unloading our boat quickly, we set up the tent and cook station so that we could spend the late afternoon traipsing around in the sagebrush. Talon scampered down bright-white sand dunes that were calcified and salty from hosting an ancient sea, while Rob scaled a tower to a ridge top, spotting pronghorn antelope and soaring hawks in the distance.

Its one-of-a-kind geology is one of the reasons we’d chosen the upper Missouri as our first voyage in the canoe sailboat. We found fossils and petroglyphs, caves and canyons, and plenty of jaw-dropping vistas under Montana’s Big Sky.

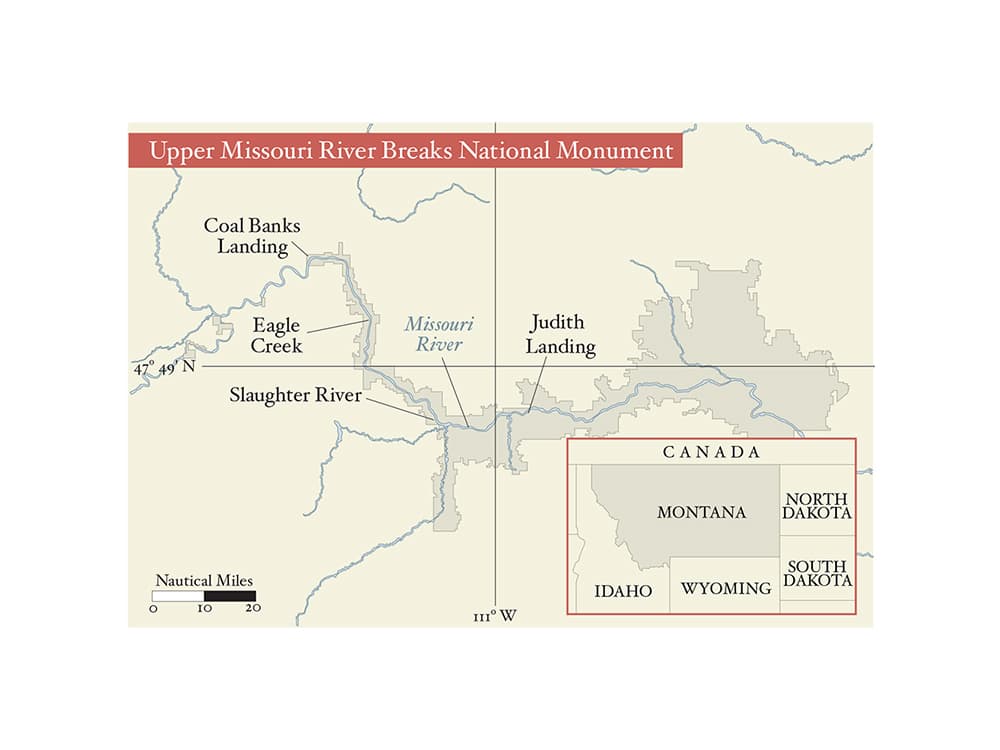

All told, we passed three campsites used by Lewis and Clark during our float, as well as dozens of other historic spots: tepee rings used by Native Americans; old fur-trading posts; dilapidated steamboat landings from pre-railroad times, when the Missouri was the best means to travel west; and homesteads long abandoned by the pioneering families who farmed along the river’s banks. Even the names of the campsites at which we stayed — Hole in the Wall, Slaughter River, Eagle Creek, Judith Landing — were reminiscent of pioneer times.

Our final day, we lingered on the river after saying goodbye to our friends. Weaving our way into sloughs and side channels, we found abundant pockets of birds and fish. My husband cast for catfish along the banks while I tacked back and forth, seeing how much progress we could make sailing upriver.

Eventually, we turned toward the setting sun and the end of our adventure. I let the sheet out, the downriver wind filling our striped sail one last time. My son giggled as he tried to catch the spindrift flying off our bow wave.

“Mom,” he announced, “I like being an explorer.”

Brianna Randall is a writer based in Missoula, Montana, where she plays outside as much as possible. She and her family have big plans for Big Sky-based expeditions in their sailing canoe this summer. Follow their adventures at briannarandall.com.

A Canoe for Cruising

The sailing rig we used came from sailboatstogo.com and fits most canoes. It includes a 55-square-foot nylon sail mounted on spars that slide down the collapsible aluminum mast. A bow crossbar clamps to the gunwales and accommodates a mast step, a downhaul, retractable leeboards and plastic pontoons for stability. There is also a stern crossbar that holds the steering oar (some canoe sailors choose to buy two steering oars rather than transferring one oar from side to side when tacking). This standard kit runs about $800, depending on options.