I still get butterflies. I’m 64 years old and have actively lived aboard and cruised offshore for 56 of those years. I just wrapped up my third circumnavigation, yet I still get flutters in the pit of my stomach when I utter my two favorite words: “Cast off!”

Why?

It isn’t that I’m scared. I’m less fearful offshore than I am walking down the streets of my native Chicago. It isn’t that my boat isn’t properly prepared, because I know she is seaworthy within the rational parameters of time and money. Sure, my wife, Carolyn, and I could always be more prepared if we postponed our departure to spend additional time and money — but then we’d never actually leave, would we?

The butterflies certainly aren’t because I don’t know what to expect at sea. I fully anticipate encountering a strange mix of mental ecstasy, tediousness, stark terror and physical ordeal continuously mixed in odd proportions.

Let’s face facts, the cruising lifestyle is amazingly diverse. Your payoff will be directly related to your pay-in. Part of the charm of sailing offshore is its amazing difficulty. If not, a sailor stepping off a cruise ship and a sailor stepping off a small cruising vessel would have the same sense of accomplishment. They do not. The cruise-ship tourist watches the world go by; he is a voyeur and risks nothing. The offshore sailor, however, risks it all: his life, his pride and, most of all, the lives of those he loves the most. The offshore sailor creates his entire watery world, along with its myriad challenges. He is an active participant, not a rubbernecker.

This is easiest seen in second-generation sailors. While our daughter, Roma Orion, was growing up aboard, her best friend was another cruising child named Kylie, who lived on the sturdy wooden ketch Gaucho with her father, “Speedy” John Everton, and her mother, Roni. Kylie was a wonderful girl and a great daughter, though she was often bored at sea, just as our daughter, Roma, was. But recently Kylie and her longtime partner, Wil, sailed over the horizon on their own boat, a lovely twin-masted cowhorn, and her whole perspective on the cruising life changed.

The first thing that amazed Kylie was all the hard work and responsibility involved. “I just let my parents do everything, like any boat kid does. It never dawned on me how many different, difficult levels they were working on.”

The second thing was the vast difference between having some input into a navigation decision and actually making that decision — accepting responsibility for it, putting your life on the line with it.

“The first few days offshore, it seemed like we had to make a million decisions, and each one was vitally important. It sort of freaked us out for a while,” Kylie told me.

Gradually, she and Wil became more confident and bolder in their choice of destinations. They have now sailed the Caribbean, the Bahamas, Florida and are currently gunkholing along the East Coast of the United States.

“The sense of accomplishment is totally different between adult captain and child passenger,” she says. “Nothing is lightly done when it is your hand on the tiller. But as a result of that, the payoff is all the sweeter too. I now savor the passages, just as my parents used to. Our pride isn’t merely in reaching our destination but in the seamanship required along the way. Yes, it’s true: The difference between ordeal and adventure really is attitude!”

I predict that Kylie will never, ever be bored at sea again.

I still remember rowing away from Elizabeth, our family schooner, for the first time. Ditto the first time my father rigged Lil’ Liz for me and I went dashing off through the Vinoy Basin in St. Petersburg like a scared cowboy on a runaway horse. Both experiences were thrilling and empowering. But they were nothing compared to the gulp I took when buying my own boat at age 15. I knew even then that a boat owns you as much as you own it. And this purchase, made in isolation, without parental consent, would either go down in my personal history as my first major failure or my first big success.

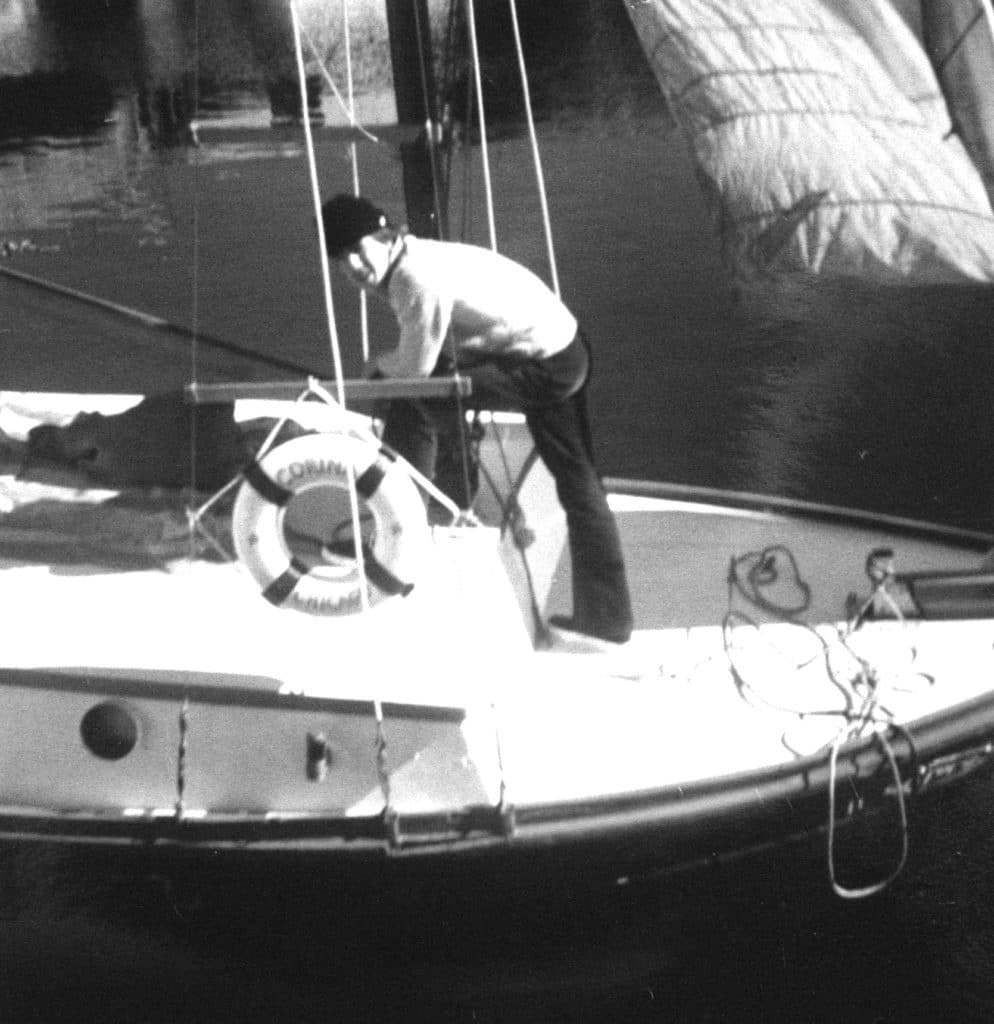

Yes, I had butterflies in my stomach when I told Mr. Joyce I’d buy her. Almost immediately after shaking hands, however, reality set in. I’d just bought a boat with no rig, no running engine (it was disassembled and rusting in the bilge), and which had been broken into and used as a gang hangout for months.

None of this damage would fix itself. Only I could make it right.

I rebuilt the Universal Atomic 4 with $45 worth of used parts, then, with my best friend George Zamiar, powered her over to the dock at the just-opened posh Marina Towers on Chicago’s riverfront. I strolled up into its fancy restaurant in my work clothes, grabbed a table, ordered two Cokes, looked down with pride at Corina and loudly said, “Now that’s the life!”

“Ain’t she pretty!” George replied.

At that moment, I became a man, meaning I fully accepted responsibility, both good and bad, for my actions.

Soon I found where the rig was stored ashore and purchased a used jib for $10 and a mainsail for $15. That summer, at age 16, George and I cruised Lake Michigan and were both forever changed. We became (briefly) the toast of Saugatuck, Michigan, invented the Green Slime religion, made a ton of money in the jewelry business and were arrested (again, only briefly) for corrupting the morals of every kid under 21 for a hundred miles around. Guilty! I never had so much fun, and I realized I owed it all to my boat. Suddenly, I knew it wasn’t just a tiller that I had in my young hand, I had my destiny. At an early age, I realized that the butterflies were my friends; they heralded a million things that could go wrong — or right!

I had the butterflies at 19, as Carolyn and I checked out Howard Chapelle’s book on boat building from the Boston Public Library, but there was no doubt we deserved the cheers three years later when we splashed Carlotta, our 38-foot, 20,000-pound Peter Ibold-designed ketch in the Fort Point Channel.

And I had butterflies in my stomach when my wife nonchalantly mentioned, in Bequia, that her biological clock was ticking. But we worked it out nine months later when Roma Orion was born and I ripped out the darkroom in the forecastle to construct a teak nursery.

I had a belly full of butterflies when I asked Carolyn if she’d like to circumnavigate a time or two. And ditto when I told her I was going to earn our living as a writer.

Ultimately, I’ve come to understand that those butterflies in my stomach aren’t harbingers of fear but rather the delightful tingles of change. I’m an adventurer. In my mind, routine equals rut. My goal is to do something, anything, even if it is wrong. And amazingly, I have found a life partner who agrees.

“I’ve often been hungry but I’ve never been bored,” Carolyn tells people. “I never met anyone who dreamed as big as Fatty.” This past year, we embarked on a 6,000-nautical-mile passage from Southeast Asia to Cape Town, South Africa. And from there, we set sail again, bound for the Caribbean. We left knowing that these oceans, the Indian and then the Atlantic, would test our vessel, our rig, our relationship and our love to the max. There would be moments of stark raving terror and long spells of extreme discomfort. There would probably even be moments during which I’d think I’m out of my depth, that I’m too old, that I’m too senile for the immensity of the challenge. Moments might even occur when I’d realize that my wife is a better sailor than I’ll ever be. So be it.

I’m not ready for the rocking chair yet. I do not aspire to address yacht clubs. I still live to see God’s face in every ocean wave. How do I know this? Because my butterflies tell me so!

The Goodlanders are currently fluttering somewhere toward a watery waypoint in the Lesser Antilles.