About 6,000 years ago — when the Pacific Ocean was unexplored and its tiny islands, scattered across a vast area of unimaginable size, lay quiet and uninhabited — a pioneering people from Southeast Asia pushed their double-hulled canoes from familiar shores and sailed deep into the unknown.

For over a millennium they migrated east, toward the rising sun, settling on islands never before seen by mankind, raising families and building communities before a brave new generation set sail to explore farther beyond the horizon. And while the remote islands evolved over generations into the separate regions and countries we know today as Hawaii, New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, the Cook Islands, French Polynesia and Rapa Nui (Easter Island), they remain connected by the wakes of their ancestors, like the lines of an ancient family tree. And remarkably, while separated by time and by a vast ocean, the connection between the Ma’ohi, the Polynesian people, is not only remembered, but is celebrated even today.

For centuries, the rich culture and untamed beauty of the Marquesas islands (Te Henua Enana in local dialect, or “Land of Men”), which lie more than 700 miles northeast of Tahiti, have drawn artists and writers to their remote shores. Paul Gauguin, Herman Melville and Thor Heyerdahl were each seduced by the dramatic archipelago, and either on canvas or on paper, set out to capture its wild beauty. The Marquesas awakened something deep within them, a raw, powerful emotion that influenced not only their work, but the rest of their lives.

And so it was here, far removed from a busy and distracted modern world, that the Marquesan Festival was born, a unique arts and cultural event celebrated only every four years. An event held not for tourists, but rather for the proud Ma’ohi people, a people who, even after thousands of years, remain connected by a strong spirit, one that spans an ocean and continues to unite its true discoverers.

My wife, Catherine, and I first heard about the festival during our own migration east across the Pacific in Dream Time, our 1981 Cabo Rico. We had arrived at the remote island of Raivavae after an arduous 28-day passage from New Zealand back to French Polynesia, and although at first the Marquesan cultural event seemed more rumor than reality (no one we spoke to could agree on when it would begin, nor which Pacific Islands would attend; even the island hosting the festival was in question), the uncertainty and mystery surrounding the unique festival only made it more alluring. And so we set off, sailing northeast, tracing the ancient wakes of the Ma’ohi canoes up to the Society Islands, across to the Tuamotus and toward the Land of Men.

We arrived in the Marquesas just three days before the festival. Delegates from Rapa Nui, Rapa Iti (Austral Islands), Tahiti and New Caledonia had already gathered, and an energy was building. You could sense it, like an approaching summer storm. The air — heavy, humid, unsettled — carried with it the rhythmic and alluring rumble of distant drums as groups practiced into the tropical night. Something powerful was coming. Remote villages hidden in ancient valleys and shrouded in jungle were awakening. You could feel it.

RELATED: On Watch: A Festival in French Polynesia

Then, over four exhilarating, spellbinding days, we lost ourselves to the rhythmic beating of the pahu, the drums, and to an energy that seemed to swell up and saturate the ancient stone me’ae and tohua, sites where distant ancestors performed tribal ceremonies and ritualistic sacrifices. We sat not in bleachers or behind barricades, but on smooth volcanic boulders beside the dancers. In the midday sun, we stood under the shade of a 300-year-old banyan tree behind the booming drums, close enough to feel the vibrations resonate deep within us. And in the evening, we sat among the long dancing shadows of more than 200 performers, who stirred the earth with bare feet and shook the air with one voice. A voice that seemed to reach back through the ages, echoing down through the craggy folds of valleys and out to sea.

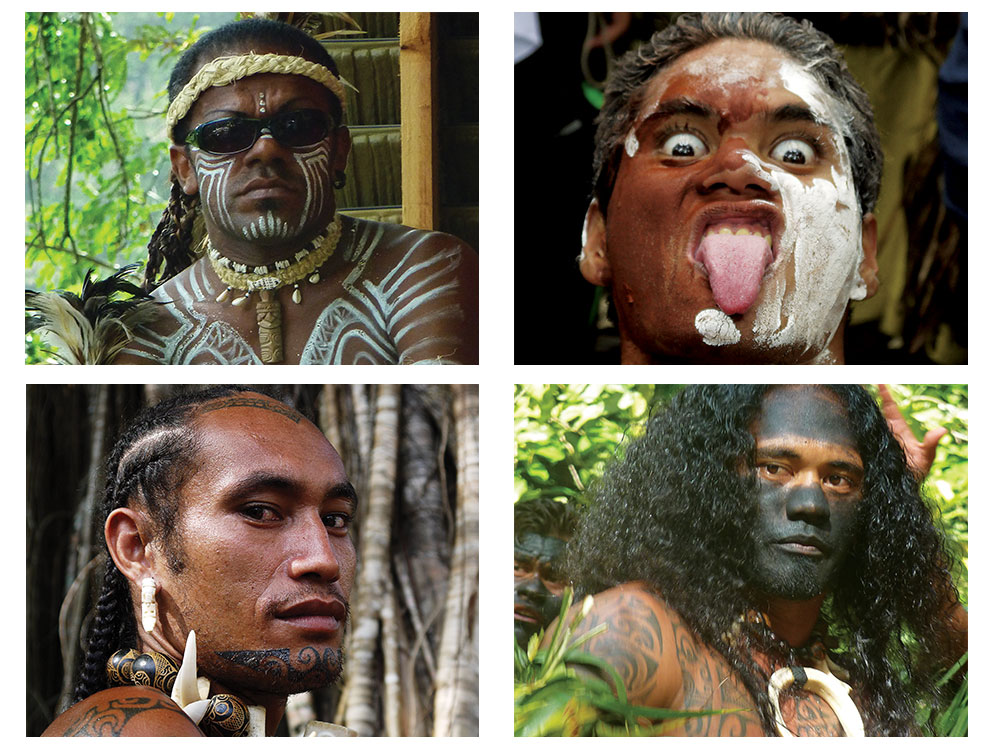

We came to recognize faces and personalities; we felt connected to them. We walked among performers dressed in tapa cloth and adorned with shells, flowers, feathers, seeds, pearls and bone. Cracked paint and Marquesan tattoos covered bare skin. Under palm-frond lean-tos, traditional Polynesian arts were demonstrated: the dull hammering of wet bark into thin tapa cloth; the painful tapping of blackened tusk needles against exposed skin as intricate Marquesan tattoos took shape; the metallic ringing of chisel meeting rock; weaving; wood carving; canoe building. These traditional skills were shared and practiced by a new generation of master carvers and artists who, through their passion and their work, continue to keep an ancient culture alive.

Through song, dance and gesture, each cultural presentation told a story: an elegant rotation of a wrist; a subtle movement of a finger; an aggressive tilt of a head; a suggestive swaying of the hips; bared teeth; wide eyes. Every action and motion held a message, a story from the past, and even though we could not understand the words, we felt like we came to understand their meaning. We found ourselves rocking and swaying with each performance, to drums that, even in the tropical heat, raised goose bumps on our arms; drums that flowed and ebbed like the wind with a seductive and consuming rhythm; drums that seemed to lift the dancers from the ground and carry them away, away from this world and back to another time.

And we went with them.

As our epic eight-year voyage across the South Pacific comes to an end, I can still hear the rhythmic and provocative beating of the great drums, the haunting cries of the female dancers, the guttural murmurs of warriors preparing themselves for dance. I can still feel the black, gritty volcanic sand on my skin from those remote tropical islands and smell the rich, sweet scent of monoi oil in the air, mixed with the smoke from burning coconut husks.

The South Pacific has been the highlight of our world adventure. The scattered constellation of tiny island groups across charts that were once so foreign, distant and unknown feel familiar to us now, like home. Each cluster of islands holds precious memories, some of the best in my life, and as we sail west, toward Australia in preparation for Asia and a new ocean, the next generation of cruisers are about to begin their epic voyage across the world’s largest ocean, and it is something to behold.

Neville and Catherine Hockley have been outbound on an open-ended cruise since 2007 aboard Dream Time, their Cabo Rico 38. Follow their adventures on their website.