The wind’s blowing 20 across confused seas as a 5-foot swell reminds us Hurricane Chris went by not long ago. It’s a great day for my dad, my nephew and me to sail the Nova Scotia coast. We steer a broad reach at 7 knots, and that takes the sting out of the gusts as we wend through lumpy seas like a skier through moguls. It’s not all good times; the sky’s gone the color of old nickels, and our boat skids awkwardly off every 10th wave. Still, there’s plenty to like for three generations of McCarthys aiming south from Shelburne onward to round Cape Sable for a night on the Bay of Fundy shore.

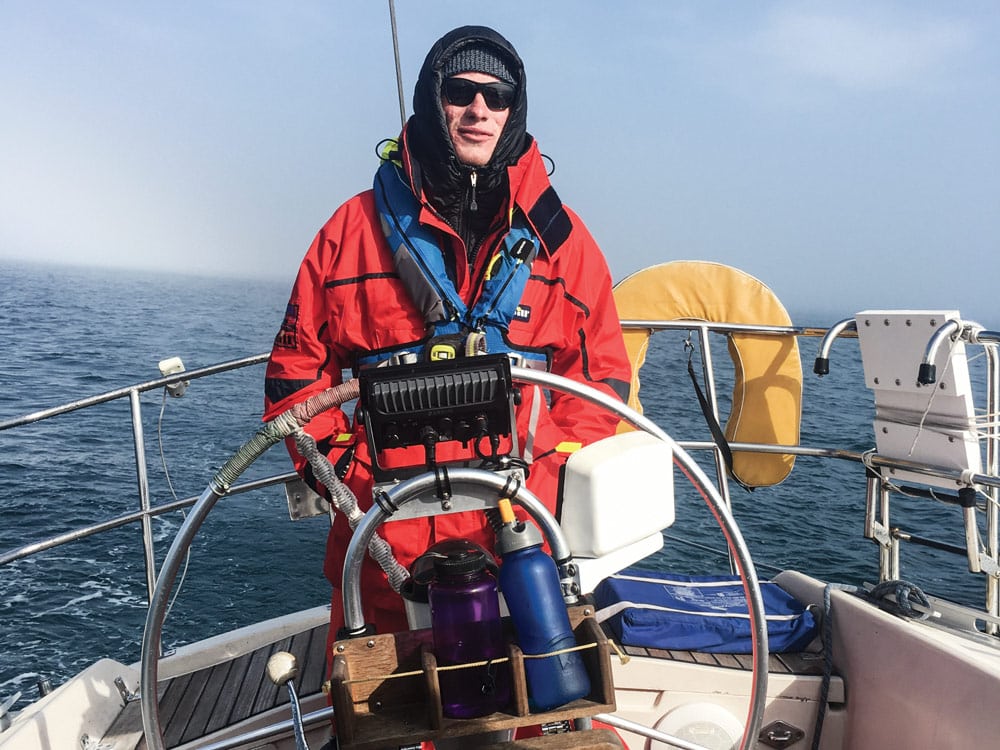

A set of larger waves slides beneath Nellie, my trusty Beneteau First 42, and one dollop of wave spanks her transom and — splash! — lands in my father’s lap. It’s a pot-full of cold ocean, but on this day, it makes Ted grin. “Rub a dub dub!” he chortles. My nephew Mac responds from the wheel, “Three men in a tub!” and we smile to recognize ourselves in this building sea.

Yes, it’s the three of us aboard this tub, and from my nephew to me to my dad, it’s three perspectives on an ocean experience. You see, the old man’s been remembering the whales he saw 50 years back and the shoals of fish he sailed through when he was young. But Mac says he’s seen mostly jellyfish in his sailing, and rarely a whale. In other words, my crew combines past and future into a crucial ecological present: Ted McCarthy is into his eighth decade afloat, Mac Huffard is getting ready for college with two weeks at sea, and I’m somewhere between the kid my dad took sailing and the skipper my nephew knows.

The Gulf of Maine is changing around us in increments we register over a lifetime but overlook in any single season. Its illustrious fishing history has been on my mind this whole cruise, and sharing the cockpit with family born in 1941 and in 1999 gives me a new appreciation for the slow changes each generation lives through in any ecological community. Cape Sable is just ahead, and it occurs to me we’re rushing along atop the Gulf of Maine as an ecosystem, as a historical context and as a family setting.

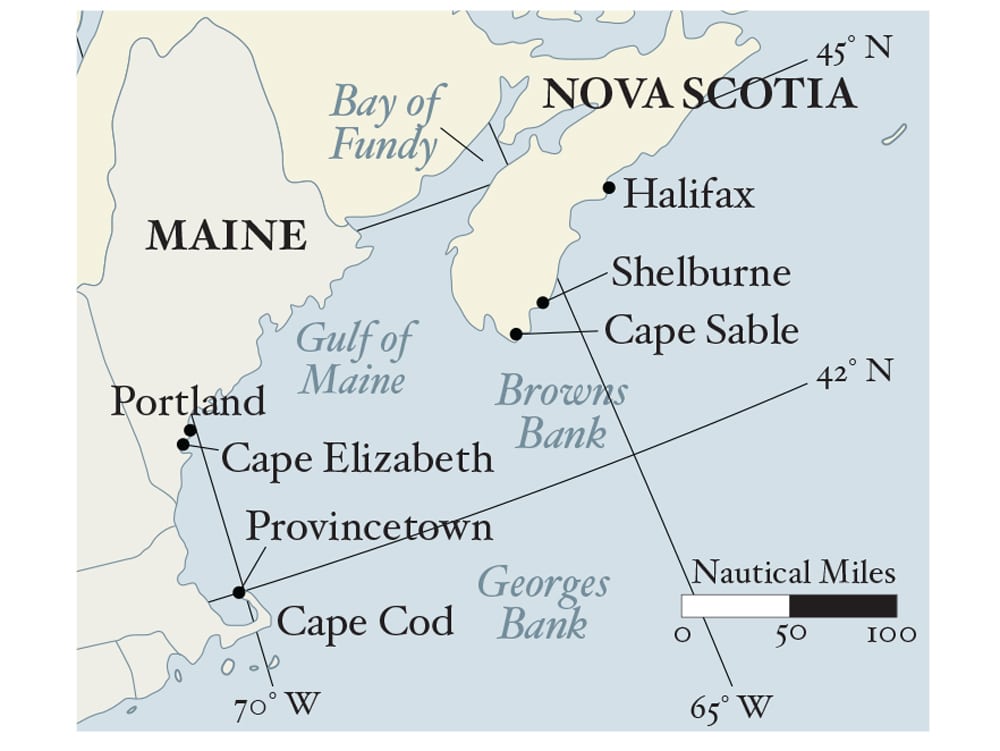

The summer goal was pretty simple: first, cruise from Cape Elizabeth, Maine, to Cape Sable across the Gulf of Maine’s celebrated fishing banks; second, visit eastern Nova Scotia; third, get back around Cape Sable and return to Maine on the shorter leg across the Bay of Fundy. The first leg was about 300 miles, with the promise our keel would pass over fish-rich Browns Bank and Jeffreys Bank and other shallows that arc from Cape Cod all the way to the Grand Banks. We weren’t going all the way to Newfoundland — I only had three weeks — but I was excited this little venture would combine marine ecology and family to truly appreciate the Gulf of Maine.

The area from Cape Cod to Nova Scotia is the Gulf of Maine: 70,000 square miles of life as deep as the Empire State Building and as cold as the refrigerator in your kitchen. If someone asks where I’m from, I say “Maine,” but I’d probably do better to say “the Gulf of Maine.” That second answer would emphasize coastline and islands quilted with spruce and known to heron and osprey. The prevailing winds blow from southwest to northeast, from Cape Cod’s glossy tip to the matte-gray breakers off Cape Sable, a journey of 300 miles, if run by sailboats in the Marblehead to Halifax Ocean Race. It’s no surprise these racers encounter a living ocean’s emissaries in that rich expanse of currents and banks. Out there are fin whales, right whales, humpbacks and sharks. Maybe you’ve been, and out there you saw terns, gannets, gulls and storm petrels. Of course, amid these visitors to the surface are hints of deeper play from mackerel, herring, haddock and hake.

Aboard Nellie, the crew accommodates my enthusiasm for the lives and ledges 50 fathoms beneath our deck shoes. My nephew should care that right here in his family’s front yard is one of Earth’s miracles of abundance. Sandy shallows like Browns Bank separate the warm Gulf Stream from the cold Gulf of Maine, and tidal streams mingle nutrients that power spectacular plankton blooms, feeding the herring that feed the cod that bring the tuna and swordfish and sharks and whales. But when you’re 19, ecological history seems less important than the social present. Nevertheless, on this family cruise I try to impress that we follow enterprising fishermen who knew these banks before there was a United States or a diesel engine.

A mile ahead of us, a white hull steams east below whirling radar domes and scything antennas. I say, “Imagine it’s 1575. You’re sailing here from Cornwall or Brittany with a simple compass and a couple of prayers. Those people were adventurous.” The crew nods, wary of my enthusiasm for the historical. Today’s fishermen have my respect too, and in a sense, the fishing is the story. The fishing brought Europeans in their shallops and pinnaces, and even the longboats of Leif Erikson back in the year 1000. Erikson, they say, settled Vinland (what’s now Newfoundland), and on the foggy rollers off Matinicus you can imagine the squeal of those oars.

If wanderlust brought the Norsemen, cod brought Portuguese, French and English fishermen. Those were in the Cabot, Hudson and de Champlain days; fat-bottomed fishing boats rollicked in Maine harbors before Jamestown or Plymouth Plantation even existed. On the Isles of Shoals, at Popham Beach, up on Monhegan, men who might have drunk with Shakespeare and fired on the Spanish Armada dried their fish on New World racks, pulled their nets near Wabanaki families and, each autumn, packed their holds to sail protein back to a hungry Europe.

But where are the fish these earlier generations applauded? I’m listening through the hull to hear the Gulf of Maine’s gentle testimony — there’s a cautionary tale unfolding. Sailing from Cape Elizabeth to Cape Sable buys you a front-row seat to contemplate the plenty this gulf once held, and a view of what loss looks like at the ecosystem level. The marine life I encountered today — gannets, guillemots and terns in the air, a whale at some distance, a shoal of bluefish to port shepherded by five gulls — is a fraction of the vibrant communities that once interacted here. Early visitors left clear written records of their days. In 1602, John Brereton described: “Whales and Seales in great abundance … Tunneys, Anchoves, Bonits, Salmons, Lobsters, Oisters having Pearle, and infinite other sorts of fish, which are more plentifull upon those coasts of America, than in any other part of the known world.”

“More plentifull,” indeed. A dozen generations back, our ancestors reported walruses off Nova Scotia, beluga whales all the way to Boston, great auk in the thousands, salmon runs to push a rowboat upriver, right whales aplenty and, above all, the majesty of cod.

Looking out for fishing boats, I tell Mac it was the limitless regenerative power of cod that bankrolled early America. Cod are the perfect inhabitants for these perfect waters, feeding on the sand lance and capelin and other tiny denizens of the shallow banks nearby. Around 1740, rich men in the Massachusetts State House hung a wooden codfish above their chamber to remind themselves where wealth comes from. They called it “the sacred cod”! Today, you can barely find a codfish. By some estimates the Gulf of Maine holds only one-third of 1 percent of the cod here when the Mayflower came ashore.

My dad says he remembers boats going out of Boston and cod as cheap fish for Friday nights.

Mac says, “I’ve never seen a codfish.”

I think that if each generation normalizes the conditions it inhabits it can only presume the ecology it encounters to be “natural.” We’re trapped in a limited perspective, like boats in the fog. Maybe sailing is a useful antidote because so many of us learn to sail in family groups, and sharing a cockpit with your family’s youngest and oldest is also sharing the long view on ocean health.

Four hundred years along, Gulf of Maine cod teeter on the edge of endangered status. Industrial fishing in these waters pulled so many fish so fast that even the cod could not reproduce quickly enough to sustain their dizzying numbers. Endless supply was the assumption and endless resilience was the expectation as vigorous trawling of undersea banks like Jeffreys Ledge and Cashes Ledge dug and gouged the seafloor into a mucky morass. Powerful mechanized fleets were deployed from the 1920s on. “The combined force of decades of fishing by domestic and foreign trawl fishers stripped the bottom of life, and rearranged the very foundation of the gulf,” writes marine biologist Callum Roberts. “Trawling had become a geologic force.”

When I was a kid, more powerful fishing boats from Portland to Gloucester followed the cod offshore where they mated and shoaled, and there collected the oldest, healthiest fish in that vulnerable moment. We thought it was business as usual back in the 1970s, but factory fishing swept up the last best hope, and left us with a stunted ecosystem. I recall catching codfish on a jig off the New Meadows River, in Maine, in the mid-’70s, at a time when ecologists were warning of a collapse and the fishing industry scoffed and brought more technology to bear. That last cod I caught was green black, goggle-eyed, held firmly at the jaw by my big hook. I saw only a personal success in those fins and smells, a good fish I’d caught with my hands, and not the last twitch of a receding era.

In Nova Scotia, we tied up to fishing docks and I chatted with amiable, welcoming fishermen. They’ve adjusted their practices since the 1992 moratorium on cod fishing. “I’m mostly for the haddock when I can, and the lobsters all winter,” said one skipper in West Head. Another fisherman told me of the sustainable tuna industry off Cape Sable, where men fish hook-and-line for bluefin tuna in an enterprise free of bycatch and destruction. They all work hard to satisfy the appetite for fish ashore, and deserve our consideration.

Across the border, Maine fishermen suffered a record-low cod catch in 2015 (about 250,000 pounds), and promptly had a worse year in 2016 (170,000 pounds). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tells us the spawning population in the Gulf of Maine has never been smaller — and the overall decline since 2005 has been 80 percent. That is 80 percent from already rotten, overfished, habitat-debased 2005, not my heyday, shiny-jigging 1975, much less a robust base line such as 1575. For someone born in 1999, these fisheries seem normal; to my dad, they seem sadly depleted. I deduce that our influence unfolds at such a slow pace that profound environmental changes surprise us all — like watching the clock’s hour hand, you know it’s moving but you just can’t see it.

Another steady-slow cause of environmental harm is our hotter climate. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than just about any body of water on the planet. This warming means big changes to the ecosystem. A retired fisheries officer I interviewed said ocean warming is a threat to Nova Scotia: “You can blame Exxon or you can call it God’s wrath, but the fact is cold-water fish are going elsewhere, or not surviving.”

The cod, halibut and even lobsters are sensitive to temperature, and as the Gulf of Maine warms and as it acidifies, signature species such as lobster struggle. With spray coming aboard and Nellie fighting the helm in a trough, I wonder what this watery place will look like two decades on, when Mac takes his kids to the sea.

But it’s not all bad news. On the sail up here we glided across fishing banks on a calm day, and the flat seas were delightful with life. The cod might be all but gone, yet I saw humpback whales spouting bubbles into the setting sun, white-sided dolphins leaping clear into the air and shearwaters, storm petrels and gannets dancing against blue skies. The Gulf of Maine still thrives, still lives if we will let its residents rebound. The silly “three men in a tub” rhyme ends with the ambiguous line, “and all of them out to sea,” creating uneasiness, a sense of imminent catastrophe. But what if “out to sea” is where you want to be? Then you’re not condemned, you’re lucky to know that watery place in a personal way. That seems closer to the family experience I’m having this brisk day.

To be at sea with a young sailor is to wish for an ecological future healthier than the one I’ve occupied. Maybe with awareness and planning, the story of decline in these waters can change into one of revitalization. Mac turns the wheel and looks to windward; what blows from there is the possibility of a resilient, blooming Gulf of Maine or, sadly, a wholesale unraveling of the ecology under climate warming and aggressive industrial fishing. Which way will we steer? Which way will he steer?

The Gulf of Maine is just the place for cruising sailors to take on these questions because it hosts so much incredible sailing amid so much incredible marine life. Cruisers enjoy a direct view of ocean health, and organizations like Sailors for the Sea and Turn the Tide on Plastic attest to the sailing community’s engagement. You can only hope coming generations will know the thrill of marine creatures riding their bow waves or spouting in the distance.

A flash in the water was a chunk of driftwood. Dad says, “Your grandfather saw leatherback turtles off Cape Ann,” and I think of the creatures once neighbors and now merely memories. And here we are, three generations who care about the ocean, and each of us with our own ocean in mind. Soon we’ll drop a reef in the mainsail and send Mac forward to secure the tack, to tighten the clew, to motion from the mast while my father steers us into the wind and I crank the halyard snug. A metaphor? Sure, a metaphor of people working together for the well-being of the ship, a symbol of active cooperation guaranteeing sustainability for the craft that floats them.

Jeffrey McCarthy is director of the environmental humanities graduate program at the University of Utah.