After a seven-year absence from the Caribbean, I’m happy to report that it’s still a safe haven for unconventional people. Take, for example, the yacht designer Paul Erling Johnson, now 74 years old. He’s currently living aboard and hard aground on his coffee grounds in Carriacou, in the Grenadines.

The last few years haven’t been easy for Paul. The problem isn’t sailing or the sea, it is the land. It can be treacherous. There are hidden dangers everywhere. There has been a succession of crazy shore adventures: He recently went to sleep on a discarded sheet of plywood on the beach and became a lethal (to himself) projectile when a frisky gust of wind sent him airborne over the harbor. His own 18-foot dinghy managed to land on him at the outset of a hurricane, thrusting a piece of its stem through his right calf. More recently, in the parking lot of the local grocery store, Paul mistakenly thought that all the screaming white folks were fans of his design work, not that he was about to be run over by a truck.

“The nurses at the local emergency room are sick of seeing me,” Paul admitted ruefully during our recent visit. He put down his water glass of rum in a studied manner so he could point to the spots where various bits of boats and houses and trucks have impaled his once-bronzed body.

I was a pre-teen when the 16-year-old Paul Johnson became my hero by sailing across the Atlantic in a beat-up, 18-foot lapstrake gaffer named Venus. Even back then, in the 1960s, he had a clear vision of who he was and what he was doing. Modern yacht design was off on a wrong tangent, he believed. The lofty Marconi rig was truly good only for racing hard on the wind, something that ocean-crossing sea gypsies didn’t do very often. Why put all that strain on the rigging? Why even have backstays? Gaff-riggers were cheaper, safer, faster, and more easily repaired. They were altogether superior in every way.

A cult sprang up around him. Sure, such designers as Dick Newick, Bob Perry, Gary Hoyt, Charlie Morgan, and Jim Brown all had fans and devotees, but only Paul was The One. Suddenly, half of the traditional sailboats being built by amateurs on a shoestring budget weren’t referred to as traditional or gaffers. They were reverently called Paul Johnson designs.

Paul blended the old and the new in unique and seamless ways. He quickly embraced PVC and Airex coring materials, which gave his vessels light displacement. And his designs, sporting a very modern run aft in the buttocks lines, were fast, fast, fast off the wind.

“Sure, the Marconi rig has advantages when you’re hard on it,” he’d say, “but once you crack off a tad, the power of the gaff offers clear advantages. With a gaffer, you can harness more power more quickly, and in a safe, controllable way. You don’t have to luff up to douse or hoist. The center of gravity is low, so there’s less roll. The result can be an almost maintenance-free ocean vagabond that can stay offshore for very long periods of time for very little money.”

Back in the late 1960s, Paul said, “Most modern boats are like governments. They look good on paper, despite the fact they don’t work too well in reality.”

In the big picture, though, not many agreed. The yacht assembly lines in America and Taiwan rolled out their profitable look-alike cookie-cutter craft, with more attention paid to the sales brochure than to the hull. The IOR racer/cruiser dominated. But so what? Paul didn’t care. He refused to suffer fools gladly. He wasn’t running a popularity contest; he was designing practical, ocean-worthy boats that could put to sea and stay there.

Why should he pay attention to the quibbles of the harbor queens, the club racers, the naysayers? So what if the landlubbers thought he was totally nuts: All the better! And those few contrarian sailors who did agree with Paul Johnson became, well, disciples, if you will.

You didn’t just build a Paul Johnson design. You took up The Cause.

Dozens of Paul Johnson boats started springing up under palm trees in Bermuda, the Azores, and the Lesser Antilles. John Frith got involved with his Moon. Peter Muilenburg started Breath on St. John. Lulu Magras of St. Barts purchased Pluto. Bruce Smith glued up Woodwind. Shadrock, Cherub, and dozens of others splashed.

Suddenly, the trendiest people in the traditional world of yachts were yearning for Paul Johnson designs in wood, fiberglass, and steel. At one point, there were five new Paul Johnson designs match racing in Bermuda’s Hamilton Harbour.

And Paul fed the PR fire on many diverse levels.

National Fisherman did an in-depth article. Other publications, like Yachting Monthly, sent reporters. Paul was suitably elusive and cryptic—but not too elusive or cryptic.

Who was that rum-reeking, Shakespeare-quoting sailing madman on The Today Show in New York? Surely, that couldn’t be—wait, is that Paul Johnson on Larry King’s radio show?

“I’ve seen your boat, Paul,” said Larry King. “And I wouldn’t sail it across the Miami River!”

“And given what I know of your sailing skills,” Paul replied, “that’s very wise, Larry.”

Best of all, Paul Johnson put his money where his mouth was. One year, he sailed from England to the Caribbean, then unexpectedly received a commission there to build one of his own 42-foot Venus designs. One problem: His tools were in Jolly Ole, and winter had arrived. “Tsk, tsk,” said Paul, who then nonchalantly sailed back to England and returned to the Caribbean without comment. That made four transatlantic passages for the year, two of them made in the dead of winter, and all accomplished without damage or fuss.

“Try that with a lofty, modern IOR production boat!” he taunted any who’d listen.

No one took up the challenge.

“Heavy weather doesn’t bother me or my vessels,” Paul said. “In fact, I rather enjoy being scared. It makes one feel alive!”

How many transatlantics has Paul done?

“I can’t remember precisely,” he admits during our chat, peering down into his glass for answers. “At least 30-some, but who can say, really?”

In the day, if Paul needed money, he’d hastily dash off an oil painting or two. The rich folk would snatch them up gratefully. Renaissance man was a phrase muttered deferentially wherever Paul sailed.

The women in Paul’s life are ageless. When he was a teenager, they were in their early 20s—and they still are, 50 years later.

“The ladies are better sailors,” he contends. “They work harder and are more willing to learn. Why, just recently, I had a lovely 23-year-old deckhand for a couple of years.”

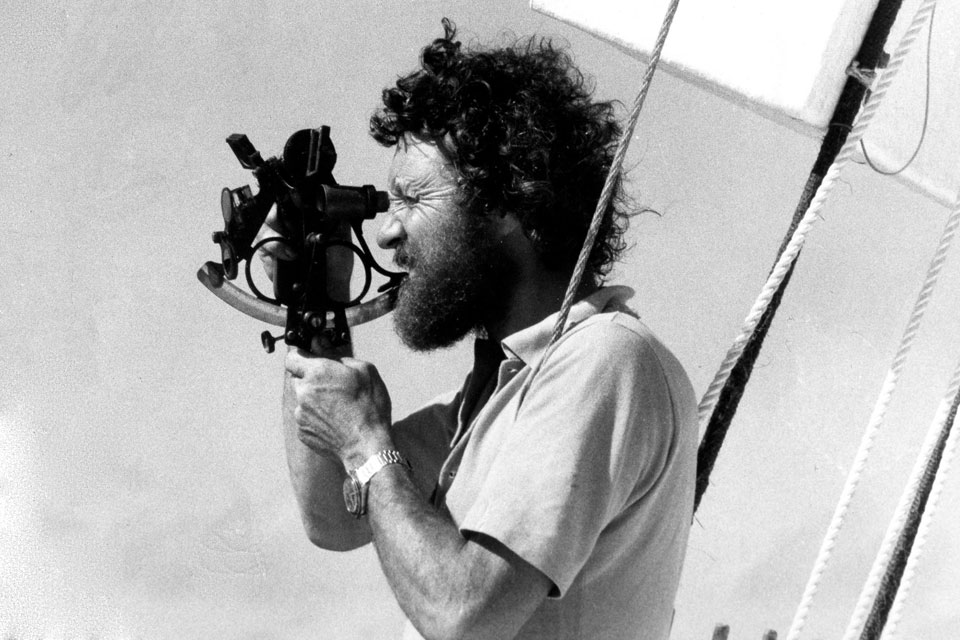

I first met Paul in the late 1970s on St. Barts. He was already a designer/builder legend. His distinctive designs were being built all over the world. He was on the cutting edge of both traditional and ultra-cheap yacht construction. He’d work all day in his cedar-scented Gustavia boat shed, surrounded by scantily clad French models draping themselves about in hopes of sensuously mixing up some epoxy for him. Then he’d retire to the famous Le Select to attempt to drink the island dry. He was as handsome as Byron: barrel-chested, wild-haired, and well-muscled. He wasn’t arrogant, precisely, just dead right, and he knew it.

In his heyday, Paul could’ve modeled for Michelangelo’s King Neptune. He had not only the physique but the mental intensity as well. A spotlight followed him around. His entourage was international: a French poet, a Spanish artist, an Italian actress, a Dutch abstractionist, a Polish violinist.

He was untamed, and his lusty appetites were enormous. People wanted to share his raw passion and to witness such classic, unbridled hedonism. A succession of Beautiful People —Lulu Magras, Mad Murphy, Jean Claude, Joe Green, Bruce Smith, Jenny May—trooped through his epoxy-splattered boat shed in Gustavia. Former girlfriends and ex-wives came and went, trailing children and divorce lawyers and other shoreside vexations. Palimony, matrimony, alimony, and plain baloney were all the same to Paul.

What did it matter what some freeway-addled stateside judge proclaimed when the Caribbean trade winds were fair and the distant horizon clear?

If there has been one big insurmountable problem in Paul’s life, it was the wicked women of his design disciples. They just didn’t seem to get it. They didn’t stay under his spell like their eager, wanderlust-smitten husbands. So these devious women continuously and quietly sniped away, pointing out the bloody obvious: Paul never grew up. He never settled down, never signed on the dotted line. Never bowed. Never stayed put. Never took the blame. Never paid—what’s the expression?—the wages of sin.

Puritans hated Paul Johnson and the strong drink in his mighty fist and the lusty song of freedom that sprung from his larger-than-life heart.

It was then that the Pacific beckoned. Yet another young lady agreed to be shanghaied. Alas, there are a lot of tiny dots in the Pacific, and some of them are very, very hard. Paul hit one. His vessel sank. But, his 18-foot dory-style dinghy was nearly as big as his original escape craft, so they piled into that for another 1,500 miles or so of Pacific fun.

Money appeared. Another vessel was whipped up, but this one didn’t last, either. It, too, slipped beneath the sea.

Today, he lives aboard one of his beloved designs in the island backwater called Carriacou. If he’s too ill to come ashore, a young, local yachtie girl heats up some leftovers and rows over. Paul then pours on the famous charm and slips in a sea yarn or two for payment.

“Is that you, Fatty?” he asks as my wife, Carolyn, and I circle his gaffer while standing on the deck of Ganesh, our 43-foot French-built ketch. “Of course I’ll come for dinner!” He keeps us laughing until the wee hours with his bawdry sea stories.

Finally he’s ready to go, but there’s one final question. “I’ve been considering sailing back across the Pond to the Azores,” he says. “Or maybe just into the lee of Tobago for the remainder of hurricane season. What you say? Which is the better choice?”

I look at the growth on his anchor rode, his sun-weary halyards, those tattered bits of baggywrinkle drooping to the deck of his nearby boat.

Yes, time has passed. Yes, none of us are quite what we once were. And yet—despite it all—there’s still fire in Paul’s belly. The horizon beckons. Why not one more grand sailing adventure?

“Both are pleasant this time of year,” I said. “I’m sure you’ll have a wonderful passage either way.”

He smiles. We’re sailors. We’re home upon the sea. Our vessels are our seashells as long as they are afloat. Screw the scolding doctors, the bean-counters, and those bloody Dirt Dwellers!

It takes him a long time to crawl into his battered dory and swing his twisted limbs into place. He coughs and clutches his chest. Finally, breathing heavily, he casts off his painter.

“I’m sure I will,” he says ever so softly as he sculls away into the inky blackness of Tyrell Bay.

Cap’n Fatty and Carolyn Goodlander are bending on a new mainsail while getting ready for another transpacific toddle.