Shift and throttle mechanisms — the cables, lever arms, clevis pins and so forth — are for the most part simple and relatively reliable. However, it takes no more than a single loose fastener, or improperly installed cotter pin, to wreak havoc on a vessel’s operation.

Several years ago, while working as a mechanic at a marina, I watched a boat owner land his 40-foot sloop on a dock in textbook fashion, coming alongside, shifting into reverse smartly and bringing the vessel to a halt. The owner then jumped onto the dock with spring line in hand, but as he prepared to make it fast to a cleat, it was pulled from his hand. The vessel, it turned out, was still in reverse, and because the rudder was still slightly over, it described a large circular path, whereupon it made contact with the dock once again and was brought under control. A similar event occurred in 2005, with far greater consequences, when a ferry in British Columbia crushed 22 boats berthed in a marina adjacent to the ferry slip as it lost control while landing. The culprit in both cases? A single failed cotter pin.

The vast majority of shift and throttle controls rely on the familiar plastic-coated wire jacket with a movable wire core. In order for this system to work properly, several criteria must be met. First, the jacket must be completely immobilized at both ends. This is typically accomplished with a U-shaped clamp mechanism, or a scissors-style hook clip; this is through-bolted to a sturdy bracket at the engine end, and to the control itself, or the binnacle or cockpit, at the other end. With the jacket stationary, movement of the shift lever causes the cable core to move smoothly. If, however, the jacket is not secure, it will move with the core, preventing the latter from telegraphing movement to the engine. The U- and hook clamps should be routinely inspected for movement and corrosion.

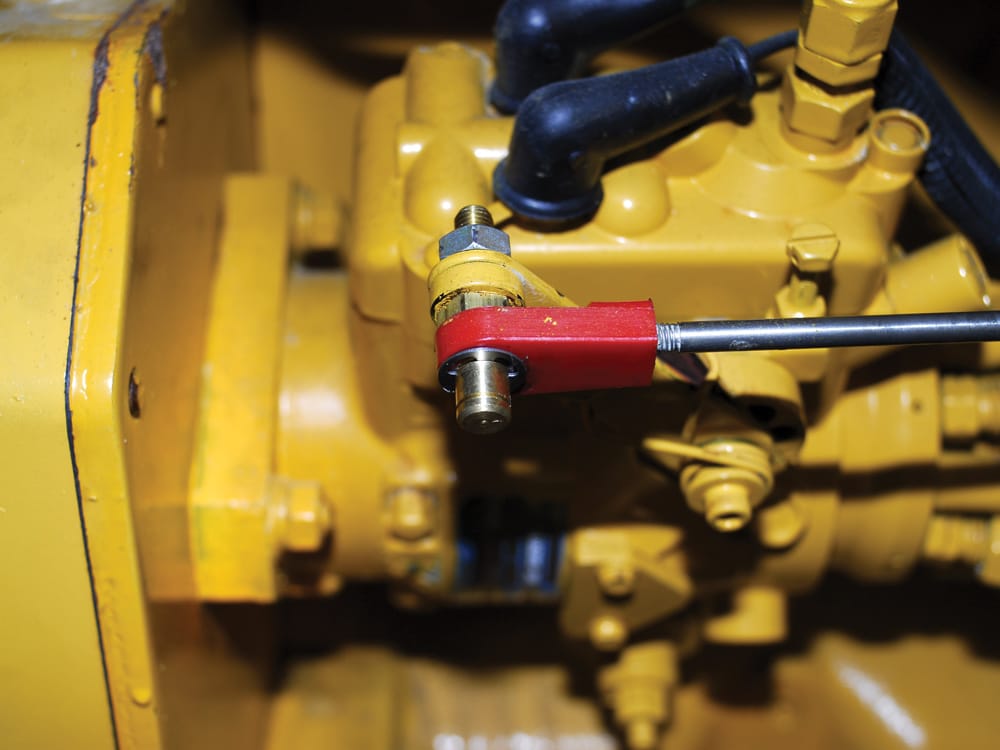

The core must be securely attached to the shift/throttle levers at the helm, as well as at the engine/transmission. This is nearly always accomplished using proprietary threaded cable adapters, which are available in a wide range of designs. The proprietary aspect is important. “Field-engineered” adapters, common nuts, or ordinary bolts and screws must never be used in this application. Only components supplied by the cable manufacturer should be relied upon to adapt cable ends to throttle controls, the transmission shift and injection-pump throttle levers.

Read Next: Engine Cooling System Maintenance

Wear is an ever-present issue where control cables and their terminals are concerned, particularly where soft metals such as brass meet hard metals such as steel. Lightly lubricating this interface will extend the life of these parts, while utilizing articulating ball ends can virtually eliminate wear altogether. In most cases, cable end terminals are plated mild steel, which means they will eventually rust if not corrosion-inhibited. Cable jackets, which are plastic, are also subject to chafe and melting if they come into contact with hot surfaces, such as exhaust manifolds. Once the jacket is pierced, moisture can enter, which will cause rust and cable seizure.

Where cotter pins are used to secure clevis pins or clevis-style terminals, a washer should be installed between the cotter pin and lever surface, and again, lubrication should be added. Cotter pins and washers should always be stainless steel.

Eye pins, an alternative to the cotter-pin arrangement, utilize gossamer and easily lost C-clips. If your system relies on these it’s best to keep a spare or two aboard. All fasteners used in control cable systems should be self-locking or utilize lock washers, and the additional use of thread-locking compound represents a belt-and-suspenders approach.

All readily accessible components in this system should be inspected at least monthly, while less accessible parts (for instance, those inside the binnacle) should be carefully reviewed at least annually, looking for rust, wear and unwanted movement.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.