I am a sailing scuba diver; one wall of my living room is painted deep “teal ocean” and hung with an enlarged photo of me diving — wearing a pink weight belt and pastel-colored regulator hoses — during a long cruising stay on Oddly Enough, our Peterson 44, at Kavieng in Papua New Guinea. But I’d never sailed or dived at Wake Island, and I’d certainly never gone down to 2,100 meters. This changed in August 2016, when I virtually joined the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s ship for ocean exploration and research, Okeanos Explorer, for an expedition that filmed the deep ocean bottom around Wake from a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). I joined it as a “citizen scientist,” watching live on my computer screen.

The Campaign to Address Pacific Monument Science, Technology and Ocean Needs, or CAPSTONE, is a three-year mission to explore deepwater marine protected areas in the central and western Pacific Ocean, initiated by NOAA and its partners. These include some of the last pristine marine ecosystems on the planet and harbor numerous protected species. Almost every dive finds previously unidentified life-forms and underwater formations such as mud volcanoes and hydrothermal vents. Wake Island’s waters are also rich in archaeological sites for ships and aircraft lost during World War II. Most deepwater areas, though poorly studied, are of high interest to federal and state agencies because of their potential resources. It has a dark side, however. Like contract archaeology, Okeanos surveys areas ripe for resource extraction to see what would be destroyed. But CAPSTONE is also intended to garner support for preserving what’s there, and for that, the bigger the public presence the better.

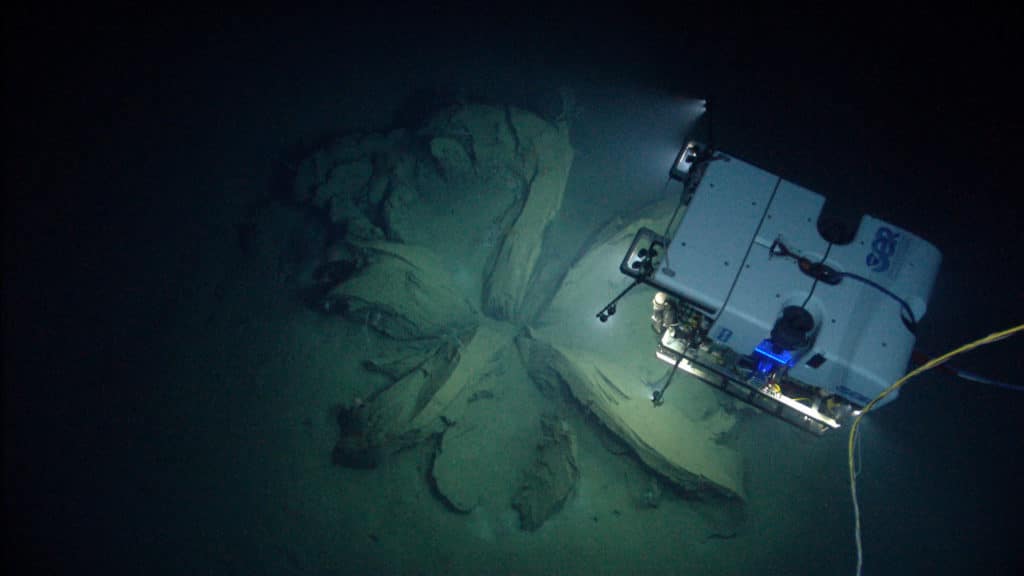

Expedition cruise legs can take three weeks, with two scientists on board Okeanos — a geology lead and a biology lead — plus crews to run the ship and two ROVs: Deep Discoverer (D2), with a fabulous video camera that films high-definition close-ups of stuff I wouldn’t notice diving, and Seirios, which goes down on a separate cable and hovers above, filming D2 and the surrounding ocean floor, which it lights up for perhaps the first time ever. Dive and mapping operations are streamed live, so every day this past year from mid-July to August, at about 4:30 p.m. (8:30 a.m. Fiji time), I’d think about settling in to watch.

In the Okeanos digital control room, the scientists observe and record the dive and the ROV crew operates its vehicles — including the mechanical arm that collects samples — guided by computer screens. Besides a livestream of what is seen and heard on the NOAA website, there is a large online chat room of scientists and others on voice call to help identify the sea creatures and rock formations. For all its seriousness, it’s also a show; each leg has different science leads who set the tone, and their interpersonal chemistry shapes the time we spend together. On the Wake Island leg, Chris Kelley and Jasper Konter, both of the University of Hawaii, are classic science nerds. They love their chosen fields, they love awful jokes (especially about fish) and their laughter livens the Internet.

Wake Island, 1,500 miles from Guam and 2,400 miles from Hawaii, was first discovered by Europeans in 1568, when Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña de Neyra visited the atoll. At 19° 16’ N, 166° 38’ E, it’s an occasional stopover for cruising sailboats heading across the northern Pacific. A boat basin inside the pass houses support vessels for the U.S. Air Force, which runs the island. There is a narrow reef shelf on the ocean side of the pass suitable for sailboat anchoring, but overnight is generally all that’s done.

The Wake Island voyage ended after diving and mapping isolated seamounts on its track from Guam to Wake to Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands. In September, Okeanos docked in Hawaii and offloaded specimens of life and rock it collected over the year like Noah’s ark traveling the sea. Voyages in 2017 include the Howland and Baker unit of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument and the Phoenix Islands Protected Area. If you’ve ever wondered what might be lurking below while cruising the Pacific, join Okeanos here for a peek at the magnificent deep underwater world. — Ann Hoffner