There’s always a feeling of excitement mixed with a twinge of anxiety as the mooring pendant drops, or the anchor is catted, and a voyage begins. What do they say? The thrill in adventure is just this side of terror.

This time, it was the Friday before Easter. Any savvy sailor knows that you never begin a voyage on a Friday, not even on Good Friday.

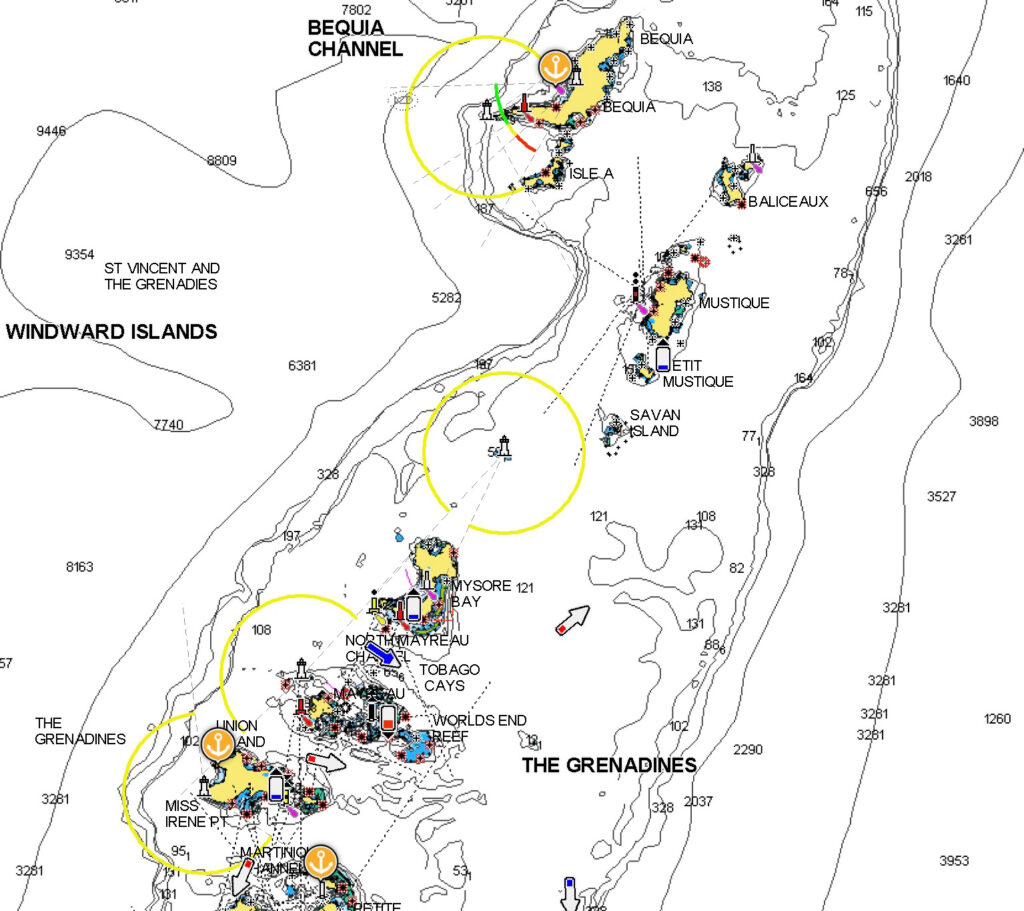

Our plan was for a quick hop from Bequia down to the Tobago Cays, then to clear customs at Union Island, and then to head to nearby Carriacou. We wanted to visit the shipwrights who still build wooden boats the old way. We would begin our real voyage northward, up through the Lesser Antilles, the following week.

The wind was light as we headed out of Bequia’s Admiralty Bay and motored past Moonhole, an abandoned villa carved into the cliffs along the bay’s southern rampart. We rounded Western Cay with the dinghy tagging along behind and headed south-southwest, aiming for the island of Canouan. This string of islands in St. Vincent and the Grenadines stretches for 30 miles and has a lot going for it. The islands are all within sight of one another, all within an easy beam reach, and each different, with anchorages, communities ashore and great diving. It’s a smaller version of the British Virgin Islands.

I consulted my copy of Chris Doyle’s Guide to the Windward Islands as a lazy swell came from the east, barely noticeable on the calm, flat sea. With the sails rolled up and the autopilot set, the boat’s owner and I settled into the cockpit for the two-hour passage to Canouan.

Lounging there in the cockpit, under the dodger and Bimini top, I found much to like about this 30-year-old yacht. It was quality-built, with a lot of thought put into the design. Handholds were where you wanted them; the push-pit surrounded the cockpit; stout stainless steel rails extended forward to midship; and 30-inch-high lifelines ran forward from there. The decks were uncomplicated. The anchor platform on the bow was well planned. There was a good-size windlass with a chain break. A single bow roller housed the Rocna anchor. There was room on the foredeck to strap down the dinghy offshore.

I was happy to be aboard as Bequia dropped astern and two small islands appeared 2 miles off to port: Petit Nevis and Isle à Quatre. On the horizon, 5 miles farther east, was Mustique, a hideaway for royalty and the jet set. (Neither of us were appropriately attired for a visit.) Ahead, Canouan was visible, and beyond that, the rugged peaks of Union Island, looking like a gateway to Jurassic Park, only 24 miles away.

Canouan was one of the poorest islands in the Caribbean when I anchored there 15 years ago. Then, hotel developers expanded the airport to accommodate private jets. The residents now have a slightly higher standard of living. Grand Bay is the main harbor and anchorage, but we kept going.

Back in 2010, my family and I spent an overnight near here. It was a night to remember. We had anchored in 16 feet of water, off the Tamarind Beach Hotel’s dock near The Moorings charter base. The wind began to whistle down through the valleys. Gusts were heeling our 57-foot ketch. I had 100 feet of chin out on a 70-pound Bruce, but we were creeping ever closer to a catamaran anchored astern.

I got the kids (then 9 and 11) out of bed to help. The spare bow anchor was a 45-pound Danforth on 30 feet of chain and 200 feet of five-eighths nylon rode. While I brought the RIB around to the bow, the kids untied the Danforth and pulled out the chain and rode from below. They lowered the Danforth over the bow rollers as I guided it into the dink and then motored out 100 feet or more, with the kids paying out the line. Eventually, I slipped the anchor over the side—none of that anchor-throwing stuff for me.

Back aboard, we took in the rode until the anchor chain was slack. The kids were too excited to sleep, as was I. Throughout the night, the wind plucked out a tune in the boat’s rigging.

I thought about that memory as my current ride, Striker, rounded Canouan’s west end. We headed for the next small island, Mayreau, 4 miles away. On its northern tip is a perfect little anchorage, Salt Whistle Bay (more of a cove, really). Its palm-fringed beach and scattering of bars and restaurants make it too popular for those looking to get away from the crowd.

We were heading for an even more magical spot in the Tobago Cays. As we approached, I went forward and sat on the pulpit to watch the water change from deep, offshore blue to pale, with the seabed visible 30 feet below. The pale blue nearly changed to white as we approached the beach. Brown patches denoted coral heads and reefs. This was one lovely and lonely piece of the Caribbean, with only an open sea to the horizon in the distance.

It was late March with the season drawing to a close, but there were two powerboats and a dozen or more sailboats anchored. When I had last come through, it was late January with dozens of boats and beaches full of people.

My preference would be to anchor off the beach at Petit St. Vincent, a private resort that’s far from the crowds, yet within a short dinghy ride to excellent snorkeling. We passed Palm Island, with its resort and villas, and ended up in Clifton Harbor. I had been here a few times, including in 2010 after a month in Grenada.

Back then, we had planned to stop at Union Island for the night. While looking for a spot to anchor, a helpful West Indian chap had come along side in his pirogue, inquiring if we needed a mooring.

“How much?” I asked.

“100 EC.” About $60.

“Too much. We’ll anchor. Thank you, though.”

My new friend was persistent, and we settled for about $30.

“Where?” I asked.

“Follow me.”

He led us to a mooring right in front of the yacht club’s pier. How convenient. I gave him the fee, thanked him, and off he went in his colorful fishing boat. My family climbed into our RIB and went ashore to clear in.

Back on board that afternoon, as I was settling in with a rum and tonic, a day-charter catamaran approached with a woman on the bow. She shouted for us to get off the mooring. My kids ran forward to drop our mooring line as I started the engine, and we circled the harbor, searching for a spot to anchor. By the time our boat was secure, I was fuming.

I spied the pirogue tied to the fishermen’s dock, jumped into our RIB and sped ashore.

“I think he’s at his mother’s place,” an elderly chap told me. “Here, Bert will take you.”

I climbed into a nearby taxi. Off we went—first to his mother’s house, then to his wife’s, then to his girlfriend’s and, finally, back to the pier. My “friend” was waiting. He handed me a $100 EC bill.

“You got change?” he asked.

I ignored him and headed for my dinghy. He followed. We climbed into our respective boats. He circled our sailboat. My kids hid behind the staysail bag on the foredeck while I argued the taxi fare, the illegal mooring rental, and the unfairness of it all.

After a while, he realized I wasn’t going to give him the money. He left. I lay awake in the cockpit most of the night, fearing retaliation.

But back to today.

This time, as we passed the harbor entrance buoy, a pirogue with two teenage boys roared up along the side. The taller boy at the engine yelled: “Do you want a mooring?”

“How much?”

“For you, I give you a discount. Usually $150EC. Today, it’s $100.”

“Too much,” I replied.

He lowered his price.

“Done. Now where?”

“Follow me.”

They led us to a sorry-looking buoy with an encrusted pendant. We passed one of our lines through the eye of the foul-looking thing. I paid the boys and they took off.

Not trusting the mooring, I donned a mask and snorkel. I swam down the mooring line to the bottom, where it disappeared into the mud. It looked as if it had been there for a century.

We dinghied ashore, tied up at the yacht club, and walk into town, through a bazaar of colorful awnings, umbrellas and tents above everything from jewelry, bikinis and vegetables to artwork and fruit.

We couldn’t resist the two-story Tipsy Turtle. We tucked into a booth on the upstairs porch, ordered rum punches, and surveyed the scene below.

Tomorrow, we would hop over to Carriacou and clear in.

We could see it from where we sat—only half a day from Bequia, yet in another world.