aebillulstration368

A man, a plan, a canal-Panama. A man, a plan, a canal-Panama. A man, a plan, a canal-Panama. All night long, those words kept chugging though my head to the engine’s monotonous, rumbling beat. Over and over, until another palindrome relieved my numbing brain: Go hang a salami; I’m a lasagna hog. Go hang a salami; I’m a lasagna hog.

It was the wee hours of November 7, 2007-20 years to the day since I pulled into New York harbor after my Big Trip, the solo circumnavigation that had inspired me to now introduce my boys to the sea. We were doing an overnight motor from the San Blas islands to Panama, where it looked like Shangri-La, my 36-footer, would have to be quickly hauled out, yet again, to replace a shaft seal. I’d figured out how to send e-mail through the SSB, so the new seal had been ordered from the San Blas and, I hoped, was awaiting me at the Panama Canal Yacht Club.

This short leg was a coastal trip, and because the autopilot had just died, we were taking turns hand steering. I can’t sleep when close to a coastline, so I was doing most of it. Standing in the cockpit on vibrating feet, controlling the tiller between my legs, I stared at the compass light, at the shore lights to port, at the overtaking dark skies and lightning astern. A man, a plan, a canal-Panama. We droned along; the kids and Grandpa slept soundly below. Every so often I’d break the hypnotic trance with a quick look down through the companionway at the temperature gauge. Then a new thought would make an appearance, get pulled apart, and examined. Take that shaft seal-I’d read up on it and analyzed the situation until its replacement and another haulout had become the only way of looking at it anymore.

That is, the only way of looking at it for me. Grandpa, of course, between chapters of his books and visits to the wine cellar-a locker beneath the galley stove-said I was overreacting; he said that if it were his call, he’d just live with the leaking shaft. But he often claimed I was a worrywart. We’d come full circle. He was the one who’d sent me off at 18 to sail alone around the world for the sole purpose of-as he loved to tell anyone who’d listen and who hadn’t already heard it a thousand times-getting me off my butt. Now I was doing too much, he said; he chided me for being frivolous when I insisted on getting rid of a second CQR that was broken and buying a secondhand Bruce. Just use the CQR, he said. He reminded me of his credentials: four boats owned and four successful Atlantic crossings underscore that fact that he knows what he’s talking about.

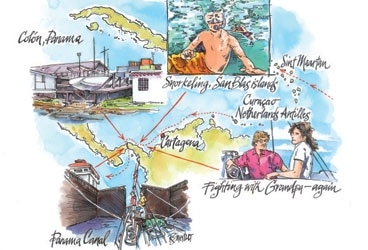

Well, Shangri-La is only my second boat, and the original plan was for me to buy her, get her up and running, then sail with the boys, 16-year-old Nicholas and 13-year-old Sam, from Curaçao, in the Netherlands Antilles, to Tahiti, in French Polynesia. From there, their father would sail with them to Australia. Then my father would bring Shangri-La across the Indian Ocean to South Africa. Finally, I’d sail her across the Atlantic to sell in Sint Maarten, in the Caribbean, the departure point of our odyssey.

To acquaint my father with the boat before his trip with her, I’d invited him to do the first leg with us, from Curaçao to Colombia. Because his only worry is about becoming a boring person, he couldn’t turn down the offer. Then he ended up staying with us beyond Colombia. Even though we were driving each other nuts, for me, the making of this memory for him, for the boys, and even for myself felt much more important than petty father/daughter grievances. For him, he’d gladly suffer my dictatorship because a sail to the San Blas islands and a Panama Canal transit with his captain-daughter and two grandsons on their grand adventure was even better story fodder.

Ah, three generations on a 36-foot boat! For six weeks I straddled my family’s past and future, whose avatars kept asking me what’s for breakfast and dinner. Initially, I’d figured I could rely on Grandpa’s help and co-captainship, but I’d turned into a singlehanded captain because he was an old dog who couldn’t be bothered learning new tricks. He’d done fine thus far without ever having had a boss, and he wasn’t going to start now letting his daughter tell him what to do, thank you very much. Set in his ways and wrapped up in his cabooseless trains of thought about the past, he alternated between telling me how he did things on his boats and-when I chose to do things my way-peevishly retiring to his cabin with a book and another glass of wine to wait for me to assign tasks because, after all, I-not he-was captain.

The kids thought that his double standards, constant challenges, and inconsistencies were hysterical and that the arguments he provoked over them priceless, and they asked me to be less impatient. I tried-whenever I wasn’t wishing that he weren’t so toughly competitive and were more agreeably cuddly. The fact was that he could be perpetually annoyed with me, but I couldn’t reciprocate. I didn’t have time. There were leaks to fix, filters to change, lines to coil, hair to sweep up, dishes to clean, a boat to steer through the night to Panama. I wondered how the mood aboard would change when he left. Go hang a salami; I’m a lasagna hog.

Officially, the trip began in Curaçao on October 13. We left there after we’d applied a fresh coat of antifouling; fixed the wind generator; installed the new Monitor self-steering and a fridge; bought and measured out new anchor chain; fixed a small leak in the most inaccessible part of the boat, at the back of the engine compartment behind the hot-water tank; changed the gaskets and seals on all the pumps; hooked up a water filter; and completed a thousand other tasks, including one more trip back to the States for me to do a couple of lectures while the kids and Grandpa settled in on Shangri-La and explored the island. It was a perfect downwind sail: four days and 480 trouble-free miles west to Cartagena, Colombia.

While Grandpa kept insisting that he never rigidly secured any of his spinnaker poles from three points with uphauls and downhauls, the boys stood their first watches and were quick studies. By Day Three, when the wind veered, Nicholas was on the foredeck, helping me jibe the pole and downhauls, and when the wind strengthened, Sam helped reef the main and furl the genoa. To my enormous relief, neither boy got sick, appetites were strong, and aside from a couple of darker and homesick 13-year-old moments from Sam -“You mean I have to be on this stupid boat for 289 more days?”-they were adjusting well.

October is the rainiest month in Cartagena, and we spent 10 wet days there learning how to use Skype, the Internet telephoning software, then calling everyone back home for pennies so we could tell Grandpa stories. We forged ahead with writing and homeschooling schedules, toured the old walled city, visited local restaurants and supermarkets, and made a daytrip to a volcanic mud bath. When the sun peeked out, Grandpa painted some rust spots on deck and fixed a leaky hatch, grousing about the overkill of my three-step method, and the boys took breaks from the books to use the pool of some friends we’d made.

I spent time with an English couple up the dock with whom I honed my SailMail skills, successfully sending and receiving my first e-mail messages and getting weather reports on the SSB. It was via the SSB that I also discovered the dripping “dripless” shaft seal. Some said it was normal; the manufacturer said it wasn’t. I ordered a spare seal sent to Panama while we waited for the southwest winds to veer back north.

Days passed with no changes predicted from one five-day forecast to the next. We simply didn’t have weeks to spare. Finally, I decided we’d tack our way to the turquoise water, langoustes, and sandy, coconut palm-topped islets of the San Blas, where we could swim and snorkel. With contrary winds, we left Cartagena. How bad could it be?

Well, it was a 187-mile passage as the crow flies, and it took us four days. Not only did we end up fighting the wind; the countercurrent was also formidable. While the ship log registered four to five knots through the water, the GPS showed two to three knots over the ground, with the current relentlessly pushing us away from where we wanted to go.

Surrounded by sandy islets and barrier reefs, we spent a week in the San Blas, a place of beautiful waters rippling over sandy ground. It was what I’d dreamed of showing my boys, and it was just what they needed after their first upwind, head-banging, heeled-over slog. They thrived. In the mornings, we drifted around an anchor set in white sand beneath the clearest of water. While I’d fix something, try to write, or take dinner orders, the kids- lithe and tanned-plowed on with their schoolwork.

Afternoons, I proudly watched my handsome lads dinghy out to the reef, drop anchor, and jump in to snorkel, gather shells, and hunt langoustes as if they’d spent their lives doing so, while Grandpa napped, read, mixed drinks, and took pictures. By each evening, the boys had turned into prunes with feet blistered from their fins.

One day, during an engine check, I discovered a pile of shavings accumulated beneath the shaft seal. The bearing had started breaking down, and the drip had become a minor gush. I started reading and rereading one of Nigel Calder’s books on shafts, stuffing boxes, and seals, and I consulted the manufacturer via SailMail. To replace the piece meant uncoupling the shaft from the transmission and sliding it astern far enough to remove the old seal and slide on the new one. It sounded like a haulout job in Panama-a worrisome thought made worse by the electrics that started acting up next.

So I read Calder’s chapters on batteries, regulators, monitors, alternators, and wiring and got a terrible headache. Fortunately, I made friends with another cruising couple anchored nearby. They’d been out for years, along the way fixing and maintaining a similar electrical system on their boat, and they helped me figure out how to reset the interface monitor and alternator regulator, two bits of equipment completely alien to me. In the process, I also cleaned connections and traced all kinds of wiring-that previously had been a big mystery of spaghetti-to their functions and sources. The boys wanted to stay in the San Blas forever, but we needed to get the shaft-seal problem sorted out, transit the Canal, and cross the Pacific before my five months with them came to an end. Their father was meeting us and taking over in Tahiti at the end of February; I had only 115 days left with them, and time was limited. Ever since I’d bought Shangri-La, every little setback felt urgent, like a time sink standing between me and my ability to relax until it was sorted out. When I was very young, I’d learned the hard way all about fast-paced schedules at sea, about relaxing now and paying later. I was trying my best to do things right this time and earn credit toward some trouble-free cruising time in the Marquesas.

The responsibility of pulling this whole trip together weighed a ton, and I was looking forward to reliving the best sailing memory from my entire circumnavigation: the downwind Pacific crossing to the Marquesas Islands, the one I’d been describing for years as my most perfect ever, with dolphin and whale escorts and beautiful sunrises following spectacular sunsets. I craved the simplicity of days when decisions would be based on what the sea and wind told us to do, forcing us to slow down, dream, and think. No more equipment to buy, people to call, repairs to make that couldn’t be done with what we had on board. Just us, slowly wending our way across the great ocean void, to make landfall on Fatu Hiva, the most beautiful island I’d ever seen.

We did what we could with our days in the San Blas. I snorkeled with the boys, got a sunburn, showed them a sea cucumber, and watched how they stalked and captured their langoustes. The Kuna came paddling by in their dugout canoes and sold us molas, oranges, and coconuts. One Kuna offered to run errands to the mainland. Nicholas gave him his new machete to have it sharpened on a grinder, but it never came back before we left. That’s because we weren’t really cruisers; we were fast-trackers, and we didn’t have days to wait. A man, a plan, a canal-Panama.

We had a date with a shaft seal, so one beautiful Tuesday morning we stowed the dinghy, turned on the engine, hauled up the anchor, and left. As we pulled out, Sam said he was beginning to understand how fast 289 days could zoom by. The boys were already down to something like 267. That night, he cooked us dinner-spaghetti with red sauce-and Nicholas did the dishes before they went to sleep on the saloon settees. I kept steering along the Panamanian coast while the engine rumbled. The twinkling lights ashore were soon obscured by the thunder, lightning, and rain that finally overtook my little family craft.

Big ships heading to and from the Canal appeared and disappeared behind blanketing squall lines. Below the closed companionway, the kids and Grandpa still slept. I was hunkered down in rain gear, my eyes frozen on the southwest compass course. I visualized it swinging west with the wind at our back, with another distant landfall of frangipani, hibiscus, French baguettes, and swaying South Pacific island music beckoning. The shaft seal would get replaced, the Canal would get transited, and before we knew it, we’d be headed for the Marquesas, which, provided our passage was nice and fast, would be the next paradise where this mass in motion could drop anchor and stay for a while. I stretched and readjusted the tiller to another friction point between my legs. I hoped that by then, we’d have slowed down and relaxed enough to have gotten A man, a plan, a canal-Panama out of my head.

In 1987, Tania Aebi became the youngest woman to complete a solo circumnavigation. Today, she’s a writer and lecturer who runs sailing flotillas and lives with her family in Vermont.

To read more about Tania see “A Year of Momentous Decisions” from our December 2007 issue