It was to be a routine delivery: bringing my boat home from the Mediterranean, sailing from Tunisia up along the west coast of Italy to Genoa, where I would put Ranger on a freighter to Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

But it turned out to be a journey of discovery. A sail into the past, along a landscape so choked with beauty and bounty, hazards real and imagined, ancient myths and contemporary events, all amid rolling seas and emotions. Five knots was too fast to absorb it. Only now, years later, have I found the storyline.

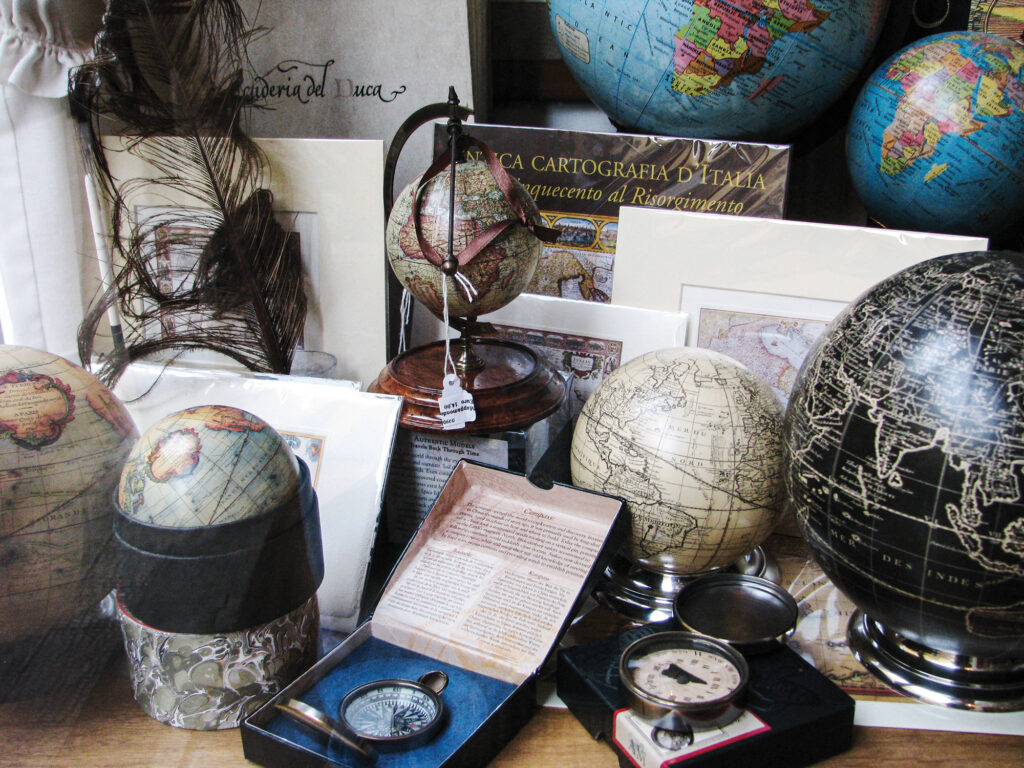

In 800 miles, I traveled through 2,000 years of marine navigation, from a continent once skirted by Phoenicians who lit fires as waypoints, to the creation of nautical charts and compass wayfaring, to explorations of the entire world. It was all capped, in the 1980s, with the invention of electronic charts.

On a rhumb line, Genoa lay 500 miles to the north. Pushing my 1970 Allied Seabreeze yawl, I could have motorsailed it in five days. But to pass by the Italian coast would have been a crime punishable by regret. I set aside two months and invited three mates to join me for successive segments.

The first was Wally Wallace, a burly, fearless Vietnam War paratrooper. First mate on my 2002 trans-Atlantic, he’d become a sought-after delivery captain and cook on Maine tourist boats. I knew that he would save me if Ranger were to founder. He met me in Tunisia at Yasmine Hammamet, an upscale, French-owned resort and marina where I had left the boat, and began to tackle a list of jobs created by three years of Saharan sun and dust. We were getting to know Ranger again, including her dripping “dripless” shaft seal that periodically lit up the bilge-pump light. My log is filled with expletives from each time it spiked my blood pressure.

Once we had cleared customs with a 40 dinar ($13) baksheesh bribe, we found ourselves in waters divided by culture and wealth. There were Muslim shores where fishermen still plied hand-hewn sailboats, and where Africans trying to escape died trying. There was the “North” of wealth and opportunity. Hammamet was used by large-yacht owners to sail through European Union loopholes. By visiting Tunisia for a couple of nights every two years, they avoided a 20 percent tax on the boat’s value. The cost of fuel for the round-trip from their home ports in Europe—thousands of dollars—was worth every penny to them.

The night before our departure in March 2012, a cold Sahara wind whistled through a thousand shrouds. Little did we know that 100 miles away, two boats carrying sub-Sahara Africans were wallowing toward the Italian island of Lampedusa, where they’d hoped to find asylum. One boat with 50 souls landed the next day. The other, with 60 people including two pregnant women, was found in distress a few days later, with five passengers dead.

As that tragedy unfolded, Wally and I were motorsailing toward Trapani on the toe of Sicily, 150 miles and a First World away. There, we enjoyed a beer and baked redfish that Wally caught en route. From Sicily, under jib and jigger, we made 6 knots bearing 31 degrees across a lumpy Tyrrhenian Sea, marked by mythic wakes of Odysseus. In his famous book, Homer had left a spaghetti snarl of supposed routes and infamous dangers.

“It would be tempting to treat the Odyssey as a Baedeker’s guide to the Mediterranean,” writes David Abulafia, the dean of Mediterranean scholars. Alas, he added, “the map of the Mediterranean was infinitely malleable in the hands of the poets.”

That said, Homer got one thing right: The Med is tempestuous. During our 180-mile sail across the northern border of the “Aeolian triangle,” named for the bag of wind given to Odysseus by Aeolus, Wally was kept busy changing sails.

The welcome sight of Amalfi on the Italian mainland is reflected in my log’s tally of our landfall celebration: pizza, beer, pie, internet, ice cream. A stroll through the colorful waterfront, devoted now to tourists and old men telling old stories, provides just a hint at Amalfi’s maritime significance. Although a bronze statue of hooded Flavio Gioia stakes the claim that he invented the magnetic compass here in 1302, it too is a myth. Centuries before, the Chinese had discovered the magic properties of lodestone, a rock that, if hung on a thread, points north and south.

Still, behind the legend is a true history of Amalfi as an international port, a wealthy city-state based on trade fostered by the compass. For 600 years in the Middle Ages, Amalfi merchants turned the Mediterranean into a bazaar, trading Italian wheat, timber, linen, wine, fruits, and nuts with Tunisia and Egypt for oil, wax, spices, and gold.

Paper charts, drawn by exploring sailors, stimulated more trade. Italy, and the whole Mediterranean, shows up on maps as early as 500 B.C. The Romans mapped their empire, in part to mark their conquests. While Columbus sailed “for gold, god and glory,” the Med was mapped for one reason: money. Amalfi’s prominence vanished with an earthquake and tsunami that destroyed the port on November 25, 1343.

Portolan charts, an Italian term for detailed port maps, were in use by 1270. “The outline they gave for the Mediterranean was amazingly accurate,” writes Tony Campbell in The History of Cartography. The work of the first named practitioner, Pietro Vesconte of Genoa, who died in 1330, “was so accurate that the Mediterranean outlines would not be improved until the 18th century.”

Leaving Amalfi, sailing southwest along the Sorrento Peninsula, we lacked the wardrobe and class to rub shoulders with the glitterati on the island of Capri. Instead, we created our own photo ops amid the rocks and tunnels and cliffs of Faraglioni at the island’s southern tip. Our only companions were tourist boats filled with envy.

After spending the night at anchor, we crossed the Gulf of Naples on a sunny, breezy easterly to Torre del Greco, a blue-collar town in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius. After touring exhumed Pompeii, we sailed to Naples, in search of—what else?—pizza, only to find dozens of joints claiming to be the original. Home to the US 6th Fleet, Naples has a footnote in navigation history as one of the first ports to be charted in detail using surveys from land, in 1812 by Italian cartographer Rizzi Zannoni.

I then headed north, slowing to marvel at Homer’s ability to imagine two ordinary boulders as home to sirens, women who sang sailors to their deaths. It was here, Homer wrote, that Odysseus tied himself to the mast to resist. Wally and I covered our ears.

On April 4, we arrived at the River Tiber, downstream from Rome and under the flight path to its airport. After some struggle to find a berth, I located a spot in the river itself, tied on the outside of the quay of a classy country-club marina. Its fee was 36 euros ($50) a night. I had been spending, on average, $50 a day total since leaving Tunisia, but we had now entered Italy’s more developed, and expensive, boating waters. I had $1,700 left.

Wally and I shared a taxi to the airport, where he departed and I picked up my daughter, Amy. She had little sailing experience, but by hewing close to the coastline, I felt that I was taking a reasonable risk. And, truth be told, I wanted to make up a bit of time lost with her since her mother and I divorced 30 years before. We had shared many road trips in the American West, but I’d missed so much and knew so little. She was now 38, and that night aboard, we had a good talk about her boyfriend, her job as a university fundraiser, and, for some reason lost to me now, death and disabilities. She introduced me to prosecco, and we dined on hors d’oeuvres as if we were yachties.

The next morning, as she removed sail ties while dressed in a parka, she realized that the bikini she had packed would not see the light of day. Under crisp clear skies and windshifts from east to west, we sailed to Civitavecchia behind a rugged breakwater, human-made like most marinas on the coast. The wind picked up, and it began to rain at 2 a.m. “Cold, nasty night,” my log reads.

Amy had brought an early, unlocked smartphone, and with a local SIM card, she found an Italian weather site with sea conditions. As day broke clear, we expected some onshore chop, but as we rounded the breakwater under power, we ran into the storm’s aftermath: giant onshore rollers. As Ranger hobbyhorsed dramatically, Amy, who was sitting forward, clearly scared, turned and shouted, “Daddy!” I put her into a harness, jacklined her to a U-bolt, and told her to sit near the mast, where the movement would be smaller. I raised a reefed main, but with winds less than 5 knots, it didn’t help. By midmorning, I could raise the jib and shut off the engine. It was better, marginally.

“Long, rocking day,” my log reads. “Amy was a trouper.”

At 3 p.m., she steered us into Porto Ercole, a big grin on her face. Two beers and some potato soup later, we were in bed at 7:30 p.m., “wiped.”

A terrible surge woke me at midnight. I got Amy up to move the boat parallel to the dock, bow in. At 4 a.m., I adjusted the spring line. At 9 a.m., it was rainy and windy—the Med’s many moods. I wasn’t feeling that hot either.

I’d now been a month at sea, and Amy sailed us 20 miles to a quiet anchorage. We planned two nights but knew from her phone that “stuff was coming.” We motored into a nice marina with hot showers at Grosseto. Along the way, looking west, we could see the cruise boat Costa Concordia still lying on its side three months after striking a rock off Isola del Giglio. Thirty-two people died. The captain who abandoned the ship before it was cleared was later convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 16 years in prison. It was a chilling sight, and a reminder that the Med, charted for centuries, could still snag a boat and kill.

On April 17, my third mate, Dave Pfautz, joined us, and Amy took us to dinner for my birthday. David, a nurse, had introduced me to living aboard in Key West, Florida, and had helped me find Ranger. We made a nightly ritual at sunset to sail out and watch for the green flash, and toast our good fortune. I asked him to cross the Atlantic with me, but he backed out at the last minute because of a health issue. Now he felt he could join us, and I gladly accepted his presence as payback.

Amy left early the next day, taxiing to a train to Rome. She left her phone, and a card, thanking me for all “the wonderful new memories.” I cried. Several times.

“Sea turned to shit,” my log begins for April 19. Big, westerly waves made for a rolly ride north, and an exciting entry in breaking surf into San Vincenzo. Dave threw up again, perhaps from a bad plate of clams, and I persuaded him to go to a hospital. I ate tapas alone.

At midnight, I woke to howling winds. They weren’t forecast. The waves were crashing against the breakwater at Marina Cala de’ Medici. I risked an escape, gunning the diesel out through the breaking surf. Stuff flew around the cabin. Dave was weak. It was a lumpy, tough day.

We stopped at Viareggio on a national holiday, grabbing a toehold on a crowded dock end. Set against the rolling hills and vineyards of Tuscany, with Pisa and Florence beckoning, the region might have lured me to stay if I had not been on deadline and burdened with an infirm crewman. With less than 100 miles to go, I was eager to catch the boat home.

As a result, I also passed a chance to investigate a note in Rod Heikell’s Italian Waters Pilot. Ten miles away in Marina di Carrara, known for its white marble, sat the headquarters of the two leading electronic chart companies: C-Map and Navionics.

The story of how two local boyhood friends—Foncho Bianchetti and Giuseppe Carnevali—conceived and built the first marine chart plotter, the Geonav, by digitizing paper charts and displaying them on a mobile screen, describes one of the great leaps in marine navigation. Their first unit, displayed at the Genoa boat show in 1984, cost $12,000. They made 200 that were snapped up by, among others, the King of Spain and Prince of Monaco, according to Carnevali. The friends soon split over business strategy, with Carnevali heading Navionics and Bianchetti forming C-Map. Their competition, which drove innovation, remains today in headquarters a few miles apart. Navionics is now owned by Garmin and C-Map by Brunswick Corp.

The fact that it happened in Italy, atop the long history that I had surveyed, was coincidental, both men said. And yet today, both companies acknowledge that Italian innovation, precision and artistic creativity would make it appear inevitable.

With relief, Ranger and I finally arrived in Genoa, tucked into a slip and, between sumptuous meals, began to undress for the freighter trip home. It was on this waterfront that Christopher Columbus, born in 1451, escaped his family’s sheep farm. He began to absorb the lore and avarice of merchant trading, first as a ship’s boy that took him to the eastern waters of the Med. His first documented trip was to the island of Chios, near Turkey. By this time, navigational innovation had moved to Spain and Portugal, and their explorations. Columbus followed, and the rest is history.

I said goodbye to Dave, happy to be alone with Ranger. He flew home but never recovered his once-buoyant soul. Some years later, after a motorcycle accident, he died in surgery. Whenever I see a green flash, I think of our sunset cruises and the life he introduced me to.

Ranger’s last Italian trip, a couple of miles to the Dockwise yacht-transport dock, was a nail-biter as waves ricocheted off concrete abutments, creating a maelstrom. Violently rocking, Ranger’s prop at times came out of the water. I’m not big on prayer, but as I mumbled, “Please, God,” I also shouted to the Racor fuel filter: “Don’t fail me now!”

I could understand why the Med had been seen as inhabited by spirits: evil, benign and inviting. We cruisers travel odysseys every time we shove off. It takes will and skills, vision and dreams to journey by boat.

Checking my Garmin GPS II, I saw that Ranger and I had traveled 15,000 miles. I had reached my goal—across an ocean and an ancient sea—and had gathered both a sail bag of stories and a great sense of accomplishment. I didn’t know at the time that this would be my last great sailing voyage. But at 68, I had nothing left to prove. Like Odysseus, I was going home.