“Can you come up here? It’s getting pretty shallow, and I think I’ve lost the channel.”

This inauspicious statement from the skipper, coupled with the shrill beeping of the depth sounder, had become familiar the past two days. I finished putting the coffee on to perk, and hauled myself up through Wild Rye’s companionway.

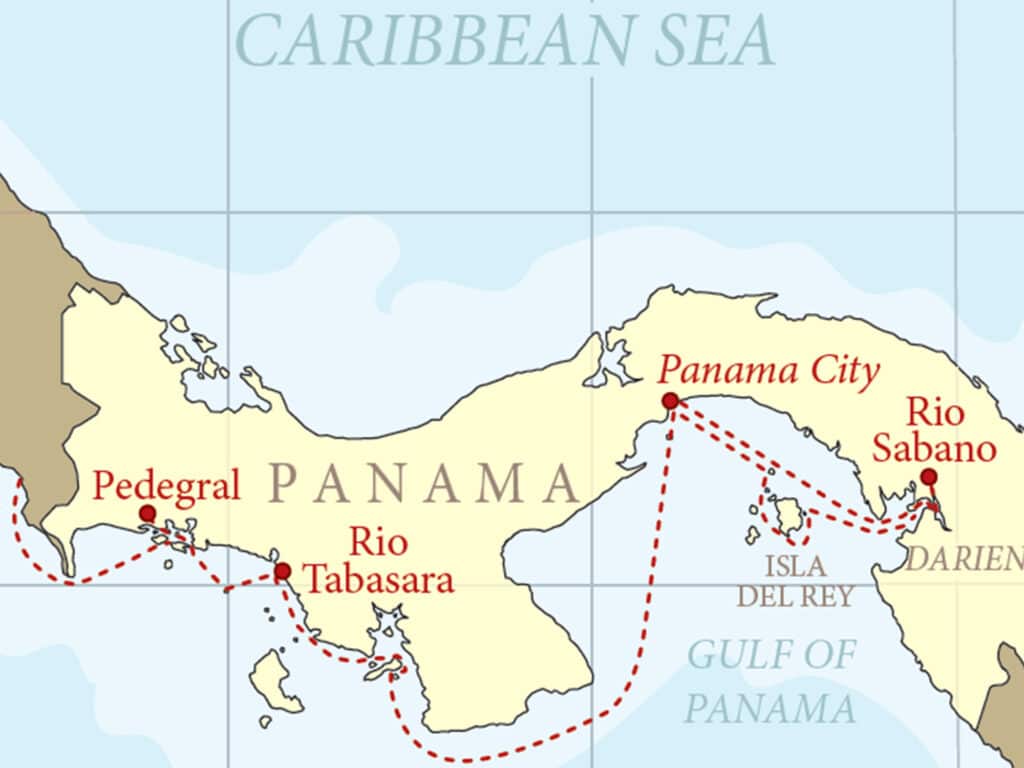

Our Wauquiez Centurion 32 was en route to Pedregal, Panama, a small fishing town some 20 miles from the sea via a winding network of estuaries. It’s the country’s westernmost port of entry on the Pacific side. Our depth sounder, circa 1980, had been working overtime ever since we’d cruised up the Estero Boca Chica Channel the morning before. We had already touched bottom twice: Once, we were able to reverse off the sandbar with the engine throttled all the way up; the second time, I got a crash course in kedging. Happily, that second time, a panga whizzed past us, saw our dilemma and did a U-turn to assist. Its skipper led us slowly back toward deeper water and around the last few bends. We sighed with relief as Pedregal came into view.

The return trip, when we could rely on our own GPS track, was much less twitchy. We had two beautiful days to appreciate the serenity of our surroundings. The wide, calm estuaries were edged with thick mangroves. A chorus of birdsong erupted at dawn and dusk. Pangas emerged from narrow tributaries and disappeared back into narrow cuts, hinting at a hidden way of life behind the dense growth.

While the Panama Canal is a crucial crossroads between the Atlantic and Pacific, our journey taught us that Panama is more than a place to pass through. It’s a place to linger.

We had departed Boca Chica’s narrow, rock-lined channel and made the sail to the Islas Secas, 15 nautical miles away. Anchored on the northeast side of Isla Cavada, our views—of deep, clear water and rugged islands—were strikingly different from the murky estuaries of the mainland coast. Crescents of pale sand fringed the deep green jungle and stark gray rocks. The afternoon haze reduced the mainland to a moody indigo smudge on the horizon. We saw no other boats, and the resort appeared to be empty.

In fact, with the exception of Panama City, we would find almost every anchorage deserted in our explorations of Panama throughout the fall season. The country had a sweet silence, only occasionally marred by our desire to share the experience with others.

Our next stop was an estuary at the mouth of the Rio Tabasara. My boyfriend, Liam, had used satellite imagery to pinpoint the location as a likely convergence of calm anchorage and surfable waves. It’s an important combination for a surf-loving guy whose girlfriend doesn’t like being seasick on the hook.

We anchored just east of the river mouth and motored upriver in the dinghy, using its anchor and rode as a lead line to find a route that would be deep enough for Wild Rye. We later dropped the bigger boat’s hook in a mangrove-lined riverbank indent. At slack tide, the water was still; with the tide running, it rippled gently on our hull. From the deck, we could see the surf break out beyond the river mouth. A few small homes dotted the edge of the estuary, with the chatter of children playing and the smell of cooking smoke. With no roads or power lines, nighttime brought silence and velvety darkness.

We spent a week in that piece of paradise. Fishermen in pangas and dugout canoes would wave. Liam found the surfing to be best at midtide. Slack tide was our cue to jump in the dinghy and head down to a rocky outcropping to jig for some dinner.

Next, we ventured east to Bahia Honda, a quiet spot where a local family has a reputation for trading with passing cruisers. Almost the moment we dropped the hook in front of Don Domingo’s property, he motored out to greet us with one of his grandsons at the helm. We bought eggs and fruit, and traded fishing lures and matches for citrus, papaya and taro root. His 10-year-old grandson gave us a picture of Wild Rye colored in painstaking detail, in exchange for a fishing lure. He returned later with two small fish for our dinner. Sitting in the calm bay, ringed by green hills on all sides and a low ceiling of stratus clouds, we felt completely removed from the outside world.

In all our travels along Panama’s Pacific coast, our interactions with local people were relaxed and genuine. Our short ventures into remote communities left an impression of a simple way of life quite far from the glossy tourist towns of Costa Rica’s Pacific coast, or the abundance of Panama City.

After we anchored at Isla Cébaco, we went ashore to explore by foot. The road was red clay and slippery-smooth from the daily rain. Water pooled in the deep ruts. A mixture of fenced pastures and lush farmland lined the road, and the air was earthy with the scent of manure and wet grass. We bumped into a farmer on a mule with a full propane tank slung across the saddle. Once he understood that we weren’t lost, he bid us goodbye with a wave. Later that week, when Liam was surfing Cébaco’s beach break, another local farmer stopped for a chat. Leaving his horse, he waved Liam over to give him advice on a better surf spot, and then proceeded to split a six-pack of beer. The only Spanish phrase Liam recognized was uno más (“one more”) every time he tried to leave.

We slowly worked our way eastward toward Panama City, which is a great place to stock up and work on the boat (it really does have everything a cruiser could need). But it wasn’t long before we craved quieter places. As soon as we could, we set sail for the Islas de las Perlas, an archipelago 30 miles south of the city, in the Gulf of Panama.

Squally conditions mellowed out as we cruised, and we enjoyed several weeks of beautiful daysailing among the islands. With numerous well-charted anchorages available and a wealth of fascinating nooks and crannies, the Perlas could easily keep a cruiser busy for months. On Islas Saboga and Contadora, we snorkeled in the clear, silky water and scrambled along sculpted slabs of sandstone at the tide line. We walked to a beach with pure, shimmering black sand, and to a tree with buttress roots that towered over our heads. The locals say it’s more than 700 years old. They call it arbol de vida, the tree of life.

We then broad-reached south to Isla Bayoneta on the falling tide, and picked our way through a narrow, rocky channel before dropping the hook in a cove tucked snugly between three small islands. One afternoon on Isla Pedro Gonzalez, where we filled our water jugs at the village tap, several hundred cormorants landed right in front of me. They descended in a smooth, dark cloud and alighted on the water for a moment before taking off again.

On Isla San Telmo, we saw the rusted hulk of the Sub Marine Explorer, one of the world’s first submarines, circa 1865. We stayed for hours to walk the beach and admire the marbled patterns of black and white sand.

After a two-week, counterclockwise circumnavigation of the archipelago, we still felt as though we had barely scratched the surface. From the Perlas, we ventured into Golfo de San Miguel, the meeting place of some of Panama’s largest rivers, and an access point to the remote province of Darien. Our first anchorage, at Punta Alegre, proved the most social. We woke to an authoritative tap on the hull at 6:30 a.m. We poked our bleary heads out of the companionway, and a cheerful man welcomed us to his town and offered us a ride to shore. After several cups of coffee and breakfast for the three of us, our guide took us on a tour, collecting various grandchildren along the way. We spent several dizzying hours fielding rapid-fire questions in Spanish. We accepted gifts of tiny shells and hermit crabs, listened to explanations about natural phenomena, and got shepherded up and down the beach by a flurry of tiny hands.

The rest of our stay in the Darien passed much more quietly. We sailed up the Rio Sabana and explored a few of its smaller tributaries, sinking into a meditation of motion and stillness that flowed with the tides. The magnificent, deep rivers offered some of the best sailing we’d ever had. With the current in our favor, not a wave in sight for miles, and a steady afternoon breeze, Wild Rye felt like it had grown wings. We skimmed smoothly at 6 or 7 knots, and experienced marvelous tranquility every night at anchor.

When we left the Darien to prepare for our departure from Panama, it was with a sense of regret for all the things we had yet to see and do. Five months, it turned out, was not enough. Beneath this region’s quiet surface is a wealth of experiences waiting to be had for cruisers with the time and patience to linger.