Galapagos

Four days out of Peru, on March 19, 2010, the “advance team” of three swallowtail gulls arrived just before sunset, wafting aloft on the high thermals, well above Ocean Watch‘s mast. The birds were like a trio of Indian scouts atop a Western mesa, taking the measure of the stagecoach snaking through the canyon. Once they had a bead on the situation, they disappeared, stealthily, to the west. They’d be back in a few hours, with reinforcements. They weren’t after homesteaders, or even sailors; they were interested in smaller, more delectable prey: flying fish.

They’d come to the right place.

Halfway between Lima and the Galápagos Islands, the crew was enjoying a relaxed day of sailing. It was a good thing, as everyone was working on little sleep. No one had wanted to miss a moment of the previous evening’s show.

Given the circumstances, and our next port of call, it seemed appropriate that the Galápagos wildlife we’d soon encounter played the central role in the work of a young naturalist named Charles Darwin, who sailed to the isles in 1835 and began to formulate his theory of natural selection—the crux of his masterpiece, The Origin of Species—based on his observations there. Hours earlier, upon the first appearance of the voracious gulls, we’d witnessed a vivid demonstration of how food chains work, of the survival of the fittest.

The gulls had disappeared at dawn; where, we wondered, had they gone? After all, we were hundreds of miles from the nearest land. But that advance party overhead at twilight gave an inkling of what the night might hold.

The encore performance began around midnight, with birds weaving high overhead. Out of the corner of one’s eye, at first, the fluttering flash of white could’ve been mistaken for a distant, falling star. But what we saw was much more immediate and animated. It wasn’t a galaxy of spearing meteors; it was a group of ravenous birds.

There was a distinct, quite civilized pattern to the subsequent banquet. The birds, several dozen strong, assembled in a wide circle, on a counterclockwise flight path. They would approach from ahead of Ocean Watch—never astern—and swoop in close aboard to starboard—never to port. There, in the waters abeam, illuminated by our green navigation light, the surface was roiled by countless flying fish.

The gulls would gracefully alight, pick up a snack, and flap off in a puff of air. The display was almost too much to process: the clear reflections of the white birds on the dark water; their clattering voices, a satisfied, throaty purr; the frothing bow wave and gentle stern wake as Ocean Watch cleaved through the seas; and, finally, the radiant sky above, the ceiling to an amazing, dynamic auditorium.

At the precise stroke of 0600, the last gowned gull flew away, and the lights at the banquet hall were raised. You could call that final bird Cinderella, for it was surely the end of the ball. But it seemed like a fitting introduction to what awaited us.

Islands in Transition

Late in the afternoon on Sunday, March 21, the southernmost island in the Galápagos chain—Isla Española—rose out of the mist just off our starboard bow. It was a stirring sight, and perhaps quite similar to what Darwin himself might have seen 175 years earlier. These days, the Galápagos Islands serve as the crossroads for international cruising sailors voyaging across the Pacific. Taken in company with its designation as a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization World Heritage site, an Ecuadoran national park, and a biological marine reserve, the authorities enforced rigorous customs and immigration procedures. So we stood off overnight to deal with officialdom first thing Monday morning.

I’d visited the Galápagos for the first time over 15 years previously and was struck by how rigorous the rules and regulations had been. At the time, I’d been in charge of a group of sailors who’d chartered two of the handful of boats available for such trips, and in two weeks of rambling about, we rarely saw another vessel. Back then, it was a rare yachtsman indeed who was granted permission to wander about the Galápagos on his or her own boat. “Pristine,” I remembered thinking. “This place is pristine.”

It still was. But as we approached the lively harbor of Academy Bay on Isla Santa Cruz, another word came to mind: busy. It was very, very busy.

Academy Bay

The very first thing we saw as we closed in on the bay was a big, three-masted “head boat” for liveaboard tourists that had come to grief on a reef just off the island’s southern coast only a week before. Though simplistic, it became difficult to dismiss the forlorn sight as a symbol of an archipelago in rapid commercial transition.

For as soon as we pulled into the bay and began searching for a place to drop our anchor, it was clear that it’d take many a shipwrecked vessel to put any sort of dent in the charter business. At least a dozen large dive boats and small cruise ships dotted the anchorage, along with several dozen private yachts of all sizes and description, including nearly 30 sailboats on a Pacific rally sponsored by a British sailing magazine.

A stroll through downtown Puerto Ayora—lined with hotels, hostels, dive shops, T-shirt emporiums, jewelry stores, restaurants, and taverns—was equally jarring. The assembled throng ranged from obviously upscale visitors on group tours to scruffy backpackers and surfers. Business appeared brisk. Darwin wouldn’t have recognized the place.

Leaps and Bounds

Over the next several days, we met many people who shed light on the ever-evolving islands, particularly Stuart Banks, an oceanographer at the Charles Darwin Research Station in Puerto Ayora, who’d lived in the islands for nearly a decade. He confirmed that the population was growing in leaps and bounds.

Local fishermen

“Fifty years ago, there was hardly anybody here,” he said. “In 1960, there were 4,000 people. Now we get between 140,000 and 160,000 tourists a year. In the last 10 years, there’s been an increase of 14 percent every year. It’s one of the greatest increases anywhere, and that kind of pushes everything else.”

Obviously, according to Banks, the influx of vacationers, particularly eco-tourists, was growing exponentially. But international visitors were only part of the influx. More Ecuadorans were arriving to benefit from the increasing opportunities.

Unofficially, we were told that there were upward of almost 50,000 full-time residents at the time of our visit, spread over five of the group’s 19 islands—the rest are uninhabited—with the grand majority centered on Santa Cruz. The trend was clear.

A lot of what Banks and his fellow researchers at the Darwin center address in their daily occupation is “the inevitability of climate change” and how it relates to the incredible biodiversity that literally defines the place and has for centuries.

“In the Galápagos Islands, we still have the opportunity to do something, but that window of opportunity is rapidly closing because Galápagos, like most other parts of the world, is also developing very rapidly,” said Banks. “Galápagos was once disconnected from other parts of the world because logistically, the islands were particularly inhospitable places to be. Now all that’s changing, and Galápagos has connectivity to the rest of the world that was never there before.

“There are all these additional human effects,” he continued. “Fishing, tourism, perhaps local pollution in port zones, local development, and how all that intersects with this complicated climate dynamic, which is particularly difficult. In other parts of the world, people are trying to do the same, but there are few places like Galápagos, where in many senses it’s a natural laboratory to follow processes and see what’s really going on.”

Thanks to Banks and his colleagues, the isles remain a living marine lab, and in that sense they’re also a microcosm for the grander world in which they’re a small but important part. As in the rest of the planet, more than even climate change or global warming, the greatest threat to the islands, and to mankind, seemed elemental: too many people.

At least that was our supposition strolling down the bustling streets of Puerto Ayora, a tiny dot on a twirling planet that might just be spinning out of control.

Lonesome George

Nearly everyone who visits the Galápagos makes a pilgrimage to the Charles Darwin Research Station to pay a visit to the gargantuan tortoises. After all, it’s how the place got its name: the translation of galápagos is “giant turtles.” The most famous, and stubborn, of these animals is known as Lonesome George, and he is perhaps the most confirmed bachelor ever. Now nearing his 100th birthday, George has yet to find a mate. Still, when one gazed into his eyes, he seemed like a wise, contented soul. And when you investigate the history of Galápagos tortoises, it’s clear that he’s lucky to be around.

Giant turtles

On our ongoing travels, we’d been struck time after time—in the Bering Sea, in the high Arctic, in the Canadian Maritimes—by the havoc once wreaked by the worldwide whaling trade of the 1700s and 1800s. In the Galápagos Islands, the whalers struck again. The big, rich saddleback and dome-backed turtles that once roamed the islands by the tens of thousands were prized specimens to the crews of the whale ships. Easily taken, laden with delicious, sweet meat, and with a long shelf life, requiring neither food nor water, the giant turtles—which can weigh up to 500 pounds and live for over a century—provided fine provisions for the far-ranging whalers.

In fact, the Galápagos Islands were a doubly enticing destination: Sperm whales were in abundance, and crews could stack their holds with literally hundreds of turtles for the long voyages ahead. A cargo of 300 turtles or more wasn’t unusual. In 1846 alone, there were 735 ships in the Pacific fleet. Aboard every one of them, there were dozens of hungry sailors who loved their turtle. They almost loved them to extinction.

Ironically, the same creatures responsible for the devastation of the tortoises—human beings—ultimately came to their rescue, first in the pursuit of scientific research, and later in the name of conservation and preservation. In 1964, the Charles Darwin Research Station was established, and in the years since, thousands of giant tortoises have been bred and/or raised at the center’s captive breeding center and returned to their natural habitat. The turtles again frolicked.

Handholds and Hammerheads

The iguanas, blue-footed boobies, penguins, seals, and frigate birds are what most visitors long to see in the wild during their time in the Galápagos. To do so, one must still enlist the services of a licensed guide. While several of the crew booked sanctioned trips to other islands for hikes and terrestrial tours, photographer David Thoreson and I chose to see what was happening below sea level.

Swallowtail gull

The Galápagos have become one of the planet’s premier diving destinations because without fail, once you’re in the water, you’re guaranteed the opportunity to interact with big animals: surprisingly graceful sea turtles, playful sea lions, and majestic rays, including mantas, that fly beneath the seas. Then there are fish: grunts and wrasses and snappers and idols and grouper and barracuda and parrotfish and on and on, of every size, color, and description.

Finally, there are sharks: white- and black-tipped reef sharks. Galápagos sharks. Hammerheads. On our first day of diving—initially to a location called Isla Beagle, on the southern flank of Isla Santiago, which is also known as Isla San Salvador, and then to a low, sandy island called Isla Mosquera, just north of Isla Baltra—we saw them all.

We also saw plenty of coral, in a variety of species, including prominent coral heads, intricate expanses of coral reefs, undulating sea fans, and big, oval sculptures of brain coral. Almost always, reef fish or sharks swam nearby, in various stages or acts of feeding or cleaning. It was a vivid, industrious, colorful, and vital panorama.

From oceanographer Banks, we’d learned that the coral we viewed was susceptible to changing climates and to El Niño events.

“When we get a strong El Niño, it can drastically change the entire marine ecosystem,” he said. “We’ve seen that already. We know that Galápagos corals are some of the most sensitive groups to climate change, and in the very intense 1982-1983 El Niño, the Galápagos lost about 97 percent of its reef-forming corals in a year and a half. They were bleached through hot-water stress, in which algae that forms in the corals is naturally expelled. It can always reintegrate back into the skeleton if conditions change, and the coral can recover. But when that stress is sustained for long periods, it’s not possible. Then the coral starts to die.”

The broader problem, of course, is that coral reefs are building blocks, even frameworks, for entire undersea communities. Banks said, “A whole host of other species—sea urchins, sea cucumbers, sea stars, reef fish—are all interactive and interdependent on this coral resource. So within about a year, the entire character of the ecosystem in Galápagos changed, because these are habitat-forming species, species that are particularly important in nursery areas. They give shelter and protection, but they also give kind of a three-dimensional complexity and structure in which other species can co-exist.”

Acts of nature were only one part of the potential problem. People, naturally, were the other. Overfishing can also topple the delicate balance in reef life. When lobsters and other reef fish were taken off the reef in abundance, the sea-urchin population skyrocketed. “The sea-urchin explosion infiltrated the reef structure and started breaking apart these reefs from the inside,” said Banks.

A second El Niño in the late 1990s caused more destruction to the reefs. “Today, coral reefs are fragmented across the entire archipelago,” said Banks. “What we think has happened in the 10 years since the last strong El Niño event is that the natural capacity or resilience of the system to recover has been compromised. And only now is it starting to show some promising signs of recovery.”

We understood what Banks meant; the fragile state of coral reefs underscored the very point we’d been trying to make on the expedition. Everything, and everyone, was a piece of an important puzzle, dependent on one another—a cog in a wheel that doesn’t stop turning.

“A large part of what we do is make sure we can represent what’s happening below the waves,” he said.

On our final dive in the Galápagos, on a site called Gordon Rocks, where the current sweeps through a narrow pass at up to seven knots, Thoreson and I underwent an experience “below the waves” unlike anything we’d ever seen or done before.

Following dive-master Jimmy Pincay, we slipped off the dive boat and into a maelstrom. Descending along a sheer, vertical rock face blasted by what felt like 50-knot gusts, we picked our handholds carefully, knowing that if we slipped, the current would suck us into the void. It was like mountain climbing, but exactly the opposite. We weren’t scrambling toward a summit, but into the deep.

As we pulled ourselves down, hand over hand, our finned feet were forced out directly behind us, fully horizontal, like cartoon characters in a cartoon hurricane. In what seemed like an hour but was probably 10 minutes, we negotiated the first section of rock and wedged ourselves into a series of outcroppings. From there, we had a good view of what was happening in the pass. It was something to behold.

Schools of undulating reef fish, as if a single organism, churned and pulsed past, followed by a flapping sea turtle that seemed to teeter on the razor’s edge of control. A reef shark swam purposely past, followed by another. Then Pincay was again on the move.

It’s hard to describe the sights and the sounds, the big sucking of air, the wafting bubbles of water. Every so often, a different surge of current swept past, almost pulling the masks off our faces. It was terrifying.

And then, after a few minutes of it, after getting somewhat comfortable and realizing we were all on top of it: Man, it was cool.

In the final moments of the dive, before Pincay signaled for us to begin surfacing and we made one last safety stop, we found another spot to bivouac and watched the undersea world flow by. Neither Thoreson nor I ever knew how imposing a hammerhead shark could look until we saw one, up close and personal, and some 90 feet down.

The Around the Americas expedition was conceived as a journey to spotlight the health of our oceans. Sometimes, ironically, we’d been so caught up in the concept, the science, and the mission that we’d forgotten about the sheer power and glory of Mother Ocean. But wedged in those rocks, raked by those currents, surrounded by abundance—of color, of nature, of life—in a moment that was both serious and serene, we remembered the reason we’d come here in the first place.

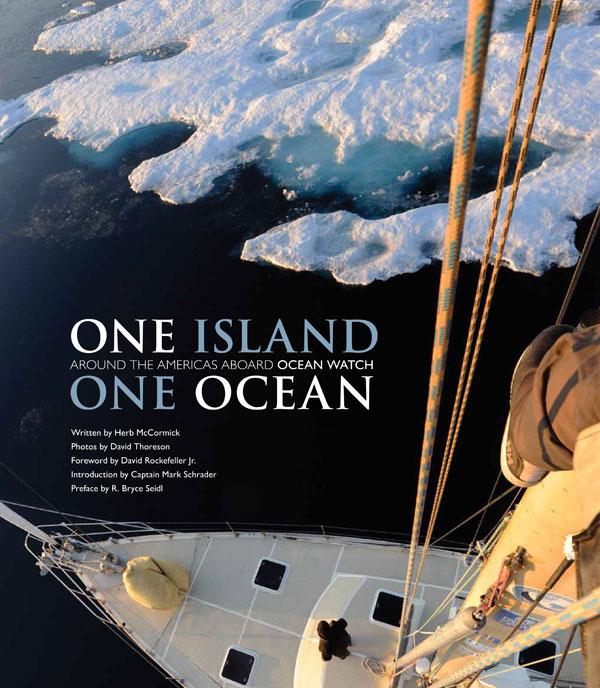

Herb McCormick, CW’s senior editor, and photographer David Thoreson were two of the four full-time crew on the 2009-2010 Around the Americas expedition aboard the 64- foot cutter Ocean Watch.

This story is excerpted from One Island, One Ocean (Weldon Owen, $35). The full-color book, written by Herb McCormick and with photos by David Thoreson, recounts the historic 2009-2010 Around the Americas expedition. It’s now available online at outlets including Amazon.com