If there was one thing we’d learned in our first couple of weeks in Costa Rica, it was that the country is absolutely brimming with life. All kinds of life, in all kinds of places.

Our water tanks, for example, were being colonized by disconcerting white algae that had taken hold in the tropical climate. Black-and-white mold speckled the bottoms of cushions, the edges of books, and the damp corners into which breezes rarely ventured. On one memorable evening, as the last of the day’s sun diffused across the hazy horizon following an incredibly torrential downpour, a fledge of termites descended and covered the just-rinsed decks in a disgusting layer of insect paraphernalia. They dropped into the boat through the open hatches until we gave up and closed everything. We found them crawling up our legs, clustered in the corners of the settee cushions, and absolutely coating the cockpit, plastered down by rain. For days afterward, we found termite wings littering the boat, like stray confetti after a party.

We first arrived in Costa Rica in June following a monthlong passage south from Mexico’s Sea of Cortez. Wild Rye, our 32-foot 1971 Wauquiez Centurion, was coated in a stubborn layer of salt and dust, remnants of northern Mexico’s desert-type climate. My partner, Liam, and I were feeling equally grubby after the passage, our faces sunburned and clothes stiff from sea spray. The cool rains that greeted us in Costa Rica were divine. Having arrived at the start of the rainy season, we had no doubt that there would be more where that came from. For the next several months, our small world would be shaped as much by fresh water from the skies as by the salty ocean that held up our floating home.

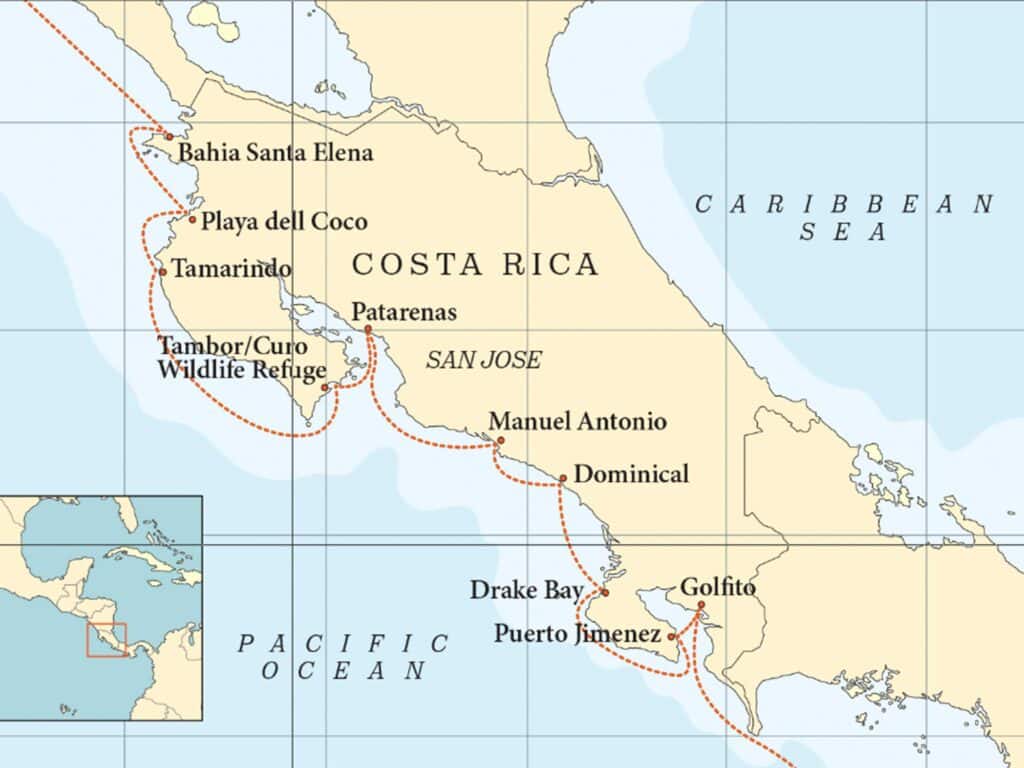

We started our explorations in Bahía Santa Elena. A bay within a bay on the remote northern edge of Santa Rosa National Park, protected from the southwest swell by its orientation and from the gusty Papagayo winds by the high hills to the north, it was a haven of stillness after a long month of constant motion. The only noise was the rush of wind over the hilltops high above and the constant background chatter of the jungle. Howler monkeys roared, tropical birds called, and, at dawn and dusk, enormous flocks of parrots filled the air with their strange, rambunctious conversation.

Paddling up the estuary in the dinghy on the rising tide was like entering another world. Light filtered through the mangroves, and the harsh midday sun softened to a dappled glow. Blue morpho butterflies winked in the trees like bright jewels, and colorful land crabs scuttled along mangrove roots suspended over the water. We spent hours drifting and listening to the unfamiliar birdsong, our ears transporting us even when our eyes couldn’t pick out the wildlife tucked away in the dense greenery.

Another day, we hiked up to a ridge overlooking the bay. Our guidebook had an old map of hiking trails in the national park, but when we finally found the start of one, it clearly hadn’t been used for some time. The dirt road had been obscured by fallen trees and heavy curtains of climbing vines. Liam seemed to intuit, rather than actually see, the path under our feet; I crossed my fingers and followed.

After an hour of serious bushwhacking, stopping every so often to pick small spines and burrs out of our clothes, we came around a corner and encountered a trail crew. The sight of two men with machetes and an Isuzu Trooper towing an ancient grader was decidedly surreal. We stretched our legs with pleasure on the crisp, newly cut swath, kicking up clouds of dusty red earth and admiring the strange mix of cactuses and deciduous canopy cover that characterizes the tropical dry forest in northern Costa Rica. On the return trip, we passed the trail crew again; they had made it about 300 feet farther into the dense growth before the grader overheated. Based on how many times my ankles had been snarled by strong, spiny vines, I was not surprised. The tireless growth of the tropical forests strikes me as a life force that far outmatches any human efforts to tame it.

For a tiny country, Costa Rica packs a mighty punch when it comes to ecological diversity. Although it makes up less than one-tenth of a percent of the Earth’s surface, it is home to nearly 6 percent of global biodiversity. Due in part to its geographical position—sandwiched between North and South America, as well as the Pacific and Atlantic oceans—and in part to its mountainous topography, the country contains a wealth of ecosystems and microclimates, from chilly, high-altitude cloud forests to coastal mangroves and everything in between. With more than 25 percent of its landmass protected in the form of national parks, reserves and refuges, Costa Rica has become something of a symbol of biodiversity.

As we meandered south, we visited as many of these protected areas as we could, enjoying the gradual transition from the tropical dry forest to muggy, muddy rainforest. For two Canadian gringos who have spent the majority of our short lives north of the 49th parallel, this land of eternal summer with creatures such as the tapir and tamandua, the kinkajou and bushy-tailed olingo, hummed with opportunity for new sights and experiences.

In the Curú Wildlife Refuge, on the southern edge of the Nicoya Peninsula, we stepped softly through groves of fruit trees and coconut palms left over from the area’s agricultural history. Feisty capuchin monkeys threw down half-eaten mangoes to defend their territory, and the air was heady with the scent of fermenting fruit. In the dim purple twilight, a coati sashayed past, tail held high, nose scuffling the forest floor.

Farther down the coast, we anchored in front of Manuel Antonio National Park—the country’s tiniest and one of its most visited parks—and spent a day watching the local sloths as they blissfully alternated between snoozing and munching on leaves in the forked branches of cecropia trees. More than any other animal we were lucky enough to see, the sloths seemed to embody the mellow pura vida lifestyle for which Costa Rica is known.

With their goofy, blissed-out grins, I imagined them to be saying, “Take it easy, man, life is good.” And it sure is.

On the Osa Peninsula, Corcovado National Park grows increasingly popular for its lush biodiversity; it’s one of the most biologically intense places on Earth. Instead of paying the steep park fees, we explored the fringes of the peninsula’s intensely humid rainforest. We anchored in Drake Bay to make use of the public hiking trail that runs for 10 miles along the coast, all the way to the San Pedrillo ranger station on the edge of Corcovado.

We saw brilliant blue-and-yellow gartered trogons, and a family of capuchin monkeys, one mother still with a tiny infant clinging to her back. We hid from the daily deluge of rain under the broad, leafy canopy of a gnarled old tree, having foolishly declined a friendly fisherman’s offer to join him under the tarp shelter of his panga. We plunged through ankle-deep mud in our rain boots. Although we had anchored in Drake Bay with jungle exploration in mind, I instantly fell in love with the anchorage for its beach, as well: a wide, sandy crescent bisected by several creeks running down to the sea, with a high green hill at its back into which the town disappeared. The ocean, at its front, was as calm as a millpond.

The rich, life-filled wildness of the Costa Rican jungle is not limited to parks. Everywhere we went, we were struck by the denseness of the trees, which grew unchecked right down to the tide line. Even the largest coastal towns were half-hidden within a leafy embrace and hard to spot from the water, buildings further camouflaged by their tin roofs, which oxidized to a pale, mottled green. Every beach we visited was lined with verdant growth, trees wreathed in mist in the early mornings, and pools of shade in the heat of the midday sun. From their thick canopies came the strident song of kiskadees and the high, fluting calls of toucans. From overhead, I imagine the country looks like a sea of green, with canopies ruffled by the wind like waves on water. An ocean of trees.

Next to the lush forests—but in a way intimately connected to them, because it is the rain, in part, that fuels that verdant growth—what I will remember most about Costa Rica is water. At the end of our first week, we were running desperately low, a result of having placed too much faith in other cruisers’ assurances that it rained all the time. With only 2 gallons left in our last tank, we anchored in front of the small fishing town of Junquillal, just east of Bahía Santa Elena, and dinghied in to ask around.

Feeling a bit shy after weeks of solitude, we approached the fishing dock and waved at a group of surly-looking fishermen playing cards in the shade. In response to our slow, heavily accented Spanish request, a fisherman walked over, grinned and said: “I like your little boat. And sure.” He shouted something in rapid-fire Spanish, and another guy walked over, dragging the end of a well-used and abused hose. The two men stood chatting with me (I used the word liberally; I probably caught about one word in five) while I filled our jerry jugs, and then they helped me lug them all back to the dinghy. As we cast off, dinghy loaded to the gunwales, the group wished us well with shouts of “Pura vida!”

We never ran low on water after that. Docks at every fishing pier and coastal resort, no matter how decrepit or luxurious, all seemed to have a water hose, and everyone was happy to share. As we headed south and the rainy season established itself, we reveled in the torrential afternoon rains that could fill our tanks in an hour. There was the cool relief of cloud cover as towering thunderheads built, fueled by the heat rising off the land; the crisp freshness of rain, washing away the salt of sweat and sea spray, delightfully and tinglingly cold on our skin; the relief as rain drove away the afternoon heat, and the equal relief as the next morning’s sun chased away the lingering dampness. Everything we had read and heard about Costa Rica during the rainy season indicated that it would be too wet and uncomfortable. The reality was that we absolutely loved it.

Looking back, what we appreciated above all was the sense of transition, through ecosystems as well as seasons.

Looking back on our three months in Costa Rica, what we appreciated above all was the sense of transition, through ecosystems as well as seasons. As we floated south, we moved toward the rain in space and time: from drier to wetter forests, lower to higher average rainfall, and toward the wettest months of the year, which are August through October. It was a continuation of the transition we experienced when leaving Mexico’s arid heat and venturing into the humid tropics, which is itself the mirror image of the transition we experienced when we made that first big leap from Canada. As people whose home is forever on the move, it might seem like we’ve abandoned the seasonality of Canada for eternal summer, but we are moving through seasons, all the same. It’s just that the motion is geographical more than temporal.

Now, as the rainy season approaches its zenith, we start to look ahead to the next change, the next place. Perhaps from here, Wild Rye will find her way out of the tropics and back into the higher latitudes. After a few magical years of endless summer, we think it might be nice to see some snow again. And so, the cycle will continue, until one day our season of travel comes to its natural end, and the next change, the next adventure, will be found back home where we started.

Hilary Thomson and her partner, Liam Johnston, have been living and traveling aboard their 1971 Wauquiez Centurion 32, Wild Rye, since 2019. Their eastern Pacific journey encompassed points northward to Haida Gwaii, in northern British Columbia, and southward to Panama City.

Weather and Sailing Conditions

Costa Rica’s Pacific coast has two distinct seasons: dry, from December to May; and rainy, from June to November. The driest weather is in Guanacaste province in the north, and the rainiest part of the country is the Osa Peninsula.

During the dry season, there will be more-consistent wind for cruising, but the country is affected by the Papagayo gap winds: strong, intermittent northeasterly winds that commonly blow 30 or 40 knots, with gusts up to double the forecast windspeed. They are strongest from December through March, when the northeast trade winds are at their height in the Caribbean. To sail through the Papagayos, follow the shoreline carefully to avoid the fetch that builds farther out to sea.

During the rainy season, winds tend to be light. Take advantage of the regular afternoon onshore breeze if you want to cover any miles under sail. Rain squalls bring short-lived periods of stronger wind, often accompanied by lightning and heavy rain that can obscure visibility. The storms are most common in the late afternoon and early evening.

Costa Rica sits on the southern edge of the Northern Hemisphere hurricane zone, which affects Pacific Central America and Mexico as well as the Caribbean. However, Costa Rica is far enough south that the risk of a hurricane landfall is low.

Anchorages

Many anchorages on the Pacific coast are fairly exposed to southwest swell; be prepared for a lot of rolling, especially from May to October, when the southwest swell is at its largest. Setting a stern hook to hold the bow into the swell will help keep the boat comfortable. Exposure to swell also makes for sporty (or occasionally outright dangerous) dinghy landings. Expect to navigate many surf breaks, and watch the local pangas for an indication of the best approach. To escape the swell, consider exploring the Gulf of Nicoya and Golfo Dulce, which are sheltered by Costa Rica’s two large peninsulas and have many interesting anchorages.

In the dry season when the northeast trades and Papagayos are blowing, swell will be less of an issue, but protection from northerly winds and fetch will be important.

The Pacific coast of Costa Rica has significant tides (generally around 8 feet), so plan your shore arrivals accordingly, and make sure to tie your dinghy well.

Formalities

Upon entering Costa Rica, cruisers are given a 90-day cruising permit. Extensions are no longer permitted at the expiration of the cruising permit, and it is not possible to reenter Costa Rica for three months. When we were in Costa Rica in 2021, all cruisers were required to use an agent to check in because of the pandemic. For us, the use of an agent made an otherwise-lengthy process easy. I was quoted prices between $375 and $450 for the check-in service, with a significant discount (around $100 off) for members of the Panama Posse, a go-at-your-own-pace cruising rally between Southern California and Annapolis, Maryland, via the Panama Canal.

Ports of entry in Costa Rica include Marina Papagayo, Playa del Coco, Puntarenas, Caldera, Quepos and Golfito. Marina Papagayo is the northernmost port of entry; customs and immigration officials are located in Liberia, and the port captain is in Playa del Coco, each about 25 miles away, so hiring an agent might be cost-effective compared with the taxi fares and time required to do it yourself. Golfito, the southernmost port of entry, has several marinas with immigration, customs and the port captain located nearby, so clearing in or out here on your own is straightforward. Our exit clearance, which we were able to complete ourselves, cost about $15. Many officials in Costa Rica speak English, but don’t count on it. All marinas will have helpful English-speaking staff.

Cost

We found daily items such as groceries, beer and fuel to be cheaper than or on par with American prices, while tourist-oriented items such as marinas and dining out were often more expensive. Marinas ran from $2.50 to $3.50 per foot per night; beers were about $1 each. Dining out was variable; the cheapest meals were reliably found at soda restaurants (much like American diners). Free potable water is available nationwide, and hoses can be found at most docks.

Guidebooks and charts

We used Sarana’s Guide to Cruising Pacific Costa Rica and Panama(2015) by Eric Baicy and Sherrell Watson. It’s an affordable e-book with useful sets of waypoints for approaching anchorages and navigating tricky areas. Also available is Charlie’s Charts: Costa Rica by Margo Wood. We found Navionics to be fairly accurate throughout the country; however, many hazards are uncharted, and we would not recommend traveling this coast without a detailed guidebook. —HT