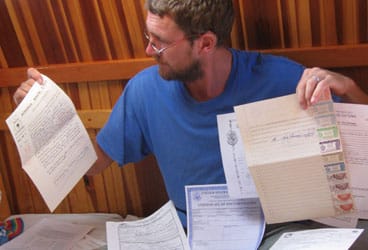

Sailing Papers

The secretary handed back all my documents in a tidy heap. “All I need to see now is your boat-import permit,” he said. I tried in vain to stuff the mass of papers into an envelope that was far too small. “My, umm, what?” I asked vaguely.

“The import permit,” he said. “You should have gotten it when you entered the country.”

“All I have is what I gave you.” I looked up blankly. “No one ever mentioned an import permit.” I was procuring a slip at the marina in Huatulco, our next-to-last stop in Mexico, and Eduardo had already photocopied every official paper I’d accrued in five months of cruising along that coast.

“Really?” He seemed incredulous. “None of the port captains you visited asked to see it?”

“Well,” I admitted ruefully, “we’ve only been to see two since we checked in at Cabo San Lucas.”

It wasn’t that we were trying to dodge them, but we’d been told at the La Paz office that once checked into the country, it wasn’t necessary to see the captain in every port. All they required was a hail on the radio upon entrance and exit. This, of course, was contrary to what the port captain in Cabo San Lucas had told me as he gave me a zarpe—an official departure certificate—for Santa Rosalía, another Mexican port well inside the Golfo de California.

We hadn’t made it that far before turning to sail back south toward La Paz, so that zarpe benefited no one except the government, which charged US$20 on my credit card for it. I’d been nervous about arriving in La Paz with a zarpe for Santa Rosalía that was several months old and none of the crew on the official crew list still on board, but when they didn’t even look at the registration, my fears were somewhat allayed. Still, it was one of the first questions we asked other cruisers in every new port, after the usual pleasantries about the roughness of the passage and the poorness of the holding had been discussed: Did you go see the port captain? Does he care if you see him?

The answer varied from cruiser to cruiser. Some conscientiously made an effort in every port; others never bothered, figuring they’d sort everything out, even their expired visas, at the far end. The guidebook, of course, stresses the importance of checking in and out at each place that harbors a port captain. But often it just seemed like a fool’s errand. And it wasn’t just the port captains. Aside from the newly formed park service, from which a permit could be purchased to anchor at various barren islands in the Golfo de California, there was an entity known as the AdministraciÓn Portuaria Integral that supposedly held jurisdiction over certain ports and their facilities. It was said that the A.P.I. people levied a nominal daily fee, and some people dutifully went in to pay it. Others, we learned, blithely disregarded it with no discernible repercussions for their delinquency.

It isn’t that anyone wants to break the rules; it’s just that no one seems to know what the rules are. It doesn’t help that everything has changed almost yearly since I first cruised in Mexican waters in 1995. Even the basic sequence for entering the country, while always involving some combination of port captain and immigration, changed in the order of who had to be seen first and whether a trip to customs or to the bank to pay a bill was necessary. One time it was mandatory to have a zarpe to move from one port to the next; lately it seems the port authorities don’t want to be bothered, since there’s no cash fee to collect. Sometimes you’d hear of boats fined for not having fishing licenses for all aboard. Others scoffed at that, citing numerous navy inspections with never a mention of such things.

So it was hardly a surprise to find that we’d been cruising semi-illegally for five months without even knowing it. By that time, I’d decided our duty was to do whatever was important to the official in whose hands we were in just then, and if the mysterious A.P.I. or any other agency wanted some money, its reps could jolly well come out and ask for it.

“Is it something you really need?” I asked Eduardo, wondering why a marina operator cared about the import status of a passing sailboat, just as I wondered how many times my long-expired proof of insurance would continue to fly. (“That was my insurance in the U.S.,” I told the lady at the marina in La Cruz. “It never had coverage for Mexico.” She never turned a hair. “That’s all right,” she said. “I just need a copy of an insurance document.” Any insurance document, it seems.)

“Oh, I don’t need it,” Eduardo said. “But the port captain will ask for it.”

“All right.” I rolled my eyes at his turned back and neglected to mention that I had no intention of visiting the port captain. Why rattle the gorilla’s cage? I’m not normally a scofflaw, but we’d wasted too many hot hours, not to mention pesos, in different cities dutifully chasing down one official or another for a permit that they no longer issued. Only once, in Puerto Ángel, had the captain wanted to check us in or out, and he’d sent his secretary down to the beach to stake out our dinghy landing and hail us to his office. I thought we might be in trouble, since we’d been there for four days already and he’d sent word twice via some other sailors that we ought to check in. But he merely photocopied our passports, gave us an updated crew list, and sent us along to Huatulco.

Eduardo returned the last of the documents he’d copied and sat down to fill out an elaborate form. “Bring it in when you’ve got it, and I’ll put a copy in the file.”

“Umm, sure.” The file was already of a staggering size. I wondered about who’d ever read it.

It took half a dozen signatures and initialing to satisfy Eduardo’s requirements. It seemed more like a rental agreement for an apartment than for a fortnight’s side tie to a floating pier with no power or water.

When we left for Puerto Chiapas, the last Mexican port before Guatemala, Eduardo’s file still didn’t have a copy of any import permit. A week later, sitting in the coolness of the Puerto Chiapas port captain’s office to apply for exit papers, I worried about it, but only for a moment. It soon became evident that though doing things according to his orderly fashion was very important to this port captain, whatever anyone had done before wasn’t a concern of his. And so we sailed out of Mexico a few days later with a handsome handmade zarpe certificate, though for the last five months the boat had been practically unpapered, uninsured, anchoring in arrears, fishing illegally, and flagrantly trespassing—or not, depending on whom you asked.

Ben Zartman, who spent four years chronicling the building of Ganymede_ as_ CW_’s Backyard Warrior, is now enjoying the fruits of that labor with his wife, Danielle, and the girls. Having explored the Golfo de California, the Zartmans have set their sights on Panama’s San Blas islands._