DavisMurray368

Pink. The audience is a resounding shade of pink, their collective tint suggestive of far too much tropical sun and several rounds of lunchtime drinks. “Damn,” says a fellow in one of the more ridiculous floral shirts ever created, a melange of colors that simply do not exist anywhere in the natural world. “We look like tourists.”

“That’s because,” his pal says, a bit too glumly for a party animal on a rippin’ trip to the islands, “we are.”

It’s 3:30 in the afternoon in an open-air courtyard at the exceptionally well-named Point of Sale Mall hard by the gleaming, downtown cruise-ship docks of St. Thomas, in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The assembled crowd, having spilled ashore from one of the bulbous white cruise ships nearby, represents the Atlanta chapter of what has become an international string of Parrothead Clubs, whose members worship at the altar of all things Jimmy Buffett. They’re on their yearly swing through the islands (during which, it should be noted, they raise money for charity), and they’re more than ready to be entertained by an authentic island character.

They’re not kept waiting.

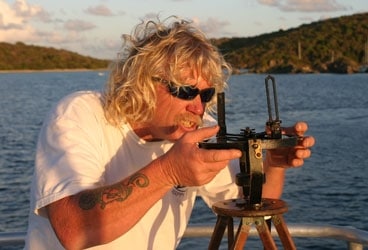

For suddenly, there before them stands a rather strapping dude in dark shades and baggy Hawai’ian shirt, his Harley-Davidson mug haloed by an unruly blonde helmet, wearing a pair of khakis that look like they were last washed and ironed during the Clinton administration.

“I’m Barefoot Davis,” the shoeless one says, strapping on his black, carbon-fiber guitar and nodding at the musicians who’ve assembled behind him, “and this is the Barefoot Davis Band. Welcome to St. Thomas. It takes an hour and a half to watch 60 Minutes down here. Don’t forget that.” Then he launches into a song, the refrain of which poses a curious existential question: “How many lies are in that whiskey bottle?”

Truth be told, I met Davis Murray-the handle he was given when launched into life a little over five decades ago in Brookfield, Massachusetts-a long time ago. A jack-of-all-nautical-trades, his reputation as a top-notch compass adjustor, navigator, boatbuilder, mechanic, offshore sailor, beach-cat racer, and all-around raiser of hell is firmly established up and down the Eastern Seaboard and throughout the Caribbean. And anyone who’s ever done the annual Caribbean 1500 cruising rally knows him well. He’s sailed all 18 rallies to date and serves as the event’s fleet captain, troubleshooter, and general guiding light at its outset on Chesapeake Bay, under way via the daily radio schedule, and at its conclusion in the Virgin Islands, which he’s called home for more than a decade.

Still, when I’d heard that Murray had picked up the guitar, formed a band, landed a record contract, and produced a CD, I was somewhat, shall we say, astonished. So when I found myself with some free time in the Caribbean last spring and he invited me to come hang out for a few days, I quickly accepted his offer. Which is how I found myself swaying to his beat with a bunch of Parrotheads on a lazy weekday afternoon.

For as it turns out, Barefoot Davis has written some pretty catchy tunes that he and his band-all of whom, he readily admits, are far more accomplished musicians than he is-execute with more than a little skill and flair. When the afternoon gig ends, to solid applause, I clink beers with him and admit that I’m quite pleasantly surprised.

“Yeah, well, someone came up and asked me to do some Buffett tunes,” he says, sharply, sounding precisely like the Davis I’ve always known. “I figured they get enough of that on the ship. Hey, I like Buffett, but we’re not a cover band. This is my island, and this is our sound. If they don’t like it, they can split.”

He pauses for an instant, the punch line briefly hanging in the air, and smiles broadly. “But you didn’t see too many leave, did you?”

Hectic. When one spends several consecutive days in the company of Davis Murray-particularly when his wife, Margot, an accomplished sailor herself, takes off for a cruise of the Grenadines with some friends-the pace of life is hectic. It’s most definitely not an exercise for the energy impaired.

Luckily, when we hop into his RIB the next morning and set forth from Splinter Beach, the 34-foot lobsterman-style motor launch the Murrays call home, the first stop is for caffeine at a place around the corner from his slip on the east end of St. Thomas: Lattes in Paradise.

“Davis!” cries a choir of enthusiastic coffee drinkers, in unison, as he enters the shop, where his first CD, Daydreamin’, is prominently on sale.

“You know who you remind me of, Davis?” wonders a jarringly attractive woman as we await our orders. “Norm, from Cheers. Nobody else gets a greeting like that.”

“He’s the mayor of St. Thomas,” says Danny Silber, the classically trained keyboardist and jazzman and a prominent member of the Barefoot Davis Band, back at the Sapphire Beach Marina. Silber lives there in a one-bedroom condo-the centerpiece of which is the giant grand piano plunked down right in the middle of it-just a stone’s throw away from Splinter Beach’s dock. Murray has decided we should take a leisurely putter through the Virgins, and while he’s readying the boat, I chat with Silber about the band and their music.

“Davis just has a knack for writing clever song material,” says Silber, who left New York City for the islands years ago and never looked back. “Once he surrounded himself with quality musicians, he just blossomed. It’s simple music, three or four chords. But there’s an art to playing simple takes well. There’s no place to hide. Miles Davis said that.

“He doesn’t have a smooth voice, but neither does Bob Dylan. But he’s totally in the moment. It gives the band great spontaneity. With Davis, you never know when the magic will come. That’s the great thing about magic, about live music. I mean, you can’t say, ‘All right, let’s put the magic in at 9:10.’

“And the other thing about Davis-he’s a great self-promoter,” concludes Silber. “Shameless. Is there any other kind of self-promotion? It’s a show, and that’s why they call it show business. But this is one of the most fun bands I’ve ever been a part of.”

Moments later, we’re off in Murray’s old beater on the day’s errands, which are put on hold every time we’re greeted by a grand, oceanic vista, at which point he immediately spins off the road to deeply drink it in. “You always have to keep in perspective what brought you down here in the first place,” he says. “I know a lot of people who forget about that and don’t take advantage of what we have here.

“I, fortunately, do.”

The day is a whirlwind. We stop off at ISW, Murray’s recording studio, while he lays down a guitar track over his pirate tune, “Dead Man’s Grave,” for an upcoming Pirates of the Caribbean compilation CD. “I like what’s happening, Davis,” says his producer, Dan McGuinness.

The pirate theme continues as we check in on Carteza, a converted Cheoy Lee Offshore 41 that Murray helped completely overhaul into a faux pirate ship/playground for the children of a wealthy Midwesterner who has a mansion on the island; Murray now oversees the boat. He fiddles with the cannons and takes a swing in the hammock, just another one of the kids.

Next, we’re back on the water, where Murray pockets some change swinging the compass on a fast, twin-hulled interisland ferry, the trade he plied from the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s on the Philadelphia waterfront after taking over his uncle’s business. He reckons he’s swung 10,000 compasses, and he’s still knocking them off. His business card proclaims him (without a trace of irony) the “Master of Deviation.”

Finally, late in the day, we drop the dock lines and steam over to Cruz Bay, on the U.S. Virgin island of St. John. We’re walking up the sidewalk when, without breaking stride, Murray bends over and picks up two crisp $20 bills lying in the street. “Look, beer!” he says, and moments later the currency is exchanged for a cold case of Dominica’s finest, El Presidente.

Yes, it’s hectic being the master. But it’s also good. Very, very good.

Cool. Steve Black, the founder and director of the Caribbean 1500, says that when it comes to high-seas sailing, there are few cooler customers than Black’s old Great Lakes racing buddy, Steve Pettengill-a veteran of the BOC Challenge solo around-the-world contest and the current chief of offshore testing for Hunter Marine-and Davis Murray.

“They’re just these warped guys who’ve never seen a day of bad weather,” says Black. “They could be out there on the worst day imaginable and they’d describe it as ‘fresh breeze.'”

Not surprisingly, Murray and Pettengill are also good pals who’ve knocked off a lot of miles together over blue water and black pavement. Murray keeps his 1988 custom soft-tail Harley alongside Pettengill’s collection of bikes in the latter’s Florida garage. The pair has been known to drop everything and bolt for Daytona, despite the fact that Murray believes his ride has serious front-end issues. “When you go past a bar, it always turns that way,” he insists.

Pettengill and Murray forged an alliance back in the late 1980s, when they helped deliver a mutual friend’s Whitby 45 from Chesapeake Bay to Fort Lauderdale. By that time, Murray had left the family compass-adjusting business in Philly, and his plans were, as they say, open-ended. So when Pettengill asked Murray to come up to Michigan to help him prepare his Hood 40, Freedom, for the 1988 singlehanded transatlantic race from Plymouth, England, to Newport, Rhode Island, Murray signed on.

It led to one adventure after another. Murray helped Pettengill deliver Freedom to the United Kingdom for the race start, then returned to Newport, which at the time was the growing U.S. hub of long-range solo sailing. He got to know Black, who’d raced his own Dick Newick-designed trimaran across the Atlantic, and started sailing with him on the New England multihull circuit. He also met an up-and-coming singlehander named Mike Plant and became involved with Plant’s Duracell campaign for the 1989 Vendee Globe nonstop sprint around the planet. Next up on the agenda was another project with Pettengill, namely his successful assault on the New York-San Francisco Clipper Ship record aboard the tri Great American.

In 1990, Black got the notion to form a cruising rally from the U.S. East Coast to the Caribbean, an event not unlike the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers that Jimmy Cornell had recently launched with resounding success across the pond. One of the first people he enlisted to the cause was his handy, knowledgeable friend, Davis Murray.

“He’s a wizard at problem solving, especially under way,” says Black. “He’s seen everything that can break on a boat.”

Murray sailed that first 1500 and each subsequent one as well, and they make up a goodly fraction of the roughly 170,000 nautical miles he reckons he’s accrued in his offshore career. Black usually pairs him up with a crew of fledgling voyagers on a paid gig that works out well for all concerned, especially considering that Murray handles the traffic on the morning S.S.B. radio sked and has walked fellow rally participants through countless underway repairs, from wonky electronics to failed rudders.

There’s no question that Murray has been a major asset to the rally, but the opposite is also true. For many years he boat-sat rally yachts at a marina in St. Thomas for owners who briefly returned home; he picked up plenty of repair work as well. It was then that he decided to make a permanent move to St. Thomas, from which he’s never looked back. More important to the telling of this tale, the Caribbean 1500 played no small role in introducing Murray to the guitar, a life-altering experience if ever there was one.

“A few years back, there was a guy from Colorado named Phil Robinson who did the rally,” says Murray. “He had a guitar on his boat. I come to find out he’s a pretty fine musician. One night we’re on his boat drinking Heinekens and I happen to mention how I always wanted to learn how to play the guitar. He says, ‘Grab a couple beers, I’ll get mine and show you how.’ So he starts me with a couple of chords, puts my fingers on the guitar and says, ‘Strum.’ He says, ‘Davis, you got rhythm,’ and that’s a good thing.

“Next time I’m in the States,” Davis says, “I buy my own guitar and start practicing. And practicing and practicing and practicing.”

Foxy’s. After a couple of crazy days in the U.S. Virgins, we end up, serendipitously, at Foxy’s Tamarind Bar on Jost van Dyke, in the neighboring British Virgin Islands, on the very evening of the iconic watering hole’s 40th-anniversary bash. There’s music in the air, and more on the way.

To that point, the mini-cruise on Splinter Beach, fueled by that initial case of El Presidente and a steady string of reinforcements, had been a rather riotous affair. We pulled into Norman Island and scrambled up Spyglass Hill for a bit of treasure hunting at the site of an old pirate’s lair, the inspiration for Murray’s tune “Dead Man’s Grave.” We had a glance at the beach on Virgin Gorda where he was married before 250 of his closest friends, and we also had a peek at several of the other local venues for the 75 or so weddings he’s personally performed. (Yes, you may also call him the Reverend Davis Murray, an online-ordained minister of the Universal Life Church, who-oh, let’s just skip it and move on.)

But for many reasons, Foxy’s is the perfect place to wind up the proceedings: The little beachfront bar perfectly personifies the endless connection between cruising, the sea, islands, the tropics, rum, and the music that fuses them all into a glorious whole. It’s a bond so strong and seamless that it’s sometimes hard to tell where one thing ends and the next begins.

Buffett, of course, has mined that vein for all it’s worth with a spectacular collection of songs and ballads, but there’s no end of talented, grassroots performers-folks like Eileen Quinn, Eric Stone, Derek Escher, Joe Colpitt, and, now, Barefoot Davis and his talented right-hand man, Morgan “Steel Pan” Rael-who have taken Buffett’s baton and are charting their own tuneful journeys along the watery way.

Colpitt, a singer and guitar player who sailed his trimaran, Virgin Fire, over from St. John, is on the entertainment roster at Foxy’s for the momentous occasion, and during his set he calls Murray up from the crowd to do a few numbers. The barefoot biker, guitar in hand, does not require a second invitation.

Davis Murray calls his music “island country.” And as with any good songwriter, his tunes are derived from the path he’s traveled and are picture windows into his soul. “South Cakalacky” is an ode to Charleston, South Carolina, and the time he spent there building a custom catamaran.

“Grape Jelly” hearkens back to his childhood in Massachusetts and the smells wafting from his mom’s kitchen. “Rum Is the Answer-What Was the Question?” recalls the playful banter between a charter captain and crew on a dayboat out of Red Hook, on St. Thomas. “Latitude 18” is a tribute to the St. Thomas gin mill of the same name where he began to find his way as a musician and still holds court every Monday evening as the house band.

But his most personal song may well be “One-Eyed Dan,” about a wandering soul who ends up in the Caribbean as a sailing troubadour, a mission he pursues right up to his dying day. Murray, of course, has two good peepers, but otherwise, the closing verse rings a familiar bell: “Though he lived his life with just one eye, he made it plain, you see; he seen twice as much as any man could ever see.”

Herb McCormick is a Cruising World editor at large.