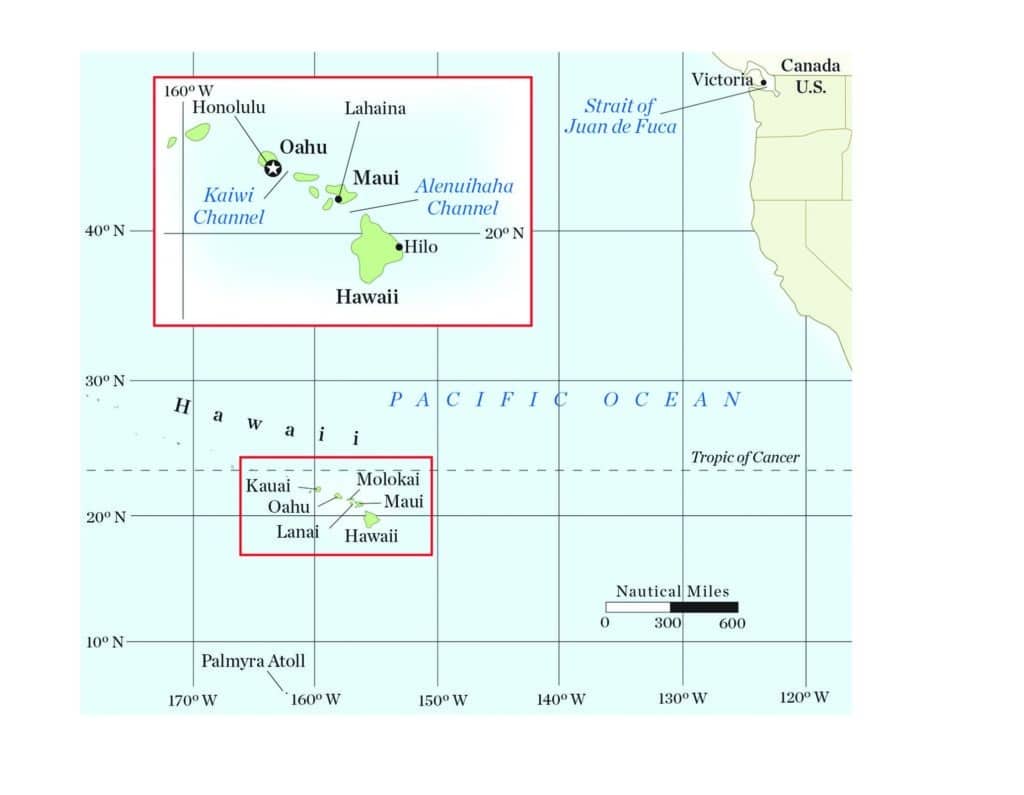

Timing a departure from the Strait of Juan de Fuca for the South Pacific via Hawaii is a challenge. If you leave too early you are likely to get hit with the last of the winter storms off the Pacific Northwest coast. The litany of lost seamen sustains this area’s reputation as one of the most dangerous bodies of water in the United States, if not the world. If you leave too late, by the time you have seen enough of Hawaii to make the passage there worthwhile, you are setting sail south into the fully developed hurricane season.

It was just off Cape Flattery, with steep, cold seas sweeping us stem to stern, that the thought crossed my mind that perhaps we’d left a touch early. But however humble, our 36-foot steel cutter, Roger Henry, is a robust little vessel and took the beating in its stride.

I did not. After a winter spent dockside with more sailing stories than sailing followed by a cruise in the placid waters of the San Juan Islands that was topped off with the café scene in the lovely city of Victoria, my stomach took a while to adapt to life offshore. As usual my wife, Diana, was chirpy and disciplined while on watch — deck tours, regular logbook entries, safety inspections and 15-minute horizon sweeps.

As we clawed our way south along the Oregon coast, I reread Jimmy Cornell’s World Cruising Routes. In theory, if we didn’t succumb to the temptation to head off on a direct rhumb line for Hawaii, but hugged the North American coast until the latitude of San Francisco, we would ride the clockwise wind patterns of the establishing North Pacific High. I felt better just visualizing all those glorious aft winds and following seas. But Jimmy does not give guarantees. He only advises as to averages, and alas, this was not an average year.

Against incessant headwinds we took nearly two weeks to reach an imaginary rounding point, 200 miles off San Francisco. But by then we were warm, together, and in that lovely cruising space where nothing exists except our little floating home adrift on a big blue sea. The global recession? What global recession? We have rice, water and wind. What more could a sailor ask for?

Our halfway-to-Hawaii party was a grand affair. Absolutely everyone came. We altered our watches so that we might share a few hours together. Ironically, at sea, in spite of being cooped up together in a small vessel, we each have our duties, among them sleeping when off watch, so we don’t enjoy much overlap. On our previous voyages we’d enjoyed lavish mid-route feasts, and once again we had just one celebratory drink and an unusually sumptuous meal together.

We saw but two ships in 2,500 nautical miles, but we never felt alone. On a late-night watch, two whales surfaced on either side of the boat, so close I could smell their fetid breath. They pressed in toward the hull and seemed to be cradling us up as if we were a fatigued calf. I was quite moved by that encounter, for their majestic mass can only be truly appreciated when up close and personal.

As the days passed, we sailed silently, scanning the horizon for signs of fish, porpoise, and perhaps a new species of bird — some lonely wanderers like ourselves, frightfully far from land. Sadly, however, we did not see the flocks of seabirds we have been used to in years past. Instead of being laden with life, the sea surface was littered with garish flotsam, marring the sense of pristine wilderness. In spite of its almost unimaginable 64 million square miles, the Pacific Ocean is showing significant signs of stress, and can no longer be used as an infinite dumping ground.

There’s a mental gravity that pulls one’s mind forward toward any large landmass. Though we were still many days out from Hawaii, our isolation bubble was burst. Diana began a tally of provisions required while I started yet another long list of maintenance chores.

The Big Island, Hawaii, loomed large in the morning sky. After 24 days of only blue, black and gray, the greenery was an assault on our senses, as were the pungent smells of a lush land laced with the sweet scent of frangipani.

All arriving yachts must check in at the small commercial basin called Radio Bay just to the south of the main city of Hilo. This is a closed industrial port, and since the Sept. 11 attacks any visiting sailors without a MARSEC Level 2 security clearance must be escorted to and from the front gate, no matter the time of day or number of entries and exits. When I heard that we were not even allowed to have visitors onboard, I found myself humming the tune “Don’t Fence Me In.”

Nevertheless, our stay was pleasant. We tied up and called the front gate from a dockside phone. Ten minutes later a uniformed woman rode up on a bicycle.

With a big smile she said, “Hello, I’m pretty.”

She wouldn’t get an argument from me on that score. But she meant Pretty with a capital P, her real name. She escorted us to Customs and Immigration, and then to the Port Office for registration. Everyone we encountered was welcoming and efficient. The Polynesians seem to have an innate sense of well being, expressed with open and humorous warmth. The office attendants were very helpful as they patiently explained how to catch the free buses to town, where to do laundry and how to find the main markets.

The next morning old sailing friends Mark and Dorothy Schneider of the yacht Dirty Dotty (we were told never to ask whence came that name) met us at the front gate. Over the next week they treated us to a guided tour of the spectacular Big Island.

It is said that there is no accounting for taste, but few would dispute that the Hawaiian Islands rank among the world’s most beautiful. Their latitude is tropical but temperatures are moderate. The surrounding seas are rich, and the high mountains and coastal plains create microclimates suitable to most types of agriculture. The prolific volcanic activity has resulted in fecund soil, no doubt lending to the success of the first human habitation, thought to have begun between A.D. 300 and 800. Theories abound as to a single arrival event, with Polynesians carrying pigs, dogs, coconuts, bananas and the now ubiquitous taro. Others state that migrations came in waves, mostly from the Marquesas. In any event, by the time of the first European arrival, perhaps as early as the mid-1500s, a large population with a sophisticated agrarian culture had developed.

Because any earlier European sightings or landings produced no surviving documentation, it wasn’t until 1778 that the intrepid explorer Capt. James Cook definitively and accurately placed the Hawaiian Islands, or as he named them, the Sandwich Islands, on the nautical charts.

Although now implacably within the American system of statehood, for nearly two centuries Hawaii was a colonial football kicked among England, France, Japan and even Russia for a period. Whaling and sandalwood logging were the linchpins of the early extraction economy. With their depletion, crops such as coffee, sugar, bananas and pineapples attracted foreign interest, leading to overwhelming immigration and eventual integration.

Today a mere 10 percent of Hawaii’s 1.4 million people are native or Pacific Islanders. But their influence is felt far beyond their numbers, for their sultry culture remains irresistibly seductive. With the welcoming floral leis, the soft strum of the ukulele and the swaying hips of the scantily clad hula dancers, as many as 10 million tourists per year see why Hawaii is dubbed “the Aloha State.”

We think of Hawaii as the eight main islands, the best known being Hawaii, Maui, Oahu, Molokai and Lanai, but outlying atolls and rocky outcrops extend the territory a full 1,500 miles into the mid-Pacific. This was of extreme strategic importance, as attested to by Admiral Yamamoto’s attack on Pearl Harbor on that “date which will live in infamy,” Dec. 7, 1941. That strategic significance has not waned due to the now internationally recognized 200-mile exclusive economic zone.

For cash-strapped sailors like me, the famed Hawaiian golf courses are officially exclusive economic zones, but not so the many beautiful national parks, the most dramatic being the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. Looking down into the glowing crater of Kilauea, I thought it rather ironic that while we are worried about a surface temperature rise of 2 degrees, nothing but a thin, brittle and shifting crust separates us from 10,800 degrees F of molten magma.

We ventured up nearly 14,000 feet above sea level to visit the Mauna Kea Observatories. As night fell, so did the temperatures, and we were soon huddled beneath every scrap of clothing and cloth we could find. The thrill was worth the chill, for this is one of the world’s premier stargazing sites, attracting scientists and astronomers from many countries and numerous universities and research foundations. Sailing and the stars are inexorably linked, especially for an old salt like me who relied on celestial bodies to guide my way across trackless seas. I was transfixed with the clarity of the powerful telescopes and captivated by the informative lectures and documentary films.

For an unstaged and authentic cultural experience, simply visit any one of the many morning markets, as we did in the old town of Hilo. These are colorful, vibrant affairs, where locals sort through mounds of meat, fish, baked goods and fresh produce to select their daily fare. Few leave without a basket or bouquet of tropical flowers.

With all this fresh produce so readily at hand, one is hard pressed to explain why Hawaiians lead the nation in per-capita consumption of a product that might seem to have an indefinite shelf life. Yet annually they enthusiastically devour 6 million cans of that succulent delicacy known as Spam.

Fascinated with maritime history, I have visited the site of Magellan’s great mutiny in Patagonia, the beach in the Philippines where he was murdered, the grave of Christopher Columbus, but most moving for me was the site in Kealakekua Bay, on the west coast of the Big Island, where the greatest seaman and explorer of his age, Capt. James Cook, was murdered. With the cyclone season approaching, we were forced to press on. After clearing Customs we departed the shelter of Radio Bay, and in the growing darkness sailed south along the east coast of the Big Island. On the coastline to our starboard the molten, blood-red entrails of the Earth flowed across the bleak volcanic plain and fell headlong into the steaming sea. We were witnessing nature at its primordial roots, engaged in a cataclysmic state of raw renewal.

Our disappointment with leaving such a beautiful necklace of islands was offset by the anticipation of an adventurous voyage 1,000 miles south to the remote atoll of Palmyra. My cruising motto could well be summed up as “anything atoll” because, although they are somewhat stark, I love their geographic structure and unique environment. Often atolls hang precariously perched on steep seamounts, making their outer coral walls steep, deep and dangerous. For free diving, there’s no more thrilling a challenge. Being so low, they are battered by the tempests of the sea, and I’ve literally felt them shake beneath the pounding forces of a wild surf. Occasionally swept abreast with storm surges, atolls offer little topsoil, and less potable water. Few people have mastered this harsh environment, thus many of the world’s atolls are deserted. This makes them prime locations for sensitive seabird hatcheries.

After seven brisk days at sea, we located Palmyra at dawn by the cloud of frigatebirds, boobies and terns swarming above the blue lagoon.

Palmyra is the last official “unorganized incorporated U.S. territory” — unorganized being the key word until recently. After a complicated series of political claims, Palmyra ended up privately owned but mostly abandoned since World War II. This lack of governance attracted developers, sailors, hermits and a few on the lam from the law, seeking profit, protection or privacy. Being exactly halfway between Hawaii and Samoa, its lagoon historically has offered welcome shelter for the few intrepid sailors passing though these remote waters, and with its coral tentacles extending well out to sea, it has hosted its share of shipwrecked castaways.

In the past, sailors heading north to Hawaii and not willing to comply with the strict animal quarantine regulations there abandoned pets to their fate on the atoll. We met one such dog whose heroic tale of survival was written upon his scarred body. Apparently, Dadu lived on rainwater and sharks he wrestled from the surf. The resident U.S. Fish and Wildlife staff feed Dadu now, but he still can’t help himself when he sees a blacktip shark swim by.

Abandoned cats had an easier time of it due to an infestation of nonnative rats. Ironically, it was the rats that posed the greatest threat to both the avian population and one of the largest remaining stands of Pisonia grandis trees in the Pacific, as they feasted on eggs, chicks and the seeds of the rare trees. In 2000, The Nature Conservancy purchased Cooper Island, the largest on the atoll. It has established a small but significant research facility there. Fish and Wildlife administers the remaining land areas and surrounding waters. In partnership they have refurbished the old World War II infrastructure, reopened the airstrip, cleared some trails and successfully eradicated the invasive rats.

Permits to visit are now required but easily obtained. Normally a yacht’s stay is limited to one week, and to protect the coral we were allowed to anchor in only one small, designated area. We were met at the entrance pass by U.S. Fish and Wildlife officer Amy, who informed us that we must radio ahead when we wanted to land on the island, and had to be accompanied if we wanted to venture into areas where ground-nesting birds were present. None of this detracted from a fascinating stay, and in fact, once Amy and the research station manager, Charlie, felt confident that we understood and respected the fragile nature of the environment, we were given nearly free rein.

We hiked through the green forests, occasionally rewarded with an ephemeral glance at the snow-white fairy terns. Tanklike coconut crabs scuttled through the dense underbrush as we poked out into the dazzling bright coastline, discovering deserted beach after deserted beach.

In peak season the year-round staff of four is joined by as many as 20 scientists. There is much to do, so they tend to pitch in and help each other with their projects. They wanted to do a spot count of four different bird species, which meant they needed every possible person with binoculars and bird books at the ready. Diana and I were asked to stay on an extra day and survey the outlying islands on the south edge of the reef. Walking and wading slowly and silently, we spent a serene day immersed in our own private wilderness.

Perhaps it’s the curse of the curious, for once again the open sea beckoned. With all sail set, Roger Henry slipped silently through the narrow coral pass and stood out on a course of south-southwest in a freshening breeze. A thousand miles over that watery horizon lay Samoa, the land made legendary by Robert Louis Stevenson. But wind and wave permitting, that would come in its own good time. For now we were just where we were, at home at sea, with time to reflect on yet another collage of indelible cruising memories.

Alvah and Diana Simon are presently cruising the North Island of New Zealand, their home waters.