The standing joke at the Alwoplast boatyard in Valdivia, Chile—the builders of my Atlantic series of cruising catamarans—goes like this: “Break out the umbrellas! Chris is coming to sea-trial a new boat.” So when my wife, Kate, and I recently landed in the town of Temuco to sunny skies, I was stunned. An hour later, however, as we turned off the Pan American Highway on the drive to the Pacific coast, the cloud deck worked lower and the raindrops increased with every mile. Ah, I thought, that’s better.

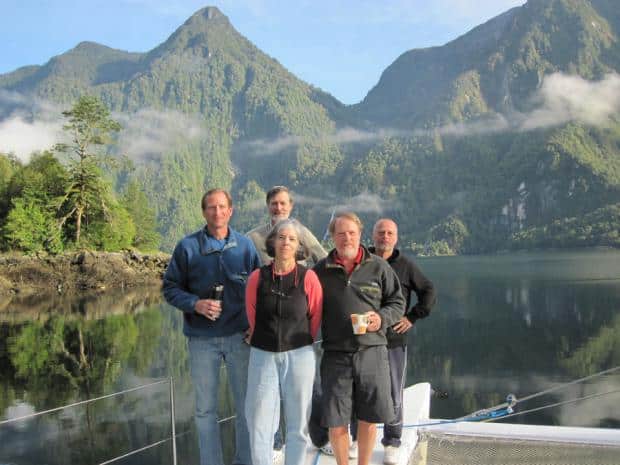

The plan was to board PataGao, a brand-new Atlantic 57 catamaran, with owner Jim Whalen and Alwoplast’s Alex Wopper and Roni Klingenberg, for a weeklong shakedown cruise in the spectacular cruising ground of coastal Chilean Patagonia. We eagerly anticipated sailing in a new region and sampling generous amounts of local seafood and wine.

For a month, Alex had been sending emails about the bleak El Niño weather and its near-continuous torrential rains with unseasonably strong winds. Though everyone had been looking forward to the cruise, I could sense the enthusiasm level receding with each report. February is normally Chile’s driest month, in the middle of the Southern Hemisphere summer, the prime time to enjoy a taste of Patagonia sailing. But it was looking like a washout.

Even so, at the boatyard, things were very much on schedule. Sails were bent on, electronics fully functioning, and engines and other systems checked out and operational. We agreed that early the next morning, we’d take a brief trial sail in the Valdivia River. If no problems developed and the weather looked OK, we’d make a break south the following day.

Our short sail in the river went well—it was sunny, and almost warm—and the weather forecast looked great for yet another day before strong northerly winds would close the harbor. In Chile, there are very few private yachts, and the Chilean national navy regulates their movements. You must obtain permission to move from port to port, and when the navy has doubts about the weather, it closes the harbors in the interests of safety and won’t allow anyone to leave. This seems a bit heavy-handed to me, but those are the rules. The coastline is very rugged, with long distances between safe harbors, and frequent gales. In any case, if we jumped on it, our cruise could begin immediately.

Valdivia is one of the best harbors in southern Chile, and in the days of yore, it was the first town where square-riggers coming north from Cape Horn could refit and provision. Today, Alwoplast Marine serves many yachts of all sizes in their preparations for southbound journeys. The prime cruising ground starts about 120 nautical miles south, where the monolithic coastline gives way to thousands of miles of islands, channels, and glacial fjords that allow inside passage most of the way to the Horn. Both Alex and Roni have sailed extensively in this region and would rather be here than anywhere else in the world. It was a treat to have such good local knowledge on board.

With a crisp land breeze and the scent of pine trees in the air, we set forth, but once we were clear of the river, the breeze vanished. Oh, well, part of our mission was to uncover what didn’t work before Jim and his crew departed for the Galápagos Islands and Panama in a few weeks. So on came the engines, and we powered south along the rugged coast.

Like her sisters, PataGao motors very well; she’ll do eight knots on one engine and 10.5 knots running both. Our goal was to get into the Canal de Chacao, about 100 miles south, before the forecast northwesterly filled in. This channel is about 10 miles long and a mile and a half wide, and it separates the large island of Isla Grande de Chiloe from the mainland. The rub here is that the tidal current can run at 10 knots! When it’s blowing hard, it creates overfalls that have rolled large ships. Roni had seen it in an ugly mood and didn’t savor a repeat experience, so there was some urgency to knock out that first leg quickly.

During the course of the day, the wind built to 20 to 25 knots, but it was right on the nose. The wind-induced chop on top of the eight-foot swell made conditions a bit rough, but PataGao—Portuguese for “big foot,” the original name that Magellan supposedly bestowed on the natives of Patagonia—was maintaining a very comfortable eight knots at cruising rpm, so we kept motoring in an effort to reach the canal before the westerly shift. Other than a few whales and a tugboat steaming north, we saw nothing afloat, just the mountainous wall of coastline mostly covered with evergreens, with an occasional glimpse of a snow-capped volcano in the distance.

It was well past sunset when we entered the Canal de Chacao. The wind had eased, and the fearsome conditions were only hinted at in great swirls of water and current rips—clear enough warnings to experienced sailors to watch and be wary. Roni piloted us into the anchorage on the northern shoreline at Carelmapu, where we could anchor for the night among the commercial fishing boats and wait for the morning’s favorable flood tide.

The next morning, we continued eastward through the channel. The northern tip of Chiloe was to starboard as we passed two navy vessels trolling for wreckage from a recent ferry sinking. The favorable current was running at about six knots. Great big eddies were marked by diving birds and numerous seals and penguins fishing up a storm.

Entering into Bahía de Chacao, we turned right down the eastern side of Chiloe, which is about 100 miles long and sits some 30 miles off the mainland. Sailing along its beautiful, serene shore, we saw scenery reminiscent of Maine or Nova Scotia: numerous islands and coves, and rolling hills and pasture with an occasional farmhouse. But when we looked east across to the mainland, the sight of the snow-capped Andes with smoking volcanoes interspersed between the craggy, 15,000-foot peaks was evidence that, figuratively speaking, we weren’t in Kansas anymore.

Alex and Roni—both incredibly intelligent, multilingual, and, most important, fun to hang out with—are quite a pair. The founder of Alwoplast, Alex built a cruising boat in Germany as a young man and took off around the world. He fell in love with the wild regions of southern Chile and settled in Valdivia some 25 years ago to make a living building boats, gradually working up in size from Tornado racing catamarans to a variety of commercial and pleasure cats, both sail and power.

Now that the boatyard has grown to employ 50 people, Alex runs the business end of things and his right-hand man, Roni, manages the shop floor. Born and raised in Chile of German descent, he’s an engineer by disposition as well as formal education and a born problem solver. One seldom sees him without his head buried in an instruction manual or performing mechanical surgery on a piece of faulty equipment. It was a great crew to have on board a new boat for a shakedown cruise, especially because, as we all know, new boats can have some gremlins.

Our first anchorage in northern Patagonia was at quiet Isla Mechuque, part of a cute group of little islets offering many protected bays. The weather was overcast and raw, so we all were content to sit inside the heated pilothouse and watch the 12-foot tide slowly recede in our little cove. The next morning, a fellow in a small rowboat came alongside and asked if we’d like some shellfish. Why, of course! Thirty minutes later, he came back with a huge bucket filled with a variety of mussels of different sizes and three types of clams. He was all smiles when we happily agreed to his modest asking price, the equivalent of just a few U.S. dollars.

The day was clear and provided a fine sailing breeze, so we weighed anchor and continued southwest toward the small but vibrant fishing and farming town of Dalcahue, on Chiloe, about 20 miles away. Alex was keen to show us the Saturday market, and though we were well provisioned, it was hard to resist buying lots more of the incredible local fare: smoked salmon and mussels, sun-dried clams, edible seaweed, local cheese, delicious corn, unusual varieties of potato, and all manner of vegetables. Cruising in this region of Patagonia is definitely not part of a weight-loss program.

The following day, we worked farther south along the eastern side of Chiloe, zigzagging through a long maze of narrow channels with beautiful and varied views of forests, farmland, and many fish farms. While the boating is spectacular in this region, the sailing is often marginal. The long, narrow channels, banked by high ground, makes what wind there is choppy and typically either dead ahead or dead astern. Throw in two- to three-knot tidal currents and you have waters where motorsailing is the sensible way to travel much of the time. Since cats motorsail so well, with decent speed and very good fuel economy, they’re well suited to the area.

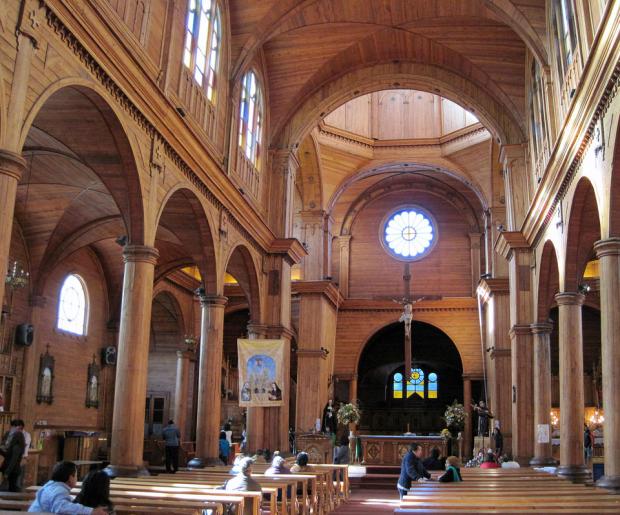

Our goal for the day was Chiloe’s main town and the region’s capital, Castro. Because of the significant tidal range, the waterfront buildings there are constructed on very tall stilts, giving it a unique appearance. After we anchored off the town late in the afternoon, the crew was eager for a walk and a chance to check out the activity. The first stop was to run the gauntlet of seafood stalls along the waterfront, sampling the local oysters and other treats, but the most pleasant surprise turned out to be the famous church in the town square. Built of wood with numerous vaulted ceilings, it was definitely a boatbuilder’s cathedral.

We would’ve enjoyed hanging out in Castro, but we had a schedule to meet, so we kept moving. It took 30 miles of motorsailing to reach open water in the Golfo de Ancud. Once we were beyond the shadow of the hills, the breeze filled in. The day was crystal clear, and finally PataGao had a chance to stretch her legs on a deep reach. We made 10- to 14-knots before a 20- to 25-knot breeze, and 50 miles flew by.

Our destination that day was Fiordo Quintupeu. Since Alex or Roni had said little about it, the three gringos on board had little idea of what to expect. As we closed on the Andes over the course of the afternoon, the anticipation built. Eventually, a small slot opened in the near-vertical green wall ahead of us. From a distance, it was hard to get a sense of the scale, but inside the little opening was a fjord, which revealed itself as we sailed through the gap in the clear afternoon light.

It was my second religious experience in as many days.

With the exception of Somes Sound in Maine, I’m a fjord virgin, but this place was very special. If you could sail a boat into Yosemite Valley, the experience would be similar. The waterfalls were huge, wild, and stunning. No one on board could utter a word. And this was just the northern tip of a wilderness that stretches southward for another thousand miles to legendary Cape Horn.

Eventually, we came to our senses, dropped the hook in 75 feet of water—anchoring in 500 feet in the fjord’s center wasn’t an option—and ran three lines ashore in the dinghy. That evening’s sunset and morning’s stunning light were beyond my ability to capture with words.

Finally, the long stretch of clear weather was coming to an end. High clouds approaching from the west obscured the sun, and the forecast was for rain and strong winds. Our time was running short, so we made the long daysail north to the busy commercial port of Puerto Montt, where we’d dock PataGao until it was time for her to return to Valdivia.

Looking back on the trip from a cruiser’s perspective, my own preference is for warmer places. And Patagonia is far away; sailing your own boat there from any port in North America would be a rigorous, time-consuming affair. The first part of the trip was fun and interesting, but with slight modifications to names, places, and foods, I’ve cruised similar areas before.

But the fjord opened my eyes to the strong attraction Patagonia holds for many sailors. Looking southward on the chart and imagining the empty, pristine, and beautiful cruising grounds, it’s impossible not to want to keep heading in that direction. Certainly the farther south you sail, the wilder the conditions. The williwaws can be unsettling, if not dangerous. Anchoring in many places is insecure and a challenge. But if it becomes too much at any point, you can spin northward to more temperate conditions. It all seemed doable.

Will I ever take the time to sail my own boat back for a cruise? Probably not. Few people do. However, having a new boat built 100 miles from Patagonia practically demands that you stay there for at least one season to savor one of the world’s most spectacular cruising grounds.

I can’t wait to do it again sometime.

Dedicated to the creation of safe, comfortable, high-performance cruising multihulls, yacht designer Chris White has continuously refined his work over four decades. When not sailing Javelin, their Atlantic 55 cat, Chris and his wife, Kate, the parents of two grown sons, reside in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts.