“Willie, call me as soon as you can. I bought a boat. I haven’t seen it yet. It’s in the middle of Florida. We have to get it out of the boatyard by Monday.”

When I received the voicemail, I was racing a Melges 24 regatta in Miami, and I knew adventure was brewing. My father-in-law, Chris, had started with casual boat browsing online and progressed to the sight-unseen purchase of La Reine, a 23-year-old Beneteau 381. In the process, he had set in motion a journey that would take my wife, Kim, and me on a 50-day, 1,000-nautical-mile shotgun journey into the unknown.

Starting with getting the boat off the hard for him within three days.

Two days later, I got my first sight of the boatyard where La Reine was waiting. Row upon row of deserted boats covered in various shades of mossy growth stretched as far as I could see. Imagination turned to panic as I drove past the first derelict hulls and pulled through the front gate.

As I entered the boatyard, heads popped out of companionways covered in fiberglass dust and paint. The boats in this part of the yard were notably more seaworthy, and a ragtag crowd was lovingly working on them.

La Reine had a fresh coat of paint that made her shine, and a suite of new electronics gave her a modern feel. As a professional racer who has seen my share of collisions and repairs, I was very aware that the shiny new cosmetics might mask something far more daunting. I pushed the possibilities from my mind and set to work.

The Caloosahatchee River makes up the western stretch of the Okeechobee Waterway, which connects the tranquil Gulf waters of Fort Myers to the Atlantic Seaboard at Port St. Lucie. We had not yet been able to secure a reservation in a marina on either coastline, so the plan was to take the boat a few miles downriver toward Fort Myers, and then leave her in Port LaBelle Marina to buy ourselves enough time to install safety gear and make a game plan.

That afternoon, one other boat was ceremoniously hoisted from its resting place in the yard in preparation for an adventure at sea. The excited young couple had spent the past two years on the hard fixing leaks, working on the engine, refitting plumbing, and everything in between. Briefly, the thought crossed my mind that La Reine should spend a few more months in the yard to go through all the systems, but it was too late for that. Whatever issues the new paint hid would be revealed soon enough.

After a three-hour round-trip drive to Fort Myers to acquire provisions for my first night on the boat, I returned to find that the stove wouldn’t light, so my quesadilla dinner became a cheese and tomato wrap. After dinner, I discovered that the toilet wouldn’t flush, thankfully in time to head up to the marina bathrooms.

Kim arrived early the next morning. After a pit stop to purchase parts, we started up the diesel on the first try. Our adventure was underway.

The first day was smooth motoring. Kim navigated the canal, and I watched YouTube videos to learn how to dissect the plumbing. As I wrapped up installation of a new pump and valve, we arrived at our first lock. The friendly lock operator walked us through the procedure, and the conditions were calm, making the process easy. When we were ready, the back gate closed, the front gate cracked open and dropped the water level 14 feet, and we were on to the next section of canal.

At Port LaBelle that evening, we were greeted by an alligator floating lazily past the entrance. We cut the drone of the diesel, so the only sounds left were nature: plentiful bird life and the distant moos of cows. It was the quintessential Southern evening. We still didn’t know where we were headed, but for the next few weeks, this would become our launch pad for the projects needed to make it to the ocean, and whatever lay beyond.

We had only a few short days in Port LaBelle before I had to head back to work for a week, and Kim had a trip planned with friends. We crammed in as many projects as possible, with the expectation that we’d be headed to the ocean the next time we saw the boat.

When we returned to Port LaBelle, Chris had settled on a summer marina at Jekyll Island, Georgia. Meanwhile, Kim and I were plotting a one-month detour through the Bahamas. We would head east on the Okeechobee Waterway, then south to Miami and up through the Bahamas, then to Georgia. We didn’t have any marina reservations, but we felt that there was no better way to get to the top of the waiting list than to show up.

As soon as Kim arrived, we transferred a mountain of boxes we’d ordered online from the marina office onto the boat, and we bid farewell to Port LaBelle. With a nice following wind, we unfurled the jib for the first time and retraced our tracks from only a week before.

After about an hour, we arrived back at the lock that we had previously dropped down and prepared to float back up. “Ready?” came the voice of the operator. We thought we were.

As the back gate closed, I noticed that the fenders were slightly too far apart. The freshly painted rail of La Reine came to rest just inches from the cement wall as the front gate opened and water rushed into the lock. The boat seesawed at the mercy of the floodwaters.

With my gaze fixed on the tiny gap between the rail and the wall, I wrestled with the dock line, fighting to avoid grinding off the fresh coat of paint. Minutes seemed like hours, but eventually, the water calmed and the boat came to rest. Miraculously, the rail was unscratched.

For the rest of that afternoon, we motored lazily up the canal, past Glades Boat Storage and up the river to Moore Haven, where we spent the night on the city dock.

The morning was full of beauty, with golden sunlight pouring down on swampy vegetation and animal life. Alligators, turtles, lizards, and birds of all varieties seemed to wake with the sun and escort us down the next stretch of the ditch.

By late morning, we passed through Clewiston and reached the entrance to Lake Okeechobee, where we set a course through the narrow channel. By noon, land slipped from sight and the wind built to the midteens. Our jib was deployed, and our adventure seemed to be in full force.

Kim was at the helm when the steady, rhythmic knocking of the diesel began to fade. At first, I thought one of us had bumped the throttle, but power quickly faded to an idle thrust. I spend a lot of time around outboard engines in my job as an Olympic sailing coach, but the diesel was a new beast. This felt like a gas issue, but the gauge read three-quarters full.

Kim turned us head-to-wind while I hoisted the main and cut the engine. The wind was puffing at nearly 20 knots and, luckily, carried us downwind toward the far lakeshore, but we knew we would need the engine to get through the lock on the far side. Kim drove while I went below to put on my mechanic’s cap.

After about an hour, I had drained some sediment out of the fuel filters. I was cleaning out the air-intake manifold when Kim called down: “I can see the lock getting closer. The waves are getting bigger. What are we going to do?”

I poked my head back up. The channel markers for the lock were getting close.

We cranked the engine, throttled up, and La Reine plowed forward.

“Sails down and fingers crossed—all we can do now is hope that it doesn’t die again,” Kim said with a worried look.

We hailed the lock operator. The wind was now blowing a steady 20 with a lumbering, lumpy chop. The lock operator came on the VHF radio: “Conditions are rough, but it’s not getting any better. Let’s get you through. When you get inside, let me close the gate before you go to the wall so that the chop can die down.”

If the engine died now, we’d have major problems. We carefully nosed into the lock, with the boat pitching wildly from the chop.

“Be ready with a mobile fender in case I lose control,” I told Kim.

As the gate swung closed behind us, the engine held, but even with full power, I was fighting hard to keep the boat under control. The bow swung left, then right, at the mercy of the wind, so I tried to keep the stern centered to buy enough time for the chop to subside.

“That’s it,” came the voice of the lock operator. The chop was still big, but we were fully committed, so I took a deep breath, tried to relax, and waited patiently for the bow to swing. As the next puff took hold, the boat rotated 20 degrees, lining us up for a nice approach to the wall. I hit reverse, praying that the engine would hold just 60 seconds longer.

In the end, it was one of our smoothest lock passages. While the lock operator commented on our excellent boathandling, I told myself, Better lucky than good.

I started to relax as we exited the cement box into the tranquility of the canal on the other side, but no sooner had we passed the final gate than the bridge ahead stole my focus. This 49-foot railroad crossing controlled the navigational height east of Lake Okeechobee.

We radioed the operator for a final check on water-level height. When we told him we were 48 feet tall, he replied, “Don’t quote me on this, but I think you’ll probably make it.”

The adrenaline took hold again.

Back at Port LaBelle, I had gone up the rig and measured that we should have a foot of clearance above our mast, but seeing the bridge in front of us, my imagination ran wild. I envisioned a westbound motorboat trying to squeeze through the bridge at the same time as us, with its wake bouncing us into the top of the bridge. We figured that every inch mattered, so, using a hammock, we rigged up a seat for Kim on the end of the boom. As I swung her out over the water, the boat heeled 5 degrees to starboard. I had calculated that this should buy us 6 extra inches of clearance.

We went as slowly as possible, with the hope that impact at these speeds might give us a chance to save the rig, but the approach was agonizing. Hanging over the water, Kim worried that she might have a date with an alligator if things went south.

At the last moment, I threw the boat in neutral. As we glided smoothly through the crossing, I looked up. Was it just me, or was the antenna on top of the rig tickling the bottom of the bridge? No, just my imagination. Elation. We were through.

We laughed and smiled and felt like heroes. We had avoided the lengthy western route through the Keys, and the sun was shining.

We didn’t notice the first few raindrops. All afternoon, I had been tracking the cumulus development to the north, and while the fluffy white pillars had grown into thunderheads, the radar showed no sign of southern movement. While we’d been preoccupied with the lock and the bridge, though, the system had veered sharply. Within minutes, I found myself diving for my foul-weather gear in pelting rain.

No sooner was I dressed than the engine died again.

Kim rushed below to grab the windlass controller. The crackle of thunder and lightning in the distance was getting closer. I swung the bow head-to-wind in the lee of a thicket of trees and, with the last of our momentum, did my best to estimate the swing of the boat in the narrow canal.

“Drop 20,” I called, glancing at the depth gauge. Kim put down 20 feet of chain as the boat started backward.

With the anchor set, we scrambled below and closed the hatches to wait out the rest of the squall and continue working on the diesel.

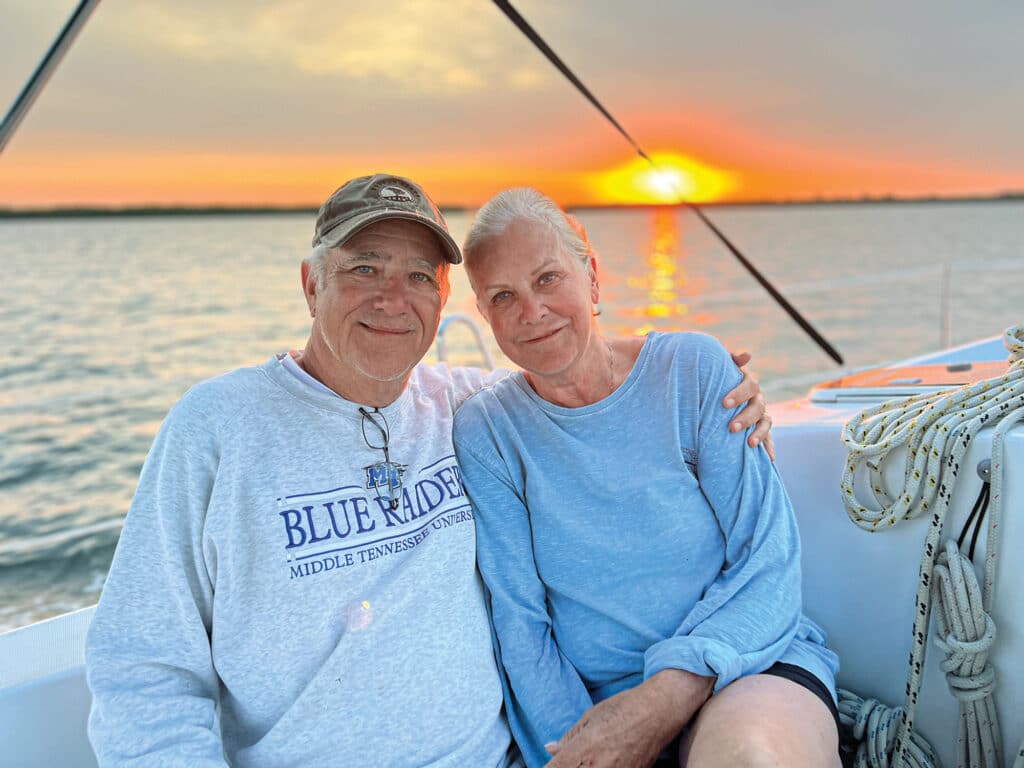

Later that evening, La Reine slipped down the glassy canal as the towering cumulus above the forest reflected golden oranges contrasting with ragged, dark grays. La Reine’s diesel, alive once again, buzzed gently under my feet. The air was still thick from the rain, but it was cool now that the storm had moved off into the distance, having washed away much of the sweat, grease and stress that marked our first big day of delivery.

As we pulled into a slip just before the final lock of the trip for the night, I was reminded that man plans and God laughs. Of all the scenarios I had run through in my head, the leeward shoreline lock with a dead engine had not been one of them.

The next day, we headed for the Atlantic. We geared up, tethered in, and headed out of Stuart in a beautiful 15-knot northerly for La Reine’s first true sailing test.

The first hour was all smiles. We surfed the waves, reaching and winging our way down the coast. Through the afternoon, the breeze built and more rolling waves began to make Kim feel sick, so we set a course for an inlet a few miles down the coast. Before we could make it to the calm water, however, we heard a popping noise, and looked up to find a large hole in the luff of the main. A seam of old stitching had given out, and rotten threads on either side looked ready to give way too.

The mainsail blowing out wasn’t something that we could have predicted, but as soon as it happened, we made the best of the situation. Kim took the helm and spun us into the wind while I reefed the main to the second reef point. This confined the hole in the sail to the folds of the reefed slab, allowing us to continue down the coast at a good pace as we motorsailed to Hillsboro Inlet at Pompano Beach.

For the next few days, the clear-blue Miami water replaced the murky green twists and turns of the Intracoastal Waterway, and we began to feel one step ahead. As we wound our way through the juxtaposition of wild nature and intensive urban development, we were able to secure a mooring ball, schedule a mechanic to service the engine, and book an appointment to have the boat sized for a Bimini top.

In the final stretch, we navigated intense Saturday traffic in Miami: lavish yachts, loud music, and crazy chop from reckless boaters. As we turned into the calm waters of Dinner Key Marina, sweet relief washed over us.

Champagne in hand, we video-chatted with Chris, telling him we’d made it and that La Reine was in one piece. We spent the rest of the evening reliving our endless snafus, laughing and smiling. It was amazing how much life we had lived in just four days.

What had we learned? No matter whether you order your boat new or find one online, plans will eventually fail. And when they do, the real adventure will begin.