The mid-May sun was surprisingly hot as we spun into the wind, idled the engines, and hoisted the big roachy main aboard San Fredelo II, the Sunsail 404 catamaran that would be home for the next five days. Next, we rolled out the genoa and bore away to a beam reach, leaving provisioning chores, briefings, crew introductions and the Marina Agana astern.

Sailing, at last—in Croatia. A longtime entry on the proverbial bucket list was about to be scratched off as my sailing pal and trip organizer, Josie Tucci, vice president of marketing at Sunsail, steered us eastward and out of the narrow bay toward open water dotted with islands. Near the helm, her brother, Jason, and I trimmed in the sheets and tidied up as we began making way. To port, I could see cars on the coastal highway, headed north from the international airport in Split. To starboard, the rocky, brush-covered shoreline rose to meet a sky that was fairy-tale blue. Already, my colleague, photographer and drone junkie Jon Whittle was snapping away. How could he not? The sights were otherworldly in this centuries-old corner of the Adriatic Sea.

Around us that Sunday morning, the crews aboard nine Sunsail monohulls were going through similar drills, as one by one they raised sails and pointed their bows toward Milna, on the island of Brač, the flotilla’s first-night destination, where a gin-and-tonic reception awaited us.

I’d never sailed in a flotilla before, but already, less than a day into it, I was enjoying the concept of exploring a new destination with a helping hand, if you will. Earlier that morning, after a buffet breakfast of eggs, sausages, fruits, and doughnuts at the marina’s restaurant, skippers, and crew gathered in a shady spot to meet Sunsail’s flotilla captain, Samantha “Sam” Algero; hostess Ellie Riccini; and “Drago,” the team engineer. This trio would be on hand to assist and advise 24/7. When it was time to go, they’d be the ones handing us our dock lines. And when we arrived at a new location, their boat, Hvar 1, would already be tied up. They’d be waiting to take stern lines as skippers nervously (at first, anyway) backed in to moor stern-to at each new village.

“Slow is pro,” Sam reminded us frequently the first few landings.

Ellie too dispensed practical info. “Keep the boats tidy,” she urged. “A tidy boat is a safer boat.” And, “Beware the sea urchins.”

At that first briefing, Sam and Ellie outlined the week ahead: daily skipper meetings at 0900, lunch where you like, and each evening a different destination with a suggested time of arrival. At night, there were organized events to attend—or not. Wednesday, we were free to sail wherever we liked, so long as we all regrouped in time for dinner on Thursday.

They went over the fine points of Lateral Navigation System A (red and green buoys are opposite where they would be in the United States), safety issues, and local weather to watch. The bura is a gusty northeast wind that brings clear conditions. The jugo: southeast breezes with rain. The maestral northwesterlies tend to build in the afternoon.

And these words of caution: “If you didn’t eat it, don’t flush it.” Holding tanks were to be emptied 2 miles offshore, and there was a 100-euro fee to fix a clogged head.

Alrighty, then. Duly warned.

But best of all, their review of the charts greatly simplified finding the Croatian place names that were difficult to pronounce, tough to understand, and even harder to spell.

Off to the Islands

Josie, Jason and I had spent Saturday afternoon provisioning at the nearby Tommy’s market. For a few coins, you could borrow a shopping cart to deliver groceries to the boat. We stocked up on lunch meat and breakfast fare, Croatian wine, and Ožujsko, a local beer. That evening, we had dinner at the marina and sat on San Fredelo’s tramp watching the moon rise over the opposite shore. The water was still, and the reflection of the square stone tower at the head of the harbor was crystal-clear.

Sunday turned out to be a perfect day to regain our sea legs, with a northerly breeze in the midteens sending us on our way. We stopped for a late lunch and anchored in the pretty little harbor at Stomorska, on Šolta, a point that was about halfway into our 18-nautical-mile sail. The anchorage allowed an imposing view of the towering mountains that rise above metropolitan Split. Ashore, a handful of fishing boats sat idle, and we saw but a few folks moving about amid the distinctive white villas with red-tile roofs.

From there, it was an easy run to Milna and the Marina Vlaška. As Josie backed the cat toward the quay, Jason and I stood on either transom with boat hooks in hand. We handed our stern lines ashore, and the Sunsail team held up bowlines for us to grab and take forward. The ropes are sunk when not in use, and are led from shore to anchors in deeper water. It was an amazingly drama-free operation.

Once we were settled, we grabbed swimsuits and found a nearby rock from which to jump. The seawater was cool but refreshing, making a hot shower at the marina afterward feel all that much better. Then we headed up the hill, past olive trees and stone terraces, to claim our gin-and-tonics, and to chat with other crews as they came and went.

At sunset, we walked a mile or so along the shore road into town. On the way, we passed a street vendor and stopped to buy four garishly colored Croatia ball caps that quickly became our team hats. In the town center, a large, weathered stone church was lit up, along with other ages-old buildings. Behind them, we spotted more steeples draped in light. We found an open table at a small pizzeria and washed down our slices with tasty local wine.

Of course, we posed for photos with the colorful, whimsical ice-cream-cone statue we passed on the way back to the boat.

Relic of War

A look at the charts reveals that along this part of the Croatian coast, long, thin, mountainous islands run roughly west to east from the open Adriatic, as though some ancient creature drew fingers though terra firma, allowing the sea to run in between.

On Monday, we didn’t have a lot of wind as we motored out of Milna and turned southwest to navigate the channel between Šolta and Brač, and turned again southeast to follow the coast. We passed numerous marine farms and inviting anchorages, but we’d already decided that our lunch-stop destination would be a small bay a few miles south, where a submarine base dating back to when the country was part of Yugoslavia is carved into the hillside. Once we’d found the cove and anchored, we launched our inflatable and took a ride inside the long, narrow tunnel once used by naval vessels to avoid detection. Rather than seeing warships, we found cool relief from the sun-splashed bay. Today, fishermen use the rock-lined safe haven to tie up their skiffs. During our visit, there wasn’t a soul around. Instead, small birds darted about, their shrill chirps echoing off the rock walls.

The cove was quite protected. As a few others in the flotilla fleet arrived and dropped anchors, we took turns exploring on the two paddleboards we’d brought along.

That afternoon, a lazy breeze picked up from the northwest, and San Fredelo ran before it as we headed for the harbor at Jelsa, on the island of Hvar, across a body of water marked on the chart as the Hvarski Kanal. After a morning of motoring, all aboard welcomed the sail, but the dead-downwind heading proved both crash-jibe prone and slow. Eventually, we kicked on the motor again to make the harbor in time for a 1600 tie-up. After all, wine and hors d’oeuvres at a waterside restaurant, organized by Sam and Ellie, awaited us.

Jelsa lies near the midpoint of Hvar’s north shore. Its harbor is a relatively square body of water, protected by stone jetties. Wide, flat stone walkways around the waterfront give the place an open plaza-like feel. When we arrived, several flotilla boats were already tied stern-to, but Capt. Sam directed us to an open spot, and her crew scrounged up a plank for us to use as a passerelle.

The restaurant, the iconically spelled Me and mrs Jones, was on the far side of the harbor. Our stroll there took us past palm trees and weathered stone buildings—some white, others a faded pinkish color. Inside the restaurant, the front room had been cleared out to make space for a table covered with wineglasses, carafes of red and white wine, and trays piled with appetizers made with anchovies, shrimp, and assorted meats and cheeses. Soon, the stone-block-lined room was packed.

After an hour, the crowd thinned and the staff began setting tables for dinner. Jason and I took a half-empty carafe of red and sat at a table outside with a couple from the flotilla who were sailing aboard a Jeanneau 34. Steve was from England, Josephine from Hong Kong. Prior to the pandemic, these longtime friends would meet at various locations around the world for sailing vacations. This was their first time together since the global shutdown. They planned to keep the boat at the end of the week, and sail up and down the coast a bit longer. Like sailors everywhere, we talked about weather, memorable voyages and, of course, our current adventure, which they were finding to be quite social compared with their usual visits to quiet, remote anchorages.

As we were about to leave, a pair of women rode up on bikes and sat at the table next to us. They pointed to the road winding up the towering mountains that form a spine atop Hvar and said that they’d just come over them from the other side of the island. No wonder they were ready to sit down and quench their thirst.

That evening, we strolled up into the hillside town from the waterfront. The stone streets were polished smooth by centuries of foot traffic, the narrow lanes between buildings too tight for cars. The sounds and smells from the open-air Konoba Nono restaurant were irresistible. Its barbecue was excellent, and we topped it off with glasses of rakija travarica for dessert. The strong-tasting liquor, often made of plums and herbs, is a Croatian delicacy and must at least be sampled, in my humble opinion.

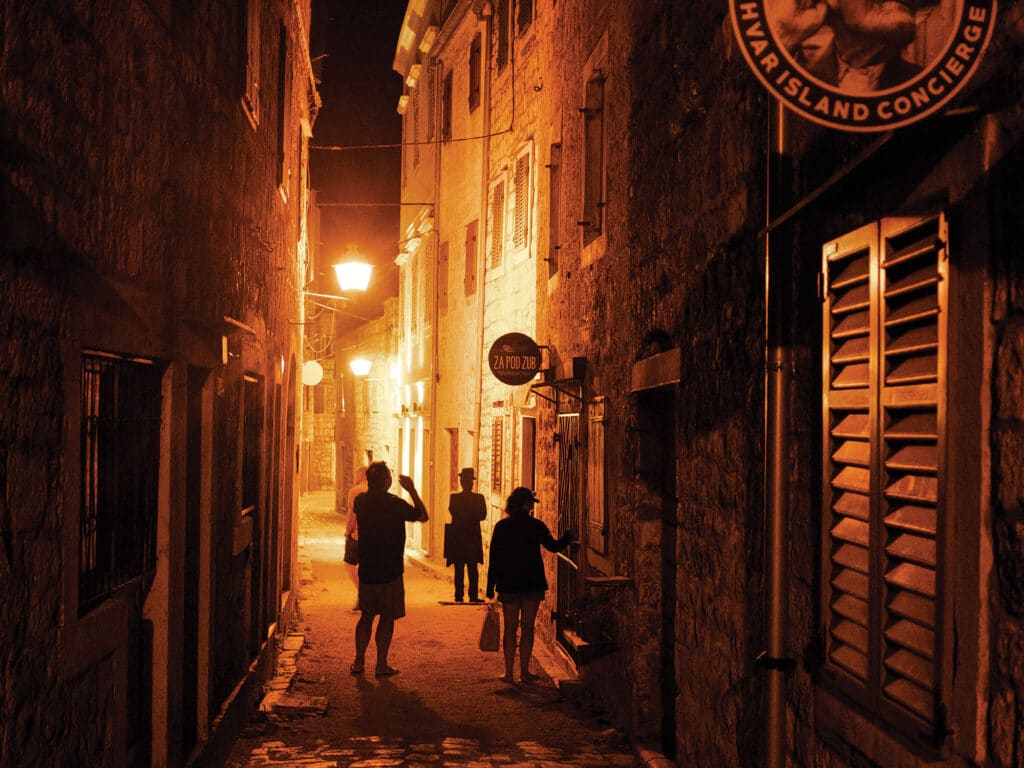

I say “sampled” because in abundance, it can lead to unexpected consequences. After dinner, Jason returned to the boat while Jon, Josie and I continued to explore. Our ramblings took us past age-old churches and through tight, twisting alleyways, past homes with laundry left out to dry in rocky courtyards. Eventually, our footsteps led us to a tavern, which led to Croatian beer and then more rakija. We were left spellbound by the sweet folk melodies that a woman named Anna and her male vocalist partner sang as they leaned against the bar, drinks in hand. When the bar closed, we lingered outside, talking with the singers. He had to work in the morning and said goodbye. Anna? Well, we followed her to the small bar she owns and sat talking until dawn, then went with her to watch the sunrise from a beach.

That’s the thing about a sailing trip to Croatia. The people are as warm and friendly as the islands are lovely. It was easy to strike up a conversation with just about anyone. Most Croatians we met spoke English. Every storekeeper had a smile. The owner of an olive shop, recommended by a waiter and contacted by phone one evening, agreed to open early the next morning so that we could buy delicacies to take with us. Strangers couldn’t wait to tell us why we had to visit their favorite spot. Everyone had one. It’s easy to fall for such charms.

Off On Our Own

It’s perhaps not surprising that we were the last boat off the quay Tuesday morning. Not to worry—we had just a 12-nautical-mile hop to the west along Hvar’s north coast to reach the protected bay off Stari Grad, one of the oldest towns in Europe. The little wind we had as we left Jelsa was on the nose, so we chose to motor instead of sail. It was yet another lovely little adventure on the water, complete with dolphins. Across the channel, the mountains on Brač were a patchwork of earth tones and greens, the hues of olive trees and gluhi bor, a black pine that covers the arid landscape. Ferries crisscrossed the channel, and we passed numerous small fishing boats and saw flocks of birds working the water roiled by baitballs off in the distance.

By 1430, we were tied up to yet another stone quay in a snug harbor surrounded by a bustling town. We moored just in front of the town’s municipal showers, which were handy. From there, Jon and I walked a half-mile or so along the quay to restock at a Tommy’s market, and then met the rest of our crew for a late lunch.

Back at the boat, we sat under the cockpit Bimini top in a feeble attempt to evade the stifling afternoon sun, and chatted with the crew aboard the flotilla boat moored next to San Fredelo.

We dined ashore that evening at Nook Stari Grad, a restaurant recommended by a passerby. The woman waiting on us had recently returned from living in Rochester, New York, and we met another member of the waitstaff who’d been lured back from California. Both were tickled to be home. The Nook’s chicken curry was spicy, the beer was cold, and the open-air seating under an arbor of trees was absolutely delightful. We walked the long way back to the boat, through more narrow stone streets. On the waterfront, there wasn’t a ripple on the harbor, and even in the town center, the quiet was interrupted only by the occasional dog bark.

Wednesday was our free day, and a bura was forecast for the afternoon. After looking at the chart and cruising guide, we decided to sail southeast along the coast of Hvar and across the Pakleni Kanal to the island of Sveti Klement.

We set sail as we left Stari Grad and tacked upwind around the western tip of Hvar. From there, we were able to bear away and reach down the middle of the channel between the two islands. Early on, the 10- to 12-knot breeze was perfect. But as the morning progressed, the wind clocked and turned gusty so that before long, the sea was covered with whitecaps. At the eastern end of Klement, we turned south and sailed through a marked channel that runs close to the island, and then doused sails as we spun to the west to motor a short way up the island’s south coast to Vinogradišće, a small, protected cove that’s home to Laganini Lounge bar & Fish house and a small mooring field just off its dock. After a swim, we headed ashore for lunch at a table overlooking the water, and watched two self-described influencers shoot photos of one another over glasses of bubbly. As we finished our dishes, a motorboat arrived to whisk them away, shooting selfies all the while.

We spent a lazy afternoon swimming off the boat and, before sunset, walked a short distance across Palmižana, where we caught a water taxi to old-town Hvar. The wind was still gusty, and it was a wet ride back across Pakleni Kanal but well worth the trip.

Hvar is a vibrant city, the largest on the island, with a long history of being a trading and cultural center. The city was part of the Venetian empire from the 13th to the 18th century, and a naval base as well, with an imposing fort above the waterfront.

As in the other towns we’d visited so far, we walked. From the harbor, we hiked up a seemingly endless flight of stairs toward the fort. Shops, hotels, restaurants, and residences lined the steps and stone alleyways that led off to either side from occasional landings. We found a small, rock-walled cafe where we ordered a tableful of appetizers rather than a full dinner: sausages, meats and cheeses, octopus, sardines and the like, along with olives, anchovies and grappa. Afterward, we walked some more. A plaque on a monastery we passed dated the stately white-stone building to 1472. In one shop, we spotted a merchant armed with a knife, standing behind a huge slab of prosciutto held upright on an iron stand. You bet we had him carve off slices to take back to the boat, along with a couple of bottles of cherry grappa.

At 2130, with minutes to go before the last water taxi departed for Palmižana, we hustled back down flights of stairs to the waterfront, arriving at the dock with little time to spare. Over the course of the evening, the winds had died, and we had a lovely ride back to Klement, with the night sky ablaze with stars.

Last-Night Raft-Up

After a swim and coffee Thursday morning—and, how could I forget, spinach-and-tomato omelets—we motorsailed east along Klement’s south coast, winding through Soline Bay and the outcrops of rocks at the end of the island. From there, we reached northwest to Šolta and anchored in the bay at Tatinja—called Uvala Tatinja Lonely Paradise on the chart.

Lonely it was. There were only two other boats anchored there and just a couple of houses onshore. In front of us were centuries-old stone terraces built into the hillside and groves of trees; behind us, nothing but the deep-blue Adriatic Sea and a cloudless, deep-blue sky overhead.

That night, we anchored stern-to on a rocky shore in Šešula, with the entire flotilla rafted together in front of a small restaurant. The bay was quite large, and we went exploring by dinghy, motoring alongside new friends Lawrence and Cathy in theirs. In a distant corner, we found a fish farm before turning back. In the afternoon, Sam and Ellie organized inflatable races, with two-person crews paddling their hearts out for bragging rights.

Dinner that night was a group affair, and afterward, the party moved back to the boats, where the monohull crews gladly came to visit our big, roomy cat, helping us clinch Best Party Boat honors at the farewell dinner Friday evening.

The next morning, Josie, Jason and I walked along a coastal trail lined with flowering bushes and the occasional modest house, and came to a small village, Maslinica, where we found a working marina, a couple of shops, a spot serving breakfast, and a 20-foot-long yellow-submarine statue with photos of John, Paul, George and Ringo staring out of porthole-like circles on its side. It was a sleepy tourist town, and a sign near its center said that it had received numerous national tourism awards, including one in 2017 for being the best Authentic Coastal Destination.

On our return that morning to Marina Agana, we had the wind on our nose again, so we took our time motoring toward the mainland. We made a detour to visit the long, deep bay at Vinišće; the shore was built up with houses on one side and an industrial-looking pier on the other. Instead of stopping for lunch, we raised the main and sailed across to the open bay off Trogir, anchoring for a spell to eat and swim.

And then, at last, it was time to return to the marina where we had started. On the dock, once the boat was squared away and before we took a taxi ride into the hills for one last group gathering, I chatted with Bill Truswell, an Irishman in his 70s, who, with his wife and two sons, had enjoyed this week of flotilla-style sailing.

“Stress is something I’m no longer needing in life,” he said.

I couldn’t agree more.