Sea Cat

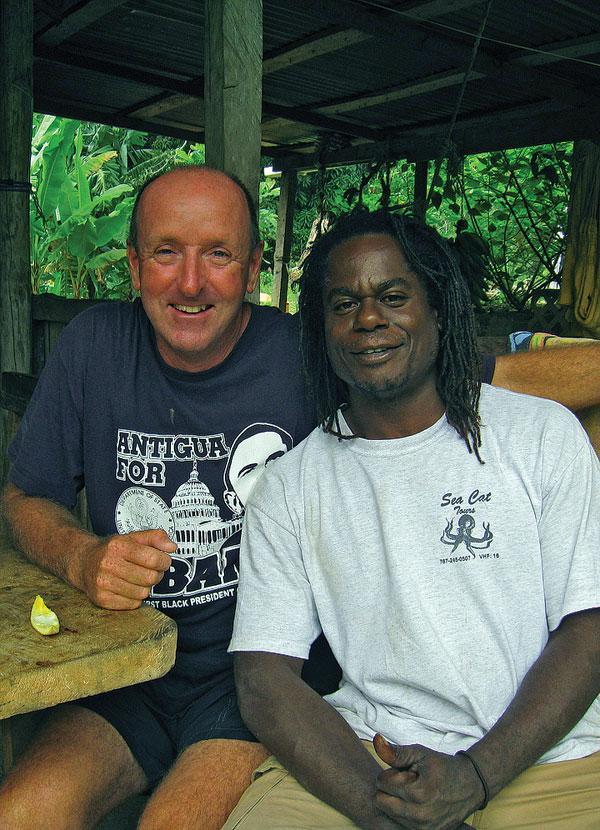

His name is Octavius Lugay, but like other boat boys and yacht helpers who assist sailors with moorings, diesel, ice, and tours on the Caribbean island of Dominica, he goes by a rather dashing nickname: Sea Cat.

Harriet, my wife, and I first met Sea Cat a few years ago when we sailed Hands Across the Sea, our Dolphin 460 catamaran, to Dominica, the most southerly of the Leeward Islands of the West Indies and not to be confused with the Dominican Republic, which is next door to Haiti on the island of Hispaniola, farther to the north. We’d read in a Lonely Planet guide about Dominica, billed as the “Nature Island” of the Caribbean, and we were intrigued. Mountainous and lush Dominica boasts 365 rivers, rain forest and waterfalls, banana groves, mango trees, and exotic tropical plants. Best of all—uncommon in today’s resort-packed eastern Caribbean—Dominica is mostly as undeveloped as when Columbus discovered it for Europeans on his voyage of 1493.

So it was preordained, when we picked up one of Sea Cat’s moorings close to Roseau, the island’s scruffy capital city, that Sea Cat, one of the island’s best guides, would take us on rain-forest treks, up rivers to wild waterfalls, and across the island for pumpkin stew with Moses, a back-to-nature Rastafarian. But it was while driving home to the boat with Sea Cat after the seven-hour hike to Boiling Lake, a 230-foot-diameter flooded fumarole that churns with volcanic gases, like a giant cauldron on the boil, that our real adventure in Dominica began in earnest.

Back in 2007, Harriet and I had sold our home in Massachusetts and launched into full-time cruising, with a twist: We’d established a nonprofit charity organization, Hands Across the Sea Inc., with the intention of lending a hand to local folks wherever we cruised. A nice idea, sure, but how exactly would we help? Harriet, a former schoolteacher, thought that we might be able to assist local schools in some way. The Commonwealth of Dominica, while proudly independent, doesn’t enjoy the influx of money that other Caribbean nations receive from their mother countries. Thus many of Dominica’s schools lack resources.

“Sea Cat, do you know of a school we could do something for?” Harriet asked, as the tires of Sea Cat’s passenger bus squealed on another turn of Dominica’s steep, winding mountain roads.

“Yah, mon! Take you to my school as a young boy,” Sea Cat shouted over the roar of the bus engine, downshifting into the next hairpin. “Could use some help, mon.”

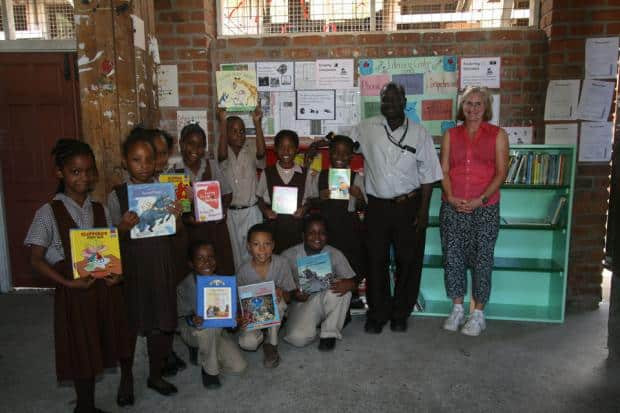

Sea Cat dropped us off at the school, and he was right. Newtown Primary School, perched above a fishing village a quarter of a mile from our moored boat, needed help. The classrooms and student desks were in sad shape, the schoolbooks were sparse and tattered, and the school had no library or sports equipment. Even basic resources, such as pencils, paper, and chalk, were in short supply.

The crew of Hands Across the Sea sailed Caribbean waters to reach the island of Dominica and there help out Newtown Primary School. Photo: Tom Linskey

But the school’s principal was somehow upbeat, the teachers were making do, just, and the kids were like kids everywhere: bright-eyed and bursting with energy and endless questions. We secured a wish-list of items from the principal and promised to stay in touch via email.

We sailed away the next day, heading north up the Leewards and eventually back to the United States to spend the hurricane season in Newport, Rhode Island. Over the summer, we collected gently used children’s reading books and solicited donations for teaching supplies, including French books and an electric school bell. By diving in and doing it, we’d discovered how we could help.

By the fall of 2008, we’d packed and shipped the boxes of books and classroom materials to Dominica. Then we sailed down to the Caribbean and to Dominica again. Securing our lines to the same mooring ball that we’d left six months earlier, Sea Cat looked surprised. “You came back!” he said.

Slowly it dawned on me how we cruisers must appear to locals. Out of the blue we turn up, we see the sights, we drink and eat at the usual watering holes—and then we disappear over the horizon. Since that’s what happens, why would a local person see anything beyond a commercial interest in a visiting cruiser? If someone’s going to leave in a day or three, there’s not much time or reason to try to get to know them.

The author and Octavius Lugay, better known as Sea Cat, take a break from far-ranging adventures across the island. Photo: Tom Linskey

And there’s another thing that seems to come between yachties and locals. Before we reached the West Indies, we’d been hearing a recurring refrain about yachtie/local interaction from other cruisers during cocktail hour chit-chats. One cruiser, in her 60s, seemed to sum it up: “When we come ashore, they just stare at us, and they don’t say a word,” she said of island locals. “It’s like they hate us, because we’re tourists, or because we’re white, or because we have money and they don’t. It makes me uncomfortable. I feel threatened.”

I was prepared to pooh-pooh her, except that we’d felt something similar in the islands. We didn’t feel threatened, exactly, but many times we didn’t feel welcome, either. Fortunately, we’d been reading M. Timothy O’Keefe’s trekking guide, Caribbean Hiking, which explained that West Indian reticence is often interpreted as unfriendliness: “One of the greatest cultural misunderstandings between tourists and locals is who should speak to whom first. Locals like to be spoken to, and islanders expect visitors to be the ones to initiate a conversation, or even to say a passing ‘Hello.'” This seemed a simple key to better cruiser/local relations: break the ice by acknowledging them first. After all, what human doesn’t want to be acknowledged?

We tried this first on the island of Nevis, before we reached Dominica. While rowing our tender to the wharf, Harriet and I saw the usual assortment of locals—fishermen and taxi drivers, the ladies from the concession stand, a few rough-looking young men with Bob Marley T-shirts and wicked-looking dreadlocks—splayed around a picnic table we’d have to walk right by to reach the street. The group stared at us as we tied up to the dock. They stared at us as we unloaded our carry-alls and slipped into our backpacks. They kept staring at us as we walked 200 feet down the pier toward them. Finally, when we were 20 feet away, we smiled and called out, “Good morning, everybody!”

The reaction was electric. “Morning, morning!” “O.K.!!” “Yah, mon!” “Good day to you!” “Welcome to Nevis!” Everyone in the group, even the assumed-to-be-surly young guys, wore a smile. We’d just triggered our first West Indian shout-out, and it would turn out to be the first of many. We were still sailors, still tourists, still only visitors to their island. But now we weren’t strangers.

We wound up staying for 11 weeks on Dominica—far, far longer than we’ve remained in any spot in our 20 years of cruising. Welcomed and encouraged by Jerry Coipel, the principal of Newtown Primary, and Solange Payne, the French teacher, we tackled various jobs. With help from the Roseau chapter of the Lions Club, we retrieved our shipment from customs. We bought lumber and glue and, with help from other cruisers, built and painted a dozen bookshelves. Harriet read books to students and taught classes as a substitute teacher.

I spent so many days crisscrossing Roseau searching for wall brackets, paint rollers, and drywall screws that I eventually knew not only the local merchants but also the town’s collection of wandering souls, from the barefoot, homeless man who looked like Jesus to the old Rastafarian with a cane. And they knew me. We said, “Morning, morning!” or “Good afternoon.” We passed each other with a nod and a smile.

Meanwhile, Harriet was networking, talking to people and uncovering new projects for Hands: a 650-student primary school that needed a playground and “books for boys”; a literacy center for teachers that needed support; a kindergarten that needed just about everything. Her circle was growing—not only growing, but encircling us.

One day a Newtown Primary student, about 8 years old, brought me to a halt on the street in front of the fishermen’s cooperative. “Where is your wife?” the little boy demanded, a fresh baguette under his arm and a book bag on his back. He was still in his school uniform, but his pants were after-school rumpled, one shoe was untied, and his shirt was untucked.

“I’m, uh, not quite sure where she is,” I said, looking around for Harriet.

We’d been walking together, but suddenly she was gone. Had she crossed the street to talk to one of the teachers? I had no idea.

“I think she went thataway,” I said, pointing astern.

“O.K., den,” the boy said.

I got it. On Dominica, the web of community is strong, and it’s not long before your business becomes everybody’s business. It felt nice to be included—as long as I could find my wife again. The longer we stayed on Dominica, the more we understood how things worked.

Island life can be puzzling. Why so many crumbling buildings and homes? Why the ever-present group of people who don’t seem to work? Why is the pace of life so slow that the days are long and lazy, yet slip away with surprising speed?

Stay awhile and you realize that lack of funds means you make do with what you have, and an unemployment rate of more than 30 percent means that a lot of people don’t have work to do. As for the slow pace, it does seem to keep everything in perspective. There’s less agonizing about making money, and there’s more time spent chilling with family and friends. But that doesn’t mean island life is free of stress.

Sea Cat, for example, a seemingly laid-back island guide, puts in long days and works six days a week. His wife works full-time, too, and every weekday morning at 0700 their three young daughters are marched out the front door in school uniforms, starched and spotless.

And we noticed that people on Dominica fall in and out of love, get married and divorced, shop for Christmas presents, give their kids Sweet 16 parties, get in car accidents and go to church, catch colds and come down with the flu, run perpetually late, and make the same New Year’s resolutions every year. It’s all a lot like back home.

Eventually—following Carnival, a dinner at a resident professor’s home, and a locally written, produced, and acted play at the downtown theater (including school principal Jerry Coipel playing against type as “Rock,” a bad guy)—we moved on from Dominica. On our last island tour/trek with Sea Cat, during the 30-minute drive across the island to the trailhead, Sea Cat waved, honked at, smiled at, fist bumped, or shouted “Yah, mon!” or “O.K.!!” to practically every single person along the way. Each time, he received a grin, a wave, a shout.

Flabbergasted, I said to him, “Sea Cat, do you know everyone on Dominica?”

He grinned. Harriet and I had made some progress, but we were still catching on to how things work in the West Indies. “No, mon. Sea Cat don’ know everybody. But everybody know Sea Cat.”

And now you know him, too.

Tom and Harriet Linskey spend their winters in the eastern Caribbean assisting local schools. Since 2007 their non-profit organization, Hands Across the Sea, has shipped over 102,000 books to 178 schools, libraries, reading programs, and youth centers.

For More Dominica Info

Discover Dominica: The Nature Island: www.dominica.dm

Hands Across the Sea Inc.: www.handsacrossthesea.net

Nature Island Destinations: www.natureisland.com

Sea Cat’s e-mail: seacat55@hotmail.com

A Virtual Dominica: www.avirtualdominica.com