The Hawaiian Islands are one of the most remote places on Earth. Nearly in the middle of the North Pacific, more than 2,000 miles from the closest continent and nearly 1,000 miles from the nearest island group, Hawaii is truly a long sail from anywhere. Yet, because of its strategic location as the only viable stopping point for voyagers transiting the vast North Pacific, sailors have visited here for centuries. It’s not uncommon to find vessels from all over the world berthed in one of the few marinas, awaiting departure for distant new horizons. But while lots of cruisers come and go each year, my fiancée, Gayle Suhich, and I wondered why we so seldom heard of people spending any time actually cruising around this large archipelago.

Without question the most popular destination for long-distance sailors is Honolulu, on the island of Oahu. Most vessels under 80 feet put in to the Ala Wai Yacht Harbor, located right next to the world-famous tourist destination of Waikiki Beach. Within this harbor is a state-run marina with nearly 700 slips and two yacht clubs, the most notable of which is the Hawaii Yacht Club, where we kept our boat. Founded in 1901, the HYC maintains a dock they refer to as the “Aloha Dock.” Aloha in its simplest translation means “welcome,” and this long face pier designated for transient sailors is often filled with as many as a dozen vessels from all over the world. Yet, when we’ve spoken to these cruisers, few say they’ve stopped at any other Hawaiian port. To learn why, we set out from Honolulu in late September 2013 to explore. Before we did, we asked a few of the more experienced local sailors for their best picks for anchorages and tactics for crossing the sometimes boisterous channels between islands. We were generally surprised at the unfavorable comments we got concerning cruising conditions. We heard lots of advice, which mostly centered around ways to avoid getting beaten up too badly between the islands and ways to avoid anchorages with too much surge.

The most useful advice, it turns out, was to wait for a lull in the sometimes strong trades that affect these islands. We were advised to wait for light to moderate trade-wind conditions before setting out, and to make our upwind channel crossings at night when the winds tend to lie down a bit.

Despite optimistic forecasts on NOAA weather radio and PassageWeather.com, we found that the local conditions between the islands can be startlingly different from the forecast or the buoy reports from far offshore. Wind acceleration between the high mountains is the main reason for this, and the heating up and cooling off of the large landmasses of these mammoth islands also markedly impacts weather in the channels.

Coming from the Caribbean, we may at first have taken the local warnings with a grain of salt. We thought, “How much worse than the Anegada Passage or the Mona Passage or Kick’em Jenny can it possibly be?” Turns out, a lot.

Our first passage to windward across the Kaiwi channel between Oahu and Lanai (see map on page 40) proved to be 15 hours of hard bashing in 30 knots. Solid waves often washed the foredeck. Our 50-foot Flying Dutchman, Small World II, struggled valiantly through this and shook off each onslaught with barely a shudder, but we imagined what it might be like on a smaller vessel: Not fun! With swells and wave trains coming from three directions and piling up from deep water onto the relatively shallow Penguin Banks halfway across the passage, it was surprisingly rough, but in the lee of Lanai, things smoothed out.

Lanai is a strange-looking dome-shaped island that’s cultivated mostly as a pineapple plantation, though in general it’s fairly arid. Stark, craggy cliffs 500 feet high in places abut the sea on the leeward coast, with only a few small indentations that might offer a limited bit of protection as anchorages in calm conditions. When we were there, the southerly swell made these places untenable. Carrying on to the island of Maui was more attractive, and we found a spot right off the old whaling port of Lahaina by early afternoon on day two.

Once a small fishing village, Lahaina ultimately became the Hawaiian capitol from 1820 to 1845 under the rule of King Kamehameha. Because of its location on a somewhat protected part of the leeward coast in the wind shadow of a substantial range of 5,000-foot mountains, abundant fresh water nearby and a benign climate, it became a favorite port of call in the days of working sail. Although the anchorage is an open roadstead, there’s a long shelf with decent depths and good holding. Its location on a gentle bulge in the coast offered cumbersome square-riggers the ability to sail in or out, no matter what the wind direction. By the mid 1800s Lahaina had become the roughest and most infamous port of call in the Pacific. At any one time, 50 or more whaling ships might be at anchor, and the fights and carousing of sailors ashore were legendary.

Today, although the town is a touristy shadow of its glory days, with knickknack shops and eateries crammed along the waterfront, it still maintains an enjoyable laid-back atmosphere.

The Lahaina Yacht Club is a welcoming haven for sailors. Overlooking the anchorage, the club is entered through a swinging saloon-style doorway. This historic landmark became a favorite hangout for our crew while ashore, offering solace and cool beverages amid walls crammed with old photos, trophies from early and current sailing events and historical references dating back almost two centuries.

Friends who were living ashore took us on an island tour that included horseback riding and a pre-dawn expedition to the volcano summit of Haleakala, which at over 10,000 feet had us shivering in the below-freezing temperatures but gave us a breathtaking view of the sunrise over the island of Hawaii, 50 miles away.

After a few more days of sightseeing and land exploring, we were ready to move on. We canned the idea of heading farther upwind to the Big Island of Hawaii because of the persistent south swell, which would have made all the leeward anchorages very uncomfortable, and also because the winds were refusing to lessen. The Alenuihaha Channel between Maui’s 10,000-foot peak and Hawaii’s 13,000-foot peaks is the worst stretch of water in the whole island group, and crossing farther to the east would have meant beating into 35 to 40-plus knots and short, confused seas. If there had been a great anchorage on the other side of the channel, we would’ve been tempted to go for it, but with the promise of days on end of rolling heavily while at anchor off a sparsely inhabited coast and with no ground transport readily available, we decided instead to head for the south coast of Molokai, 25 miles to leeward.

We had heard that Molokai is the least touristy of any of the main Hawaiian islands. From what we had learned, there was a very good anchorage in the lee of a small commercial wharf about halfway down the south coast, within a pocket in the reef that offered room for several boats. If we were to arrive to find the anchorage full, we’d be forced to beat upwind back to Maui or head farther down the coast to a less desirable anchorage we had seen on the charts. As luck was to have it, we found a perfect spot to anchor in 10 feet of thick mud a short dinghy ride from the main commercial wharf.

The sail over was an incredibly beautiful fast reach out of the lee of Maui. I had put only a single reef in the main, anticipating no more than 20 or so knots of wind because the NOAA forecast had predicted only 15 knots in the channels. Within a quarter of a mile we sailed from 10 knots of wind into 28 knots and then 33 knots, which slammed us over and cranked us up for one of the best sails we’d had in a while. Although a bit overpowered, we decided not to reef further because the passage is only about 15 miles across. Small World II consistently sailed at nearly 10 knots along the crests of waves. Within a short time we were off the sea buoy to the anchorage at Kaunakakai, and by noon we were motoring ashore in our dinghy.

While most of the other Hawaiian Islands are now predominantly inhabited by non-Hawaiians, Molokai is still largely populated with native Hawaiians, many of whom are descendants of the original settlers who came in the first millennium. It was refreshing to be in a place not geared to tourists and that had not changed significantly in decades.

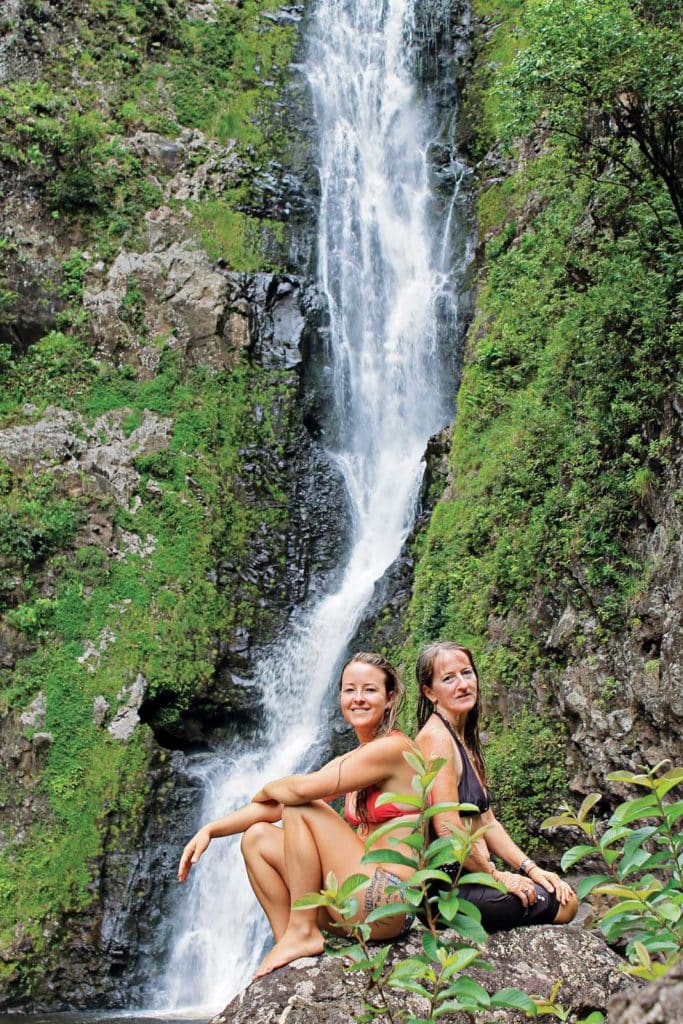

The most beautiful beaches on Molokai are along the western coast, and for the most part they were deserted. Several hiking trails offered a chance to see a bit of the Hawaiian lifestyle of yesteryear, and we managed to find a guide who took part of our crew up to a waterfall and through farmlands that had been cultivated for nearly 1,400 years. At the head of the Halawa Valley, Hawaii’s tallest waterfall feeds a beautiful, clean river that helped make this valley an ideal place for human settlement. Archaeologists have carbon-dated the earliest evidence of humans here to approximately AD 650. Our guide agreed to take us to the valley only if we showed an earnest desire to learn about the culture and respected the residents’ way of life. A visit to this sacred place meant we were there as guests on their terms; they were not there as servants to ours. It was awe inspiring and a highlight of our voyage.

Just beyond this valley lies the northern coast of Molokai. It has the tallest sea cliffs in the entire island chain, plunging nearly 4,000 feet from cloud-enshrouded, verdant peaks to the pounding, rugged, boulder-strewn surf line.

Winding back along the one-lane road toward the more populated middle section of the island brought us eventually to the only road that leads close to, but doesn’t reach the large Kalaupapa Peninsula, which juts out from the north coast. A leper colony was established there in 1866, and descendants of the banished remain today. Their only access to the outside world is either by a daily in-and-out charter flight or by mule down a hair-raising set of switchbacks.

If the weather is settled, you can anchor off the peninsula, which is now a national historical park. One day we hope to sail back and visit this place of sorrow, suffering and triumph of the human spirit.

Finally sated with the local culture, we made a pre-dawn departure for the 50-mile broad reach back to Oahu. Winds were forecast to be 20 to 25 knots, and this time, with a double reef and a bright blue sky, we screamed across the Kaiwi channel at 8.5 knots and under control the whole way. Just as we were nearing the southeast coast, Gayle caught a small yellowfin tuna, which felt like a nice gift to top off a wonderful 10 days of sailing and exploring in one of the most awe-inspiring island groups on our small world.

Bringing our boat back to her berth at the Hawaii Yacht Club, we knew that as soon as we could get away again, we would continue to explore this very special island group. Big challenges, bold landscapes and grand adventure await anyone who is willing to spend the effort to sail through the islands where Capt. Cook, George Vancouver and countless small-boat voyagers have visited. The real Hawaii is still out here awaiting discovery.

Resources

If you’re planning to include the Hawaiian Islands while cruising the Pacific, here are the guides and charts that the author found useful:

• Charlie’s Charts of the Hawaiian Islands, 4th edition, by Charles and Margo Wood. $22.50; www.charliescharts.com

• Cruising Guide to the Hawaiian Islands by Carolyn and Bob Mehaffy. $30; 2006; Paradise Cay Publications; www.paracay.com

• Landfalls of Paradise: Cruising Guide to the Pacific Islands, 5th edition, by Earl R. Hinz and Jim Howard. $47; 2006; University of Hawaii Press; www.uhpress.com

This article first appeared in the May 2014 issue of Cruising World. Todd Duff and Gayle Suhich have been cruising and living aboard since the 1980s and have sailed to 22 countries. They are currently cruising in the Pacific aboard their Flying Dutchman 50, Small World II.

Lahaina, Maui

coast of Lanai

Small World II sails out of Honolulu

Hawaiian Islands cruise

Hawaii’s tallest waterfall

Molokai

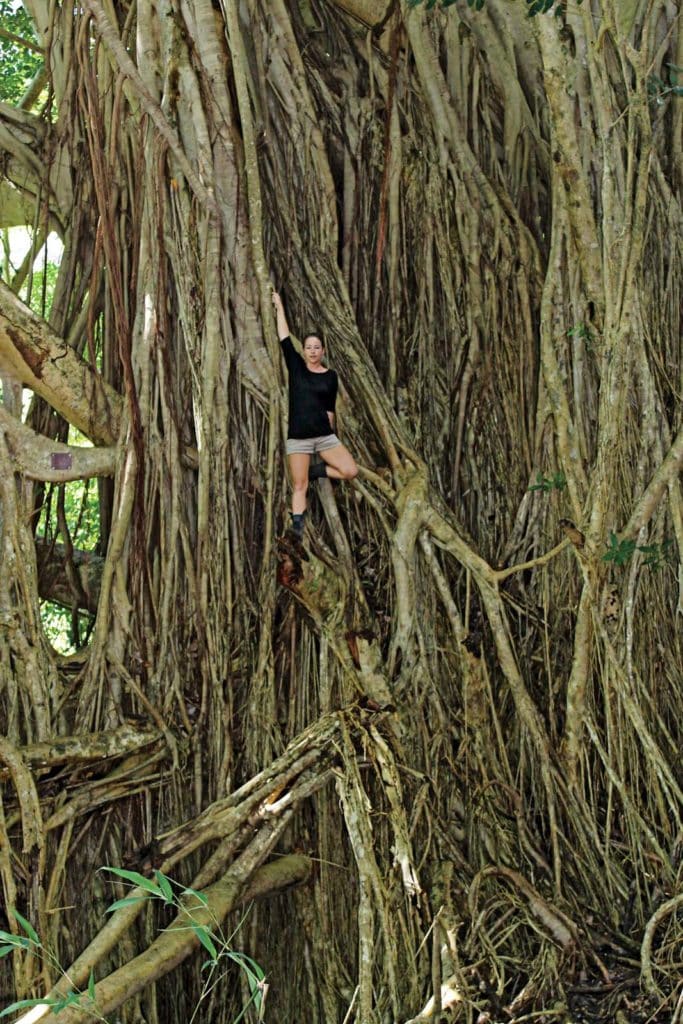

banyan trees

Molokai Family

Maui landfall at Lahaina

Paddlers at sunset

Landfall on Molokai

Sarah Suhich at the Sacred Waterfall on Molokai

Maui and Lanai