HallIndoSt

Whoever said “Getting there is half the fun” certainly wasn’t traveling on this boat. Not that “getting there” doesn’t have its moments, but “being there” undoubtedly accounts for far more than just half the fun. One reason for this lopsided division of pleasure could be that Hoku Pa’a, my overloaded Ericson 30, doesn’t exactly make for jet-lag-inducing passages. But that added payload of toys-five surfboards, four fishing rods, three guitars, two paragliders, two full sets of scuba gear (plus air compressor), and one windsurfer-pays off when the anchor drops. That’s when the good times begin to roll.

Admittedly, my version of fun is a little extreme. In Indonesia, the local villagers came to call me “Crazy Bird,” and my family-who’ve fielded their share of calls from emergency rooms-would probably agree. It was my recently acquired interest in paragliding from the tops of active volcanoes, along with a passion for surfing, that drew me to the 3,000-mile-long chain of islands that make up Indonesia. The archipelago forms the eastern fringe of the ring of fire, the chain of volcanoes that circles the Pacific Rim. A locale where the Indian Ocean swells collide with still-smoldering islands, Indonesia seemed hands down the place to be.

Ostensibly a photographic odyssey, the trip’s true purpose was to pack as many new thrills as we could into five months. We planned to head south with the northeast trades from Guam, where I was working at the time, and make a beeline to the big waves on the south coast of the Indonesian archipelago. We’d then surf, sail, and paraglide our way westward to Bali, where we’d fly off Gunung Agung, the island’s highest volcano. After surfing the famous breaks of Panaitan island, west of Java, we’d cap off the journey with a flight off the top of Anak Krakatau, the active volcano that has risen from the remnants of its predecessor, Krakatau, which exploded with the force of a 200-megaton bomb in the late 19th century.

The only problem was that shortly before the voyage was to start, the “we” was still just an “I.” But I’d never had trouble filling positions before, so I didn’t worry. Predictably, a surfing buddy from Hawaii signed up to fill the spot. When Skip Wunderlich met me in Guam, his six surfboards brought our total to 11 (not counting the sailboard), and any maneuvering on deck was best left to Olympic gymnasts. With a roller-furling jib and all lines leading to the cockpit, this obstacle course would only interfere with setting the spinnaker. Unfortunately, we were never so challenged. Our late start and an early southwesterly monsoon meant the wind only accompanied squalls-which came often-and it was always dead on the nose.

It didn’t take long for Skip (who’d ignored my advice to load up on Scopolamine) to curse the joys of sailing. I assured him that the passage south would get better, but day after day of headwinds and rain had me wondering when the rainbow would appear. Eventually, we slogged our way 1,000 wet, windward miles to our first Indonesian landfall.

Jimmy Hall|

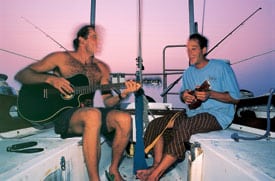

|I see no Grammies in our future, but Skip’s mean ukulele adds respectability to our sunset jam at Sumba, the island where we struck gold.|

Buzzed in Irian Jaya

In search of more cooperative winds far off our intended track, we motored along the northern coast of Irian Jaya-the western, Indonesian half of New Guinea. The scene was irresistible: jungle-clad mountains rising abruptly from the narrow beach, straight up into the clouds. Moments after we decided to take a quick look, the anchor dropped and we were rowing ashore. On solid ground again, we danced around chanting “We’re on Irian Jaya! We’re on Irian Jaya!” Barely seconds later our dance became more animated, and the verse changed to “We’re being eaten alive by millions of invisible insects!” Our stay was rather brief.

Putting off further adventure in Irian Jaya, we laboriously worked our way south. Finally, many degrees south of the equator-and far south of where we’d expected to find favorable winds-the breeze began to swing to the east. Sailing became tolerable. The wind swung a little more and it became nice. We were speeding along, plunging deeper into Indonesia by the hour. Skip shook off his seasickness and shipboard morale soared.

Looking at the exotic names on the chart, I realized that these “Spice Islands” could occupy us indefinitely, but an advancing surf season kept us rushing through the Ceram and Banda seas. After a quick check in at Ambon, the historic port in the Moluccas, we continued south. Soon, we had not only the wind behind us but the current as well.

As seasonal winds push water from the South China Sea, the Pacific Ocean, and the Indian Ocean through the Indonesian archipelago, swift currents funnel through the straits between islands. The currents are predominately southerly during the trade-wind months, June through September, but they can change direction unpredictably. They’re often fierce, creating whirlpools and breaking waves in deep water. Although we were spared the whirlpools, we met our share of overfalls, and within several months, we became quite adept at moving backward under a full press of sail.

As we motored in the lee of smaller islands north of Timor, our speed jumped impressively. Even with the engine ticking slightly above idle, we still smoked along at nearly eight knots. The strong current often whipped the sea into a chaotic mess, but our amazing speed made up for the violent ride. As we neared the end of our hurried rush south, Skip finally believed that his digestive drama was over for good. Even the random bashing that the current delivered failed to bring a relapse of his seasickness.

Mr. Jimmy, Crazy Bird

The small island of Roti, west of Timor, marked the true starting gate to our Indonesian excursion. From this point, we were upwind of one of the most surf-riddled island chains in the world. By sticking to the exposed southern coasts, we not only found excellent surf; outside of Bali, we saw only four other cruising sailboats in five months, and this was during peak cruising season.

Jimmy Hall| |Powered by “long-tail” diesel engines, a local ferry hugs the Bali coast. With our 11 surfboards strapped to the deck, Skip and I run toward the next perfect spot.| Roti immediately provided a taste of the great waves for which Indonesia is famous, and we were soon hopping westward through the Lesser Sunda Islands. Our first big find came on the southern coast of Sumba. After sailing into a nearly deserted bay, we anchored in an ideal setting. Bleached sand lined the bay, a perfect right-hander peeled off the point, and steep cliffs bordered the anchorage. No other boats were around, and the nearest village lay well inland, so we had it mostly to ourselves.

The weather dictated the daily activities. In the mornings, when the wind blew off the land, we surfed big, powerful waves. In the afternoon, when the sea breeze picked up and spoiled the surf-that was the time for paragliding.

A corny but accurate description of paragliding is man’s greatest dream in a backpack. Often confused with hang gliding, skydiving, or parasailing, paragliding is a mixture of all three. Similar in appearance to a parachute, the paraglider works on the same principles as a hang glider. You find a cliff or steep slope, let the wind lift your wing, and step off over the edge. The paraglider is the simplest, easiest, least expensive way to achieve sustained flight. It’s also the only aircraft that will fit in my boat.

During the first few days, I found and cleared a take-off site atop the steep cliffs, where the onshore wind had nowhere to go but up. After launching into this rising air, I could soar for hours, reaching an altitude of nearly 1,000 feet. On the day of my first flight, every person in the village gathered on the beach to watch. Astonished, they soon began calling me “Mr. Jimmy, Burung Gila.” Crazy Bird. Whenever I visited the village, everyone I met-wrinkled grandmothers to tiny kids-would invariably ask, “Kapan terbang?” “When fly?” They never tired of the “man with the umbrella for flying.”

We enjoyed this place so much that we stayed three weeks before reluctantly heading west. After finding more surf along the southern coast of Sumba, we stopped at the western end of the island to visit the traditional villages of Wainyapu and Ratenggaro. The tall conical roofs of the thatch houses in these kampung stood above the surrounding treetops like pointed haystacks. The homes were decorated with boar tusks and water buffalo skulls. Stone kateda in the village and surrounding fields marked sacred spots dedicated to protective marapu, the spiritual forces of gods, ancestors, and spirits that form the basis of traditional Sumbanese religion. Larger monoliths marked graves of honored ancestors.

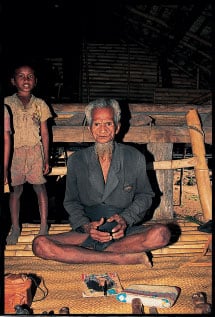

Jimmy Hall| |The chief of Ratenggaro, Sumba, welcomes us to his village.| By dinghy, we explored for several miles the river that flowed between the two villages. Although both villages on the coast see occasional foreigners, it was clear that the children at the inland villages regarded us as alien creatures. Near the coast, the children ran to follow us along the river bank. Deeper in the jungle, they fled in fear.

Bali High

Almost two months had passed since we first stepped ashore in Irian Jaya, and as we sailed westward through the islands, memories of the dreary passage south soon faded. Winter in this part of Indonesia is ideal. Rain is extremely rare, and the southeast trades blow predictably from April through October. Surf, of course, took first priority, but when the waves weren’t up, we had no trouble keeping ourselves amused as we stopped along the long south coast of Sumbawa.

Calm days meant fishing or diving; windy days demanded windsurfing; light winds and the right landscape were for paragliding. Gaps in between were filled by hiking, exploring rivers, visiting villages, and taking care of the inevitable boat work. Our anchorages were as varied as our days. Some were calm, others rolly. Most were lonely. Sometimes we stayed a day, sometimes 20 days. Even a broken boom, caused by an accidental jibe shortly before reaching Bali, couldn’t spoil the fun.

Bali stood in stark contrast to the Indonesia we’d known during the previous two months, but we welcomed the change of pace. After a long stint of roughing it, we were due for a little taste of civilization-if Bali’s surreal interface of 1,000-year-old traditions and full-scale tourism can be called that. With a little effort, we found room to anchor in the crowded Bali International Marina at Benoa. A big cruising rally was arriving, and boats poured in daily. At one point, 65 cruising sailboats filled the marina and small anchorage. Clearing in with the officials required visits to five different offices, but other than consuming an entire day, it wasn’t a problem. With this out of the way, we wasted no time in our new quest to consume large quantities of cold Bintang beer and nasi çampur, a delicious, although unpredictable, dish of rice mixed with whatever meat and vegetables the cook has at hand.

Slightly larger than Rhode Island and home to about 3 million people, Bali gets bombarded by about half that number of tourists each year. Still, traditional Balinese culture manages to thrive. Religion, a unique form of Hinduism, dominates everyday life. Temples outnumber homes, and the Balinese constantly make offerings of incense, food, and rice to the gods. The island’s terraced rice fields, descending to the sea like a green-velvet staircase, make for a stunning landscape.

Bali is famous for surf, and we had some good days at such legendary breaks as Uluwatu, Padang Padang, and Impossibles. Bali is also known for its nightlife, and long nights in the energetic beach town of Kuta can certainly render one useless for the following day (as Skip discovered after a rare Bintang binge).

For me, the highlight of our stay in Bali was Gunung Agung, the often cloud-wreathed volcano in the northeast part of the island, far from bustling Kuta and the crowded capital, Denpasar. Gunung Agung is Bali’s holiest mountain, locally revered as the dwelling place of gods. To reach the 9,842-foot summit required a grueling, five-and-a-half-hour climb that began at 1 a.m. under a full moon. The sunrise and view from the top were spectacular, but the biggest reward was the descent, which I made by paraglider. The bumpy air offered little opportunity to soar, but the vista of the fertile rice paddies below left me with little doubt why the Balinese so revered the mountain. I landed among boulders spewed during Agung’s 1963 eruption, which ominously came in the midst of Bali’s greatest religious ceremony, Eka Desa Rudra, a rite of purification performed only once every 100 years.

Above Krakatau’s Caldera

With the end of surf season approaching, we set off with our fortified boom and were soon on our own again, sailing along the 700-mile southern coast of Java. This often boisterous stretch of water treated us well, and we had a benign trip. Despite Java’s reputation for good surf, we made few stops along the coast. We had set our sights on Panaitan island, in Selat Sunda (the Sunda Strait), between western Java and Sumatra.

Panaitan’s best surf spot competes for the title of the most perfect wave in Indonesia. Since the waves break nearly on top of an exposed and notoriously sharp reef, the wave is also one of the most dangerous. The island is an uninhabited wildlife reserve, part of West Java’s Ujung Kulon National Park, home of the few remaining wild Javan rhinos. Panaitan’s remoteness and the intensity of its surf keep the visitors to a minimum. During our stay, we saw only fishermen.

We held our vigil in Panaitan’s big bay for 22 days, and we were rewarded with only two days of surf. Fortunately, the waves were as perfect as we’d heard: Record tube rides were possible on every wave. The only thing that could have made the surf any better would have been a more reasonable safety margin. On the second day, Skip met the reef in a violent way, and the resultant reef rash ended his surfing. He was definitely filling the role of the fall guy on this trip.

After three weeks of Panaitan’s wilderness, we came to the painful conclusion that surf season was over and the island’s perfect point wouldn’t come alive again until the following winter. Consolation came in our next destination, only 40 miles away, the “child” of Krakatau.

Once a landmark for sailors navigating the Sunda Strait, Krakatau volcano exists only in ship’s logs, charts, and other records from the time before it shook the Earth. In 1883, Krakatau erupted with such force that the blasts were heard for thousands of miles. In Jakarta, 100 miles from Krakatau, windows shattered and noon became as dark as midnight. The ejected ash circled the globe for weeks, falling on ships 4,000 miles away. In the Philippines and Australia, the eruptions were reported to sound like the discharge of heavy artillery. The estimated 11 cubic miles of ash, pumice, and other material spewed into the atmosphere was so voluminous that it altered the world’s climate for years. The colossal eruptions destroyed over 160 villages and killed 36,000 people. Tsunamis caused most of the deaths, engulfing nearby shores and influencing tidal differences in places as far away as the English Channel.

During the eruption, the original volcano shattered. Krakatau is now composed of several islands, some new islands, some part of the original Krakatau. From the center of these islands rises the volcano Anak Krakatau, or Child of Krakatau. Since emerging above sea level in 1926, Anak Krakatau has grown to a 400-foot peak, ranking it among the world’s newest islands.

After anchoring at the base of the smoking mountain, we quickly hit the beach and started climbing. The arduous hike consisted of scrambling up loose scree, often sliding back as much we went up. Near the top, we passed odorous steam vents; the sulfurous gas burned our eyes, noses, and lungs. From the narrow ridge of the summit, the volcano sloped steeply away on one side and fell vertically into the crater on the other. The edge of the smoking crater provided an excellent vantage point overlooking both the volcano and the surrounding islands, but I didn’t linger to enjoy the sights.

Jimmy Hall| |I soar over the steaming crater of Anak Krakatau. The volcano’s steep and rocky terrain (below) made for tricky takeoffs and landings.| With a steady breeze blowing up the volcano’s slopes, conditions were perfect for paragliding, so I wasted no time launching. Soaring along the volcano’s windward face, I gained altitude with every pass and was soon gliding more than 150 feet above the mountain. The view from high above was spectacular, but the biggest thrill came from low-level flying, skimming just above the crater’s rim with my feet enveloped in the smoke and steam.

After logging nearly 10 hours of flight time and inhaling our fill of volcanic dirt, we moved four days later to nearby Rakata Island for diving. The underwater terrain near the volcano is, understandably, rather bleak, but the surrounding waters are full of life. I dove four times a day, shooting one roll of film per dive, and I never lacked for subjects. During one dive, my heart nearly stopped when a concussive shock reverberated through the water. I quickly ascended, certain that the volcano was now erupting-this was a photo opportunity I didn’t want to miss.

To my disappointment, Anak Krakatau looked no different. I returned to the moray eel I’d been shooting to find that the tremor had sent uncomfortably cold water up from the depths. I tolerated it until condensation formed on the port of my camera housing, forcing me to rise to warmer temperature.

Jolted in Jakarta

Leaving Krakatau four days later, we found ourselves battling a strong southerly set in the Sunda Strait. During our first 12 hours, we made less than 30 miles. Trying to escape the current, we hugged the west coast of Java. All night we motored close to shore in the lights of the oil refineries, power plants, commercial docks, and other massive industrial complexes that line the coast. Early the next afternoon, we sailed into the sprawl of Jakarta, Indonesia’s biggest city. We pulled into the Marina Ançol, an expensive but safe refuge. Checking in was simple, as we had to see only the marina’s harbormaster. Jakarta wasn’t listed on our cruising permit, but a small donation straightened things out.

Our arrival in Jakarta made sailing into Bali seem like a gradual re-entry to the world of men and machines. For the past month, we’d been among wild monkeys and a smoke-belching volcano; now, after just an overnight sail, we found ourselves swallowed by Jakarta’s pollution, traffic, and 9 million people. This chaotic metropolis, although not a highlight of our Indonesian experience, still left an unforgettable impression.

Jakarta marked the end of Skip’s stay on Hoku Pa’a. His wounds from Panaitan were healing well, but despite all of the great surf we’d found, it seemed doubtful he’d volunteer for another adventure involving a boat.

After taking on fuel, water, and provisions and making a quick plane trip to Singapore to renew my expiring visa, I set off singlehanded for Bali. The 600-mile sail though the Java Sea from Jakarta to Bali was challenging work. Oil rigs, fishing stakes, shipping traffic, floating debris, and countless fishing boats required that I keep a diligent watch. Many of the obstacles were unlit, but the full moon illuminated most of the long nights and made spotting these hazards easier. Every other night, I anchored along the Java coast to sleep. Ten days later, fairly exhausted, I

sailed into Bali, completing a 1,500-mile circumnavigation of Java and Bali.

Benoa’s calm harbor and the prospect of a long stay brought a sense of relief, although I knew I’d grow restless soon. I planned to base myself in Bali, do some much-needed work on the boat, then pore over the charts again. Even after five months in Indonesia, we’d just seen a tiny fraction of the country. For the moment, though, I had only a vague idea where I’d go next, and no idea who’d come along-but then that’s also part of the fun.