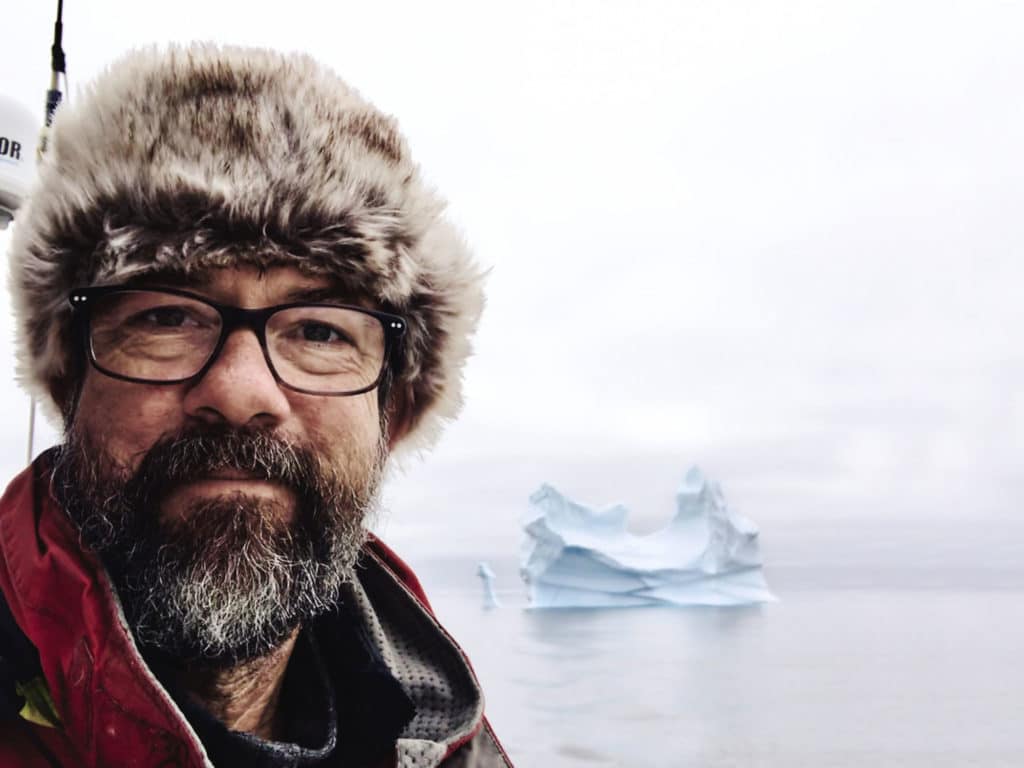

August 15, 2019, Graham Harbor,

Devon Island

Day 261 of the figure 8 voyage

Compared with that roaring river, the Southern Ocean, the north is a cathedral of quiet. From Mo’s remote Arctic anchorage at Graham Harbor (74 degrees N, 88 degrees W), there was such stillness that I could hear my ears ring and the low grumbling of a nearby growler as it jostled the rocky shore. Here, in late summer and yet at the beginning of the Northwest Passage, I would gnaw my fear for an evening while awaiting another discouraging ice report. The coming days would decide the success not just of this transit, but of the entire Figure 8 Voyage as well. Three years of preparation and two yearlong attempts would all ride on a few hundred miles of icy water, and the going did not look good.

Often during Mo’s southern circuit, I anticipated with pleasure the anticlimax to follow our second Cape Horn rounding. There, at 56 south, we would be released from the imperative to make easting; we would climb into the hospitable Atlantic, into the unfaltering and floral trades requiring no hand on sheet or tiller, or overnight calls to reef. These would be fit refreshment, I thought, after our arduous time in the wilds down below.

And what we got on the advance toward Recife, Brazil, was warmth aplenty, but also a season surprisingly devoid of steady breezes and a sea clogged with sargasso weed. Where the south had promised—and usually delivered—a gale a week, now we were made to endure as many calms. By the time Mo drew level with Bermuda, we found it difficult to run off even 100 miles from one sweltering noon to the next. Ever so slowly, the lengthy blue ribbon of Atlantic slipped by. Then, on May 31, 2019, the port of Halifax emerged from fog, and here we made our first stop on Day 237 out of San Francisco.

This port call too contained its surprises. For one, as I handed Mo’s lines to Wayne Blundell, dockmaster of the Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron, the man handed back an envelope full of cash—an entry custom I’ve not found typical of foreign ports. “Sent ahead by your friends,” he said, “so you can buy a round at the bar.”

In Halifax we refitted over the course of a month. Items not even contemplated in the previous 31,000 sea miles—anchors, chain and windlass, autopilot, depth sounder, dinghy and outboard, the radar, the little red engine—were serviced, run hard, tested and tested again for the coming Arctic trial. And all the while the Canadian ice charts declared only pas d’analyse, nothing to report. Summer solstice had come and gone, and the ice remained unmoved.

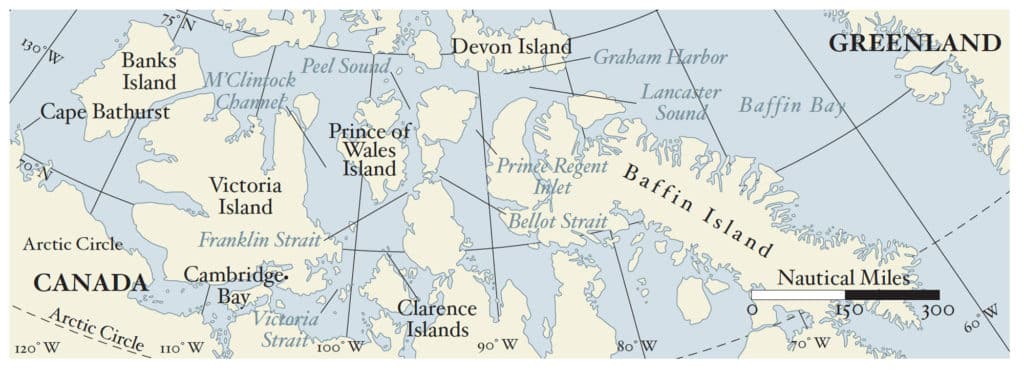

Mo and I departed Halifax for the north on July 2 for an uneventful run to St. John’s, Newfoundland, and then began a slow jog up the west coast of Greenland, more for the pleasure of it than to avoid the famous middle pack. There was no hurry. By July 15, reports showed that ice in Lancaster Sound had begun to flush, but it hadn’t shifted at all in Peel Sound or Prince Regent Inlet.

In Nuuk, and with the help of local magistrate Jens Kjeldsen, I bought a rifle for defense against the polar bear. The attendant took my cash and handed over the firearm and shells with as much concern as if I were buying a quart of milk. Then I followed Kjeldsen to a birthday party for his Inuit wife. These two had just returned from a circumnavigation via the Northwest Passage. “My wife is the only Inuit to have sailed around the world,” Kjeldsen said. “She made all the newspapers.”

Below Disko Island, icebergs appeared. Distant white specks jutting above the blue plane grew to gothic spires or became tabular and sheer, all calved brash that flowed away on the current like the tail of a comet. On July 26, we crossed the Arctic Circle in fog and calm airs. Near Sisimiut, a black ooze in the bilge revealed that Mo’s little red engine (a 48-horsepower Bukh diesel) had burst an oil seal. What luck! In the last-explored parts bin of the town’s snowmobile shop, I found a lone replacement. Finally, in Sondre Upernavik, we took fuel by dinghy for the 400-mile crossing of Baffin Bay, filling all of Mo’s 14 gerry cans for the first time.

The crossing was gray and flat and not much else. On August 9, the approach to Pond Inlet, our first waypoint in the Canadian Arctic, was ice-free, as was Navy Board Inlet and the approach to Tay Bay two days later. Even the run up Lancaster Sound presented glassy, open water, with here and there a brilliant berg. Still, each report from Environment Canada showed persistent close-pack inside the passage. Only slowly was the archipelago releasing its winter wealth.

I am often told by those in the know how much easier a Northwest Passage is today than it was in 1975 when Willie De Roos and his strong steel ketch fought for every mile. Climate change has turned an ice passage into a lake passage with but an occasional frigid encounter, say these experts. There might be truth in this, but it misses the point.

I bought a rifle for defense against the polar bear. The attendant took my cash and handed over the firearm and shells with as much concern as if I were buying a quart of milk.

For a westbound yacht, the Northwest Passage—especially between an entrance at either Prince Regent Inlet or Peel Sound and the later exit at Cape Bathurst—is a maze of sometimes narrow, often shallow and poorly charted water. Here the pack can become trapped, swirling on local currents but unable to flush to sea; it must melt to clear the way. Moreover, though strong, Mo is not an icebreaker. Pack covering an area from one point to the next can stop us cold, and when that gate opens, allowing further progress into the maze, a gate ahead or astern might close and possibly remain so for the duration. The risk is of finding oneself deep inside enemy territory with no ability to advance or retreat, facing the prospect of a 10-month freeze.

Graham Harbor was eerie. The cove is small, and depths are too deep with a bottom too rocky for good holding; the crowding mountains threaten williwaws and put the boat in a cold shade. Three times the anchor merely clanged across the bottom before catching by a fingernail. I set the drag alarm and prepared for a night of poor sleep.

After dinner, I reached out to ice guide Victor Wejer for one final consultation. “Prince Regent Inlet remains impenetrable,” he responded. “Absolutely no chance that it or Bellot Strait will be available to you this year. Peel Sound is your only hope.”

Over the previous few days, the pack had begun to move in Peel Sound, but this was meager encouragement. The color-coded charts from Environment Canada displayed long stretches of orange (indicating surface-ice concentrations of seven- to eight-tenths) from its entrance all the way to Cape M’Clure. Below Franklin Strait, great masses of ice flowed down from M’Clintock Channel, and here the chart remained resolutely red (indicating surface concentrations of nine- to ten-tenths ice). Worse, the 165-mile run from the intersection of Lancaster and Peel to the first tenuous anchorage at False Strait provided no secure hiding places.

I knew from Victor that other yachts were having to battle in this section. Inook had punched south of Bellot Strait; friends on yellow-hulled Breskell were in Peel, with Altego and Morgane nearby. These boats had crews who worked the ice from the bow with long poles, wedging through the pack, clawing for every inch. “Alioth is a day ahead of you and reports it took 12 hours to pass from Hummock Point to the Hurditch Peninsula,” he reported. I went to the chart and measured it off: 12 hours to go 40 miles.

All day as we crossed, the fulmars flew the other way, out from the ice maze ahead, down Lancaster Sound, into Baffin Bay and south. The fall migration had begun.

“This is a difficult year,” Victor wrote. “Most sailboat crews fight tooth and ice pole to get through Peel. But there is no option. It is time to take your difficult bite.”

August 16, Lancaster Sound

Mo and I departed Graham Harbor under power at 0400. Already the sun sat two hands above the horizon, brightening the fluted cliffs of Devon Island as we emerged from the darkness of the anchorage. Not a breath of wind. The sea, a navy-blue mirror. I made our course west-southwest for the entrance to Peel Sound, distance 120 miles.

All day as we crossed, the fulmars flew the other way, out from the ice maze ahead, down Lancaster Sound, into Baffin Bay and south. The fall migration had begun. We were pushing against the stream.

By midnight, the headlands of Prince of Wales Island had covered the sun. During our 20 hours from Graham Harbor, at least one white chunk had always decorated the horizon, and now being off watch for more than 15 minutes was too long. Given the difficulties of the next leg, I decided to take one last, long sleep. Off Cape Swansea at the head of Peel Sound, I hove to and shut down the engine. Mo drifted slowly northward. I crawled into the sleeping bag, but I could not find sleep. Worry brought me on deck every hour. At 0400, I rose and made coffee and a hot breakfast. By 0500, we were underway.

August 17, Peel Sound

It was clear and calm again. As we motored hour after hour, each notation in the wind column of the log read, simply, zero. Bright sun, warm on face and hands, produced temperatures in the cockpit of 50 degrees F. With no ice in sight, I set about chores: topping off the fuel tanks from the gerry cans, lifting the hydrogenerator, and removing the windvane water paddle from the transom. Neither would be needed for many days, and either could be fatally damaged by a nip from the ice.

By 1100, we had crossed Aston Bay in open water, but two hours later, Mo moved through long, low plains of two-tenths ice off M’Clure Bay. I disengaged the autopilot and took the tiller. Easy-going: The ice was rotten. Some pieces appeared to be nothing more than floating snow; others had been eaten by the warmth into the shapes of pale green and white mushrooms or were canted at strange angles like Titanics forever on the verge of sinking. I pushed Mo at full speed and kept an eye forward for more.

From abreast of Hummock Point, I saw solid white on the horizon, which the day’s mirage transformed into the crest of an ivory tsunami rolling toward us. Soon we moved through more ice than water, but with care and concentration, I could always find a lane just when it was needed. Mo, a heavy bird, swooped and dodged through the floes; I exercised the tiller as if it were the handle of an oar. And it was exhilarating, the constant motion, the rapid decision-making. We can do this, I thought.

Only once did I screw up, and this was by aiming to split two close floes; too late I saw the diagnostic light-green water between them, indicating their connection below the surface. Mo thunked quietly; then there was a clinking sound like ice cubes in a glass. Astern, the floes drifted apart.

Ice went thin, then thick, then thin again. Sometimes the way ahead seemed closed until we were right up at the pack edge, then a sliver of water. We’d follow slowly, feeling a route as much as seeing it, then a pause. I’d climb to the spreaders, searching the whiteness for dark veins. Then onward and out. I’d heave to for a cup of coffee or can of soup, then we’d be back at it again. Hours passed this way, and I was still working the tiller.

By 2300, what had been heavy-going began to thin. The water was clear enough that my course changes were slight, mere nudges of the tiller between my legs, my hands in pockets for warmth. I played the dangerous game: How little could I change course; how close to the ice could I safely get? Only occasionally there was a miss, proof being a soft swooshing on the hull and a smudge of black bottom paint on the passing floe.

Midnight: The western sky burned orange, but to the east it was a frigid purple with a full moon over a low silhouette of hills. Such perpetual dusk made for difficult seeing, but here the floe was odds and ends. I had been hand-steering for 20 hours. Fatigue weighed on leaden eyes; my thighs were shaking.

Ahead at last was a long, dark opening as wide as the sound. Clear water. The faint white on the horizon must be a whole 10 minutes distant. I flipped on the autopilot, dropped below, and set the alarm for a five-minute nap. I collapsed against a bulkhead, immediately asleep.

Then on the fourth minute, a heavy crash. Mo shuddered as if hitting a wall and stopped dead. The engine ground right down. I leapt for the throttle, backed her off and then looked forward. Mo and an ice block the size of a bus were drifting slowly apart.

At 0200, there were scattered floes, but we’d gotten past the first plug. A sense of satisfaction, and still we motored south. Finally, to the east I saw the expected cut in the land, False Strait, where we dropped anchor at 0600. We’d come 150 miles in 26 hours and were through Peel Sound.

August 18, Tasmania Islands

At noon the next day, the anchor came up clean, the tip shining bright—another rocky bottom. Over a quick morning coffee, I pulled an ice report and then also noticed a message from the crew of Alioth.

Hailing from Belgium, Alioth is a 55-foot aluminum expedition sloop we’d met for the first time in Halifax. Here I’d gotten to know her crew of three: skipper, Vincent Moeyersoms, with Olivier and Jean, brother and friend, respectively, experienced sailors all. After a day of outfitting, we would meet to compare notes over a beer, and I came to admire Vincent’s thoughtfulness and his careful preparation. Still, one cannot anticipate every eventuality. This morning’s message said that Alioth’s gear box had failed (who carries a spare gear box?). Now she was without propulsion in five-tenths ice south of the Tasmania Islands, some 75 miles from our position. She’d have to sail the 250 miles to the next village, Cambridge Bay, for repairs, and was asking if we would join her as escort. I quickly got us underway.

As we steamed southwest, I could see heavy floe issuing from milewide Bellot Strait as a continuous sheet. How fortunate we were to be heading away from it; how unfortunate that within 10 minutes we had entered an obliterating fog. I reduced speed to 4 knots and began to pick my way through loose pack. It was easy-going enough, but I had no idea what lay ahead or if my lane would remain clear.

The cold was nipping hard. My hands were in a triple layer of fleece and leather mittens, but the mitt on the tiller felt as thin as paper, and that hand soon ached. Toes were numb in their insulated boots, even after stamping in place. And so painfully slow was our progress! I began counting off the seconds between when ice became visible and when it passed abeam. At first the count was five. When the fog dissipated enough that I could count to 10, I put Mo at full speed.

We approached the Tasmania Islands in late evening; here the deck lifted and the ice thinned to mostly open water. I knew that I needed a short sleep before encountering the unknown with Alioth, so I decided to risk the pass between the easternmost Tasmania island and the mainland. Depths were not marked on my chart, but I had faint recollection of Bob Shepton having been through here in Dodo’s Delight in 2013, and a divot in the coast catty-corner from Cape Rendel looked like a promising catnap anchorage.

It was nearing midnight when we made the entrance, and here we passed a solid line of growlers grinding together where tidal streams met. Inside the pass, the current pushed against Mo, and our way slowed dramatically. Worse, the cut was full of brash and scattered floe. With such a current, the anchorage I’d hoped for would be too easily swept. There would be no stopping after all.

The bottom continued to be uniformly deep mid-channel, but ice kept me at the tiller. In the darkness, fatigue and cold bore down and were moderated only by the sense of risk and the need to keep moving. By 0400, we had exited the pass and were back into the relative safety of the strait. Exhausted and shivering, I hove to, shut down the engine, made a can of soup, and went straight to my bunk.

RELATED: Sailing the Southern Ocean

Two hours later, I woke to a heavy thud against the hull. Already the day was squintingly bright, the sea a solid white all around as Mo lay gently heaving in close-pack. From the pilothouse, we seemed penned in, but from a perch on the gooseneck winch, I found the floe looked loose enough that we could make slow way to the southeast. Alioth lay to the southwest, half a day away, and where, according to Vincent, she was jogging back and forth under mainsail in the gut of a large opening. Vincent reported solid pack to his north, east and west, but he could see what appeared to be a clean lane due south. That was good news indeed, but would it last?

By 1400, I’d worked below a solid line of pack separating our two vessels, and then was able to swing due west toward Alioth’s position. An hour later, her sleek gray hull came out of the mist where she was hove to in a cove of blue surrounded by sparkling, icy shores.

“Nice to see a friend,” Vincent reported on VHF. “Our lane seems to be holding, and there is a north wind.” Alioth spread her wings immediately, and we began to make our cautious way. Sometimes our lane would tighten; at others, it would divide, and then Vincent and I would study what we could see in binoculars and negotiate over VHF which path we thought best. Each decision, so made, paid off. Three hours later, the lane became so wide and straight, it was as if Moses had parted a sea of white. Then suddenly, the ice receded altogether. We were below the second plug. Alioth made a close approach to Mo, and we four cheered our good fortune.

We knew current from M’Clintock Channel had pushed its pack well out into our preferred route, so we continued south until nearly aground on Clarence Island. Then we wore toward Victoria Strait in open water. Overnight, our two vessels sailed in company in a beautiful following wind, and around midnight, Alioth took the lead and kept watch while I rested below. Twice the VHF barked, “Moli, wake up. Growler to port; do you see it?”

In the Arctic, a sailing wind is rare and short-lived. Thus, the next day came on gray, the sea greasy smooth; with it arose a new problem. We were becalmed 100 miles from the shelter of Cambridge Bay, and though this presented no serious difficulties for the moment, the forecast called for an intense westerly gale to sweep our quadrant two days hence. Our position well north of Jenny Lind Island provided no room for running off or lying to a drogue in a blow that would work to push us back onto the ice we had just escaped.

I offered to take Alioth in tow, but Vincent refused. He didn’t wish to risk another man’s engine—and by extension, a successful passage out of the Arctic that season—just for the sake of his own. He countered that we should proceed to safety without them, an offer I found equally unsatisfactory. Having achieved stalemate, we drifted in company most of the day, taking a little breeze now and again for a mile or two, and until the evening forecast insisted we acknowledge the coming danger.

Mo pulled alongside Alioth in the twilight. Vincent lifted over a yoke and towline, which I took and secured. I throttled up the little red engine; the line came taut, and the two vessels were underway at 4 knots for Cambridge Bay. All night we motored and into the next day. Gradually the sky lowered and grew threatening, but still there was no wind. In the late evening, we entered the long channel to Cambridge Bay. Then we were inside and steaming up the welcome confines of the West Arm. At 2300 on August 21, I cut loose Alioth over her chosen spot, and her anchor splashed down. I moved farther up-bay and let go Mo’s hook in 35 feet.

In the night, the gale came on as foretold. From my bunk, I could hear the rigging roar as it had not done since the Falklands. Mo started at her snubber, but the holding here was ancient mud and the anchor lay buried far, far to windward. I eased deeper into the down of the bag and fell asleep listening to the blow.

Homeward Bound

A few days later, Mo and I left Alioth in Cambridge Bay to await spare parts, and at Cape Bathurst, we departed the ice as well. On September 12, we crossed the Arctic Circle headed south; we stopped in Nome, Alaska, the next day, made Dutch Harbor on September 20, and returned to our home port of San Francisco on October 19, 2019, completing the Figure 8 Voyage in 384 days.

Randall Reeves is a West Coast sailor, writer and adventurer. For more about his Figure 8 Voyage, check out his book-length account, available at figure8voyage.com.