An autumn passage from the US East Coast to the Caribbean is one of sailing’s great adventures. Every fall, hundreds of sailing yachts make this voyage—alone, with a buddy boat, or in a rally. No matter which route you choose, it’s approximately 1,500 miles, taking eight days to two weeks of sailing time in the Atlantic, over the Gulf Stream, and through the Bermuda Triangle. There’s a high probability you’ll be hit with a 30-plus-knot cold front and a couple of squalls before you pick up the trade winds for a few of days of delightful beam-reach sailing into the islands. Here’s a look at three ways you can head south.

Option One: From Newport, South

Being from Maine, I used to sail down to Newport, Rhode Island, for the boat show in September, and then leave for Bermuda when the forecast was favorable. At that time of year, the weather windows are usually wide open. I’d keep an eye on the tropical weather and, if no storms were brewing, I’d leave, knowing I’d get to Bermuda in five days, before a hurricane could form and beat me there.

More recently, I’ve taken to joining Hank Schmitt and other delivery captains on the North American Rally to the Caribbean, which departs from Newport in late October. Schmitt has been organizing the NARC Rally for the past 24 years and is planning on turning over the tiller to the Salty Dawg Sailing Association in 2024.

This Newport departure leaves on northwest winds of 18 to 25 knots. With the wind astern, it’s 200 nautical miles—about 33 hours—to the Gulf Stream. Pick a waypoint on the north wall of the stream, west of the rhumb line. By the time you exit the stream 10 hours later, the 3-knot current will have swept you 30 miles east, putting you back on the rhumb line. With the stream behind you, it’s time for T-shirts and shorts.

Bermuda is just 360 nautical miles ahead—two and a half days away. You’ll see Bermuda’s lights hours before landfall. The last time I made this trip, in 2021, we got there in three days and 20 hours, with winds no stronger than 25 knots all the way.

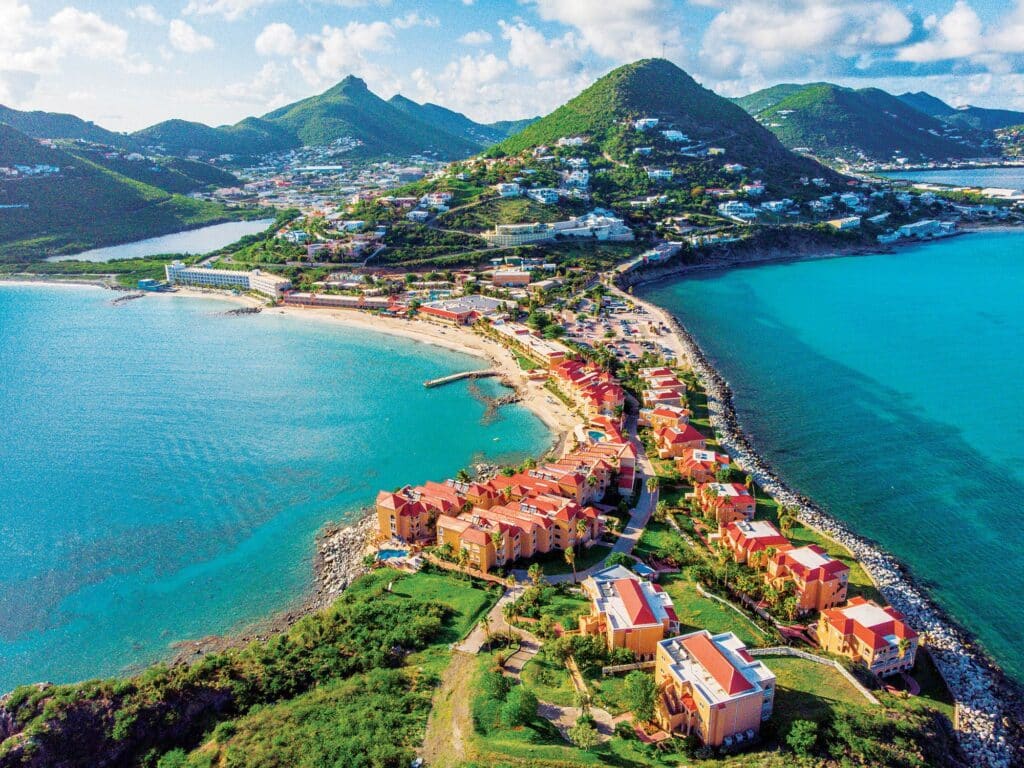

Wait in Bermuda a few days fixing stuff, reprovisioning, taking on fuel, socializing, enjoying the island, and resting up for the 850 miles from Bermuda to St. Maarten, or 950 miles to Antigua. Five to eight days in length, this second leg of the voyage will be a great deal more enjoyable. The worst is behind you.

This stop in Bermuda is my preferred route, even if I depart from Chesapeake Bay.

Option Two: Departing the Chesapeake

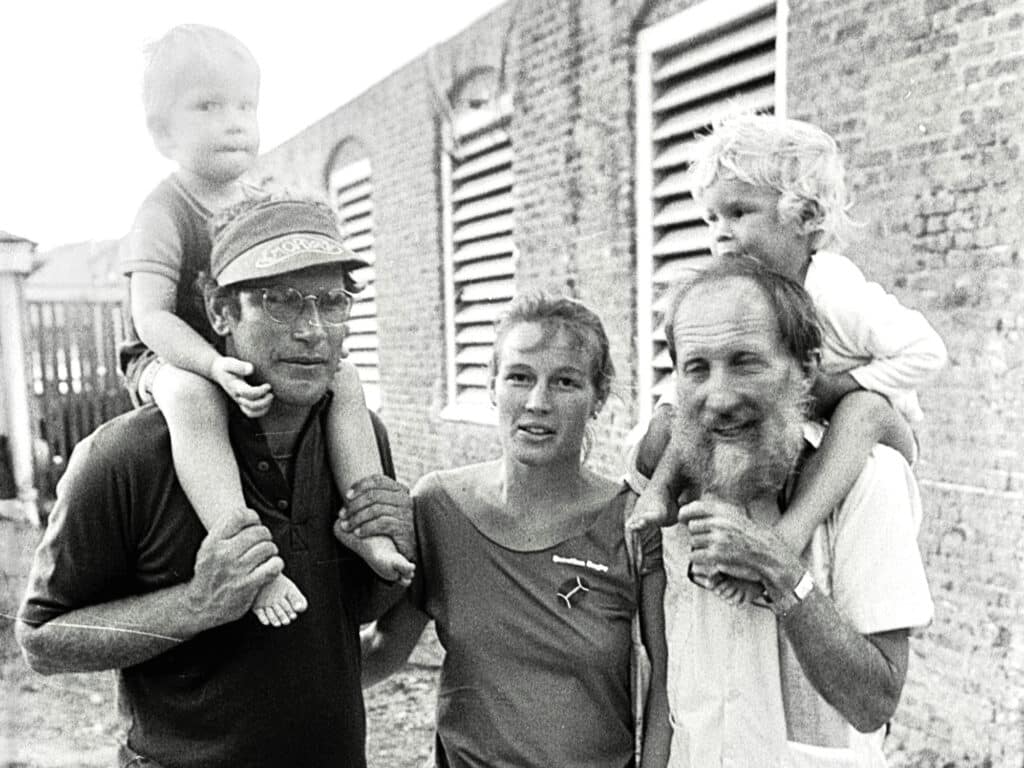

Leaving from the Chesapeake means that the Gulf Stream is only 100 miles offshore. You’ll be across it within 24 hours. Don Street, the old guru of sailing, says that if you are already south and west of Newport, your best bet is to depart from the Chesapeake, or farther south. (Street’s first published article was advice on sailing south, 60 years ago in Yachting, September 1964.)

Leave on a northwest cold front, and you’ll have the wind abaft the beam for two or perhaps three days.

This popular route is a 1,500-nautical-mile east-southeast arc out into the Atlantic before turning south. It’s a seven- to 12-day nonstop voyage, with two to six days of motoring through the Bermuda Triangle. While this route bypasses Bermuda, each year, a few boats stop there for fuel, rig or sail repair, or to just break up the long voyage.

Boats need to have fuel for at least five days of motoring, and food for three weeks. Each year, a few boats run into problems with steering, the rig, fuel or seasick crew, and they retreat. Better to be prepared.

If the weather has you bottled up in Hampton or Norfolk, Virginia, you can motor down the Intracoastal Waterway. The rule on the ICW is 63/6 (meaning a 63-foot mast height to get under the bridges and a 6-foot draft so that you don’t run aground). In three days, you’ll be in Beaufort, North Carolina, a wonderful town with three marinas. From there, the Gulf Stream is only 50 miles offshore. You’ll be across and into warmer weather in 15 hours, and then it’s a similar course as those departing from the Chesapeake.

From Beaufort, you can also meander farther down the ICW, or sail slightly offshore inside the Gulf Stream, ducking into ports when necessary, all the way to Florida.

Once in Florida, you have your pick of departure ports: Fernandina, Palm Beach, Fort Lauderdale. In late November and December, watch the weather carefully.

“When a good hard norther threatens, leave 24 hours before,” Street says. “Place a pound of butter on the main cabin table, head east-southeast until the butter melts, and then turn south. Then, head southeast, and you might actually arrive in St. Thomas on track all the way. These are the same sailing directions that have been given for probably 300 years.”

If the weather in the Bermuda Triangle is unfavorable for making the offshore voyage, there’s the Thornless Path.

Option Three: The ThornLESS Path

If you are departing from anyplace in Florida, and if the winds in the Bermuda Triangle are nonexistent or contrary, then hopping down the Bahamian chain is an option. You can sail down the chain either outside to the east or through the chain itself. The latter requires stops to anchor each evening. Joan Conover, president of the Seven Seas Cruising Association, has sailed the Thornless Path a few times and favors it as a route south. Bruce Van Sant’s book The Gentleman’s Guide to Passages South maps out this route in detail.

The Turks and Caicos is a jumping-off spot for the slog south and east to the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the Eastern Caribbean. Traditionally known as the “Thorny Passage,” it’s a windward bash against the trades, current and swells, but it can be done; just stay clear of Haiti. There’s a process that savvy skippers use of sailing at night along the coast of Hispaniola.

In the Dominican Republic, you’ll find the Caribbean of 50 years ago. YouTubers have posted videos on finding the ports of entry, crossing the Mona Passage, and understanding the route along the south coast of Puerto Rico. Noonsite.com has up-to-date information on port entry, marinas, services and restrictions.

Getting Ready

No matter which route you decide to take, the journey starts with planning and preparation. My pre-departure checklist is eight pages long. Here are a few things to consider.

The boat: Is it seaworthy, capable and ready? Is it designed and built for an offshore voyage, or for coastal cruising or racing? Inspect everything from stem to stern, masthead to keel, and hire a surveyor to catch things you’ll miss. Your insurance company might insist that you have a recent survey anyway. Get it done early so that you have time to make repairs. Be there to watch and ask questions. Also have a professional rigger and an experienced diesel mechanic do inspections. Grease the steering system, and tighten the bolts in the quadrant. Find and test the emergency tiller. Is the rig set up for offshore, with an inner stay on which to hoist a staysail, or a Solent stay? Can the boat be reefed and hove-to easily? Are the bilge pumps adequate? Is all the safety and person-overboard gear up to date?

Supplies: You’ll need to carry enough fuel for five days (100 hours) of motoring, plus drinking water and provisions for three weeks. Remember to bring enough toilet paper. I forgot once. Had to turn back.

The crew: Have at least two or three seasoned sailors with you who don’t get seasick, can stand a solo watch, and know what to watch for. I find crew on sailopo.com, which is free. Your insurance company might want to see résumés from you and each crewmember, and might insist that you hire a pro skipper. If you want to crew on somebody else’s boat, a two-week training voyage can cost $4,000 to $6,500.

The weather: No matter the route, the weather tells us when to go—or not. Rallies provide a pre-departure weather briefing and daily updates at sea. You can retain your own weather-routing service, or you can do your own forecasts underway with an online service such as predictwind.com or windy.com.

Resources: In addition to the resources listed throughout this article, I find it helpful to have copies on hand of Street’s Cruising Guide to the Eastern Caribbean and Transatlantic Crossing Guide by Donald M. Street Jr., World Cruising Handbook by Jimmy Cornell, Sailing a Serious Ocean by John Kretschmer, Offshore Sailing: 200 Essential Passagemaking Tips by William Seifert, Handbook of Offshore Cruising: The Dream and Reality of Modern Ocean Sailing by Jim Howard, and Ocean Sailing: The Offshore Cruising Experience With Real-Life Practical Advice by Paul Heiney.

David H. Lyman is an award-winning writer and photographer based in Maine.