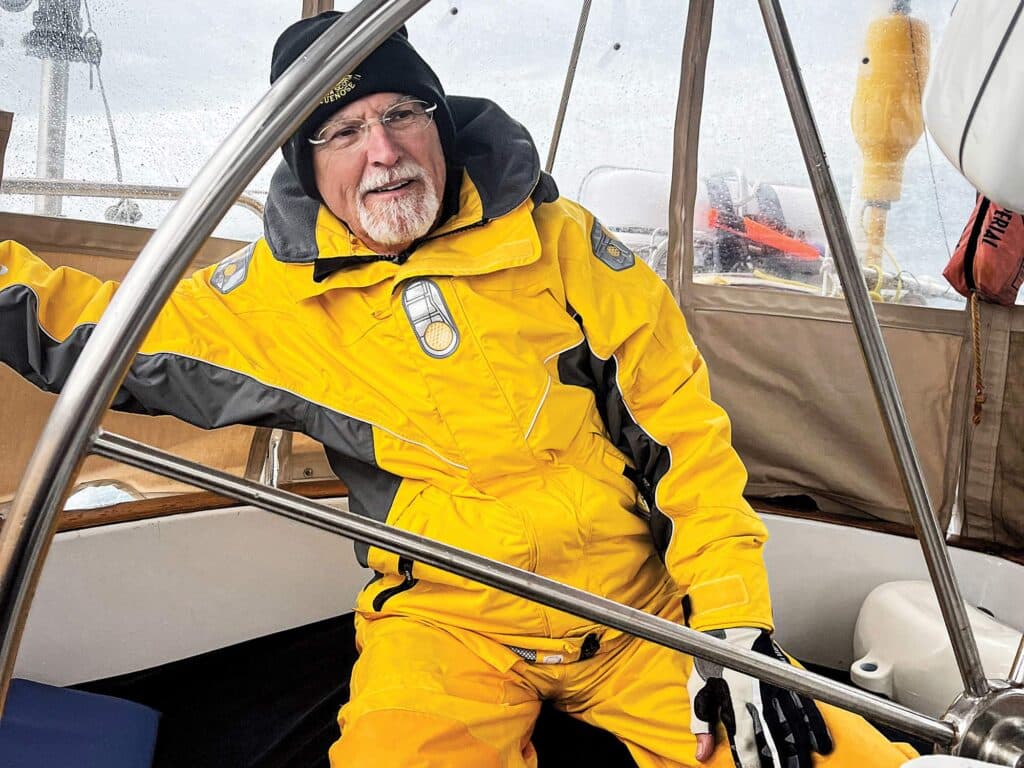

Quetzal had recently glided into Lunenburg Harbour under spinnaker, five days outbound from Bermuda. It was great to be back in one of my favorite Nova Scotia haunts, and time to get serious. Polar Sun, my friend Mark Synnott’s Stevens 47 cutter, was also in Lunenburg. Mark is a climber, professional adventurer and bestselling author. We had most recently sailed together in Grenada, and now he was also bound north, leading a National Geographic expedition through the Northwest Passage, hoping to find new evidence about the fate of British explorer Sir John Franklin. We gathered in Quetzal’s salon and chatted long into the night, discussing our preparations and aspirations for our upcoming voyages.

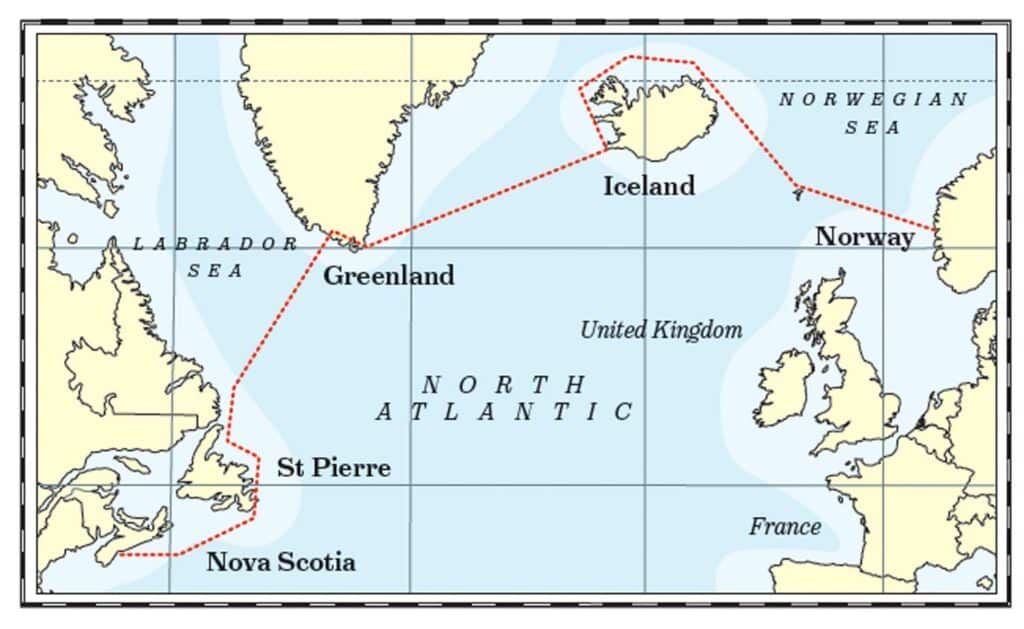

On June 15, Quetzal slipped her mooring and steamed into the fog. It was reassuring to have Alan, a dear friend from Lunenburg, back aboard. Ron, a Quetzal glutton who has crossed the Atlantic with me twice before, and Mark, a terrific shipmate from Montana, completed the crew. Our job was to sail to Newfoundland, where our Viking voyage would commence. However, our first landfall was fabled Sable Island, a crescent of shifting sands 90 miles south of eastern Nova Scotia. It’s notorious as the “graveyard of the Atlantic,” and more than 350 wrecks form a necklace of tragedy. It’s also home to an unlikely herd of 500 wild horses. It’s also not easy to visit, so when Alan arranged a coveted landing permit, we had to stop.

After a two-day sail from Lunenburg, we dropped the hook just off Sable’s northern shore. We hailed the park authorities, launched the dinghy, and prepared for a beach landing. There are no harbors on Sable, and landings often go badly because of stealthy wave breaks. We were the first boat to arrive in 2022 and had been warned not to attempt to get ashore unless the conditions were favorable. It was calm and clear as I searched for a stretch of beach with a minimal break and then gunned our 6 hp Tohatsu. In my mind, we were marines storming a beach. As the dinghy plowed into soft sand, a modest wave plopped aboard. We struggled to jump out and haul the dink up the beach. Reality hit with the second, soaking wave. We were four post-middle-aged guys in an overloaded dinghy, but we were ashore on Sable Island.

The park rangers helped drag the dinghy to a spot beyond the reach of the tide. Trekking through sand and marram grass, we encountered the horses. Perched on a low dune near a freshwater pond, we observed an injured stallion fend off unwanted inquiries from a pair of frisky colts interested in his harem of mares. The once-proud stallion was limping badly, and Mark, a veterinarian, assured us his days were numbered. Parks Canada has a hands-off policy concerning all wildlife on Sable, where the horses, introduced in the 1700s, have thrived. Originally from Acadian stock, they have developed into a unique breed to withstand the harsh climate of the North Atlantic. As we made our way back to the beach, we encountered a plump of gray seals, and a few curious harbor seals, a mere fraction of the thousands of seals that breed on Sable.

With strong winds forecast by late the next day, we decided to cut short our visit and head for Newfoundland. After a breezy passage across the Grand Banks, we made landfall in St. John’s. We secured every fender we had and eased alongside an unfriendly wharf. Alan’s friend Mike Riley delivered two beefy 12-foot spruce sections that we later fashioned into ice poles. In the spirit of Viking plundering, we enjoyed great food, drinks and Irish music along George Street, whose claim to fame is having the most bars per square foot of any street in North America. Continuing north, we made landfalls in Trinity, Fogo and Twillingate before arriving in Lewisporte, a small town with the nicest marina in the Canadian north.

The crew for the next leg, the challenging 1,800-mile, 18-day passage to Iceland by way of Labrador and Greenland, turned up on July 7. Scott, Antonio, Levi, Brian and Jeff had all sailed aboard Quetzal before, some many times and most across an ocean. After a dry run of stuffing ourselves into survival suits and a sobering safety briefing—falling overboard was a very bad idea—we shoved off for an overnight passage to L’Anse aux Meadows, the only documented Viking settlement in North America and a national historic site administered by Parks Canada.

We had icebergs on our minds. Environment Canada provides ice updates online, and I studied them daily. I also downloaded the app Iceberg Alley, which documents icebergs and whale sightings. There were reports of a few stray bergs along our route, and we kept a sharp lookout through the night. We didn’t see any icebergs, but a pod of minke whales escorted us around Cape Bauld at the tip of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula.

As the dinghy plowed into soft sand, a modest wave plopped aboard. Reality hit with the second, soaking wave. We were four post-middle-aged guys in an overloaded dinghy, but we were ashore on Sable Island.

We came alongside a new wharf at Garden Cove. Two local fishermen took our lines. They didn’t seem to mind the driving rain and near-freezing temperatures. When I told them that we were headed to the nearby park, one informed me, “You can’t walk there from here.” I was surprised because it was just over a mile away and I’d made the walk before. “Nope, can’t walk there. It’s too wet. But you can take Rabbit’s truck. Keys are on the dash.”

The visitor center at L’Anse aux Meadows, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, details the Vinland voyages of the Vikings, who reached this faraway shore sometime around 1000 A.D., nearly 500 years before Columbus. Sagas, originally oral histories, tell the story of Leif Erikson’s voyage to Vinland. With a crew of 35, they departed Greenland and made their way north and west. Their first landfall, which Erikson dubbed Helluland, or place of stone, was likely somewhere on Baffin Island. It was a forbidding land, and they sailed on. Their next landfall, Markland, meaning wooded land, was probably along the Labrador coast, but they didn’t tarry and rode a favorable northeast wind farther south. Finally, they came to the shallow, rocky anchorage near today’s L’Anse aux Meadows and decided to make the grassy knoll overlooking the harbor the first European settlement in the New World.

The term Vinland, or place of grapes, has historically been problematic. The sagas are clear that when Erikson sailed for Greenland the following spring, his cargo included grapes and vines. While it is unlikely that wild grapes have ever grown in Newfoundland, the Norse artifacts at L’Anse aux Meadows are indisputable evidence of a settlement dating from around 1000 A.D. First discovered by Norwegian archaeologists Helge and Anne Ingstad in 1960, these remains are of Norse-style sod buildings, including a forge and small shipyard. Artifacts include slag from forging, numerous iron nails used for shipbuilding, and more than 50 wrought-iron pieces. It is possible, or even probable, that Erikson’s landfall was farther south, and many historians now believe L’Anse aux Meadows may have been where his brother-in-law, Thorfinn Karlsefni, tried to establish a permanent settlement a few years later. Hiking around the respectfully restored site in a bone-chilling rain, I had deep respect for the men and women who sailed from Greenland in a low-slung boat, probably less than 60 feet long, with a single square sail and only their natural instincts to guide them.

That night, one of the local fishermen provided the crew with lobsters for a feast. Before we shoved off the next morning, Scott took a swim, an invigorating ritual he undertook at every landfall, even when we were surrounded by ice. We made our way across the Strait of Belle Isle and approached mainland Labrador. Fog closed in as we neared Battle Harbor, but, undeterred, we threaded our way through a maze of rocks, racing darkness to the wharf.

Battle Harbor occupies a rocky outcropping that is steeped in history. A Marconi wireless tower was raised in 1904. Five years later, Robert Peary used the tower to telegraph news that he had reached the North Pole. Reporters from all over the world were dispatched to Battle Harbor, though today, significant historic and scientific research has concluded that he most likely did not reach the pole.

I had deep respect for the men and women who sailed from Greenland in a low-slung boat, probably less than 60 feet long, with a single square sail and only their natural instincts to guide them.

Continuing up the Labrador coast, we finally encountered an iceberg. It was a classic wedge berg, and we cautiously sailed toward it. I used my sextant to measure its altitude and the radar for a distance off reading. A quick calculation put the iceberg at more than 160 feet high and about 250 feet wide. We were in awe and shot photos from every angle, paying homage to the giant castaway from a distant glacier. Little did we know that a week later, we’d be routinely punching through ice-choked waters, casually dismissing isolated bergs like this one while searching for passages through sea ice.

We anchored in Eagle Cove, a fishhook-shaped harbor carved out of Hawk Island. This was genuine wilderness. We had been warned by veterans of Arctic travel to be on guard for polar bears, and some suggested that we carry a gun for protection. Instead, we carried bear banger cartridges and a pen launcher, which travels about 100 feet and then explodes with a mighty blast. It would certainly get a bear’s attention.

Scott and Brian were a long time ashore before I noticed them in a distant corner of the cove. When I retrieved them in the dinghy, there were shivering in their underpants. They had discovered a bed of mussels and braved frigid water to stuff their pants with hundreds of them for dinner.

After a swift passage through a steep-sided strait intriguingly called Squasho Run, we made our way offshore. We timed our departure to catch strong but favorable winds on the back side of a deep low-pressure system, and to have as much daylight as possible to get beyond the numerous icebergs that Environment Canada’s weather and climate-change website assured me were hovering near the coast. The first 24 hours were rough as Quetzal ran before near-gale-force westerlies while being rocked by seas from every direction. Not for the first time, we came to appreciate the hard dodger and full enclosure that kept us dry and warm. A day later, conditions moderated, and soon we were under power gliding over quiet seas with a squadron of fulmars tracking our every course correction. On Day Four, 60 miles from land, we encountered many large icebergs. Then, through a clearing in the low clouds, Brian spotted the towering, snowcapped mountains of southwest Greenland. We were entering another world.

Icebergs come in different shapes and sizes. The big ones, which are masses of frozen fresh water, are generally easy to pick up on radar. Bergy bits, usually fragments of larger bergs, are 3 to 12 feet high and more worrisome to sailors, especially in bad visibility. Growlers, which occasionally hiss or growl as trapped air escapes, are 3 feet or less above the surface but can be deadly. They’re typically around 200 square feet in size but can weigh up to 1,000 tons. Imagine smashing into a growler at 6 knots.

With the sun shining, Levi launched his drone. He managed to land it on deck while we sailed between bergs. In addition to beautiful photos, it was also nice to get a view of what lay ahead. The wind freshened as we made our approach. We tried to stay upwind of the larger bergs, knowing that bergy bits and growlers were likely to be on the lee side. We slipped around several growlers, and one small berg that tried to block the entrance to the town of Qaqortoq. Its harbor was crowded with local boats, so we tied up alongside the commercial dock. Later, we moved across the harbor to an open fishing dock. Finding secure dockage in Greenland requires that you be ready to move when a commercial ship arrives and that you have long lines with chafe gear and heavy-duty fenders.

Qaqortoq, the largest town in southwest Greenland, is also close to the site of the Vikings’ original Eastern Settlement. Founded by Erik the Red, Leif’s father, around 980 A.D., the settlement remained vital into the 14th century. Several Norse remains are visible in nearby fjords. We took on provisions, topped off our fuel and, surprisingly, had a delicious Thai meal in a small restaurant in the port.

In Greenland, I shifted my attention to the excellent daily ice reports provided by polarportal.dk, a Danish ice- and climate-monitoring institute. Our intended route was to follow an inside passage south to Nanortalik, then enter Prince Christian Sound. This spectacular 70-mile passage north of storm-ridden Cape Farewell provides a protected channel to the Irminger Sea and the east coast of Greenland. Protected, that is, if you can get through the ice. We were now worried about sea ice, or storis, which is frozen seawater that forms quickly and disappears just as quickly. Driven by wind, current and bathymetry, storis can completely block a passage. Looking ahead a week, our planned exit would likely be blocked by ice.

High-latitude sailing and planning don’t mix. You take things a day, or even an hour, at a time, then react to drastic changes in weather and ice conditions. We had a hard upwind slog from Qaqortoq, tacking and motorsailing to stay clear of hundreds of large icebergs and countless smaller ones before finding an open spot along the wharf in Nanortalik. It’s a quiet village whose name translates to “place of polar bears.” The protected harbor provided a respite from the strong winds.

The following day, July 19, we picked our way through minimal sea ice and entered the Ikerasassuaq Strait. Gale-force north winds were forecast, so we made our way to a landlocked bay, Paakitsuarssuaq, and conned our way past rocks and ice into the stunning anchorage.

The passage here is, simply, magnificent. Sheer-sided 6,000-foot mountains explode from the water’s edge, and several glaciers reach down to the sea, calving off bergs and bergy bits. It was calm, and we motored most of the way. Several times we slowed to a crawl, usually just downstream of a glacier, as the channel became choked with ice. Brian and Jeff manned the bow all day long, guiding us through narrow openings and using the poles to shove growlers out of our way. We nosed up to Kangerdluk Glacier and let Quetzal drift. Levi and I stayed aboard, and once again the drone was aloft. The crew took the dinghy to the foot of the glacier and snagged a few nice chunks of ice for captain’s hour.

Luckily, the strong winds of the night before had pushed the storis south, leaving a clear path out. That night was the most stressful of the summer as Quetzal sailed toward Iceland in fog, gusty winds and ice-strewn waters. Jeff was a champion, manning the bow for hours in the dark despite the cold, wet conditions. We monitored the radar and became adept at picking up even very small bergs. It was an incredible relief to finally gain sea room, and the five-day 600-mile passage to Hafnarfjordur, Iceland, was surprisingly smooth.

Quetzal and I took a well-earned break in Iceland. My wife, Tadji, my daughter, Narianna, and her fiance, Steven, flew in, and we toured the island by car. Iceland is a rugged land of fire and ice. The Fagradasfjall volcanic eruption was greeted with nonchalance by locals and intrigue by visitors. Nari, Steven and I hiked 6 miles each way on a rough trail to get a firsthand look at molten lava. Quetzal was treated well by the Icelandic Keelboat Association, and I gave a talk in Reykjavik in appreciation. We toured the Settlement Exhibition at the City Museum. The first humans in Iceland were Viking settlers who arrived around 870 A.D. In just over 100 years, these bold mariners had made their way to Greenland and Canada.

The new crew turned up on August 7, and we were underway the next day. Fridrik, a photographer and dauntless sailor who circumnavigated Iceland solo in his 33-foot X Yacht, filmed our departure. Jim, Chris, Sean and Denise, all Quetzal veterans and good friends, had a lumpy first sail as we pushed north through a leftover swell opposed by strong winds. We decided to take the long way to Norway, along the north shore of Iceland, which would also take us just above the Arctic Circle. We skirted the dramatic headlands of the Vestfirdir (west fjords) and made landfall at Isafjordur, where several sailboats were holed up. They were waiting for the ice conditions in East Greenland to improve before carrying on. In what had become a pleasant ritual, we made our way to the pool for a soak. Every town in Iceland has a pool that usually includes a hot and (really) cold tub. You alternate from one to the other.

We had fair winds as we headed east, rounding the headland of Horn at latitude 66 degrees, 30 minutes. I had a reminder of the many miles Quetzal has before her. In December of next year, we hope to be rounding the other horn, the infamous cape perched at the tip of South America, nearly 7,500 miles of latitude away.

We made landfall at the small island of Grimsey. Known as the “island on the Arctic Circle,” it’s home to 30 permanent residents, thousands of puffins, and seemingly millions of pissed-off Arctic terns that dive-bombed us as we hiked to the monument that denotes the actual position of the Arctic Circle. It’s a massive round block of concrete. It’s round because the circle keeps moving a few feet each year, and it’s easier to relocate a round monument than a square one. That night, Magnus—the busiest man on the island who runs the fuel dock, airport and his own fishing boat—came aboard for a drink. He informed us that the puffins were getting ready to depart. Apparently, a memo goes out, and within a day or two, all the puffins head offshore and don’t return until the following spring. The terns were also getting ready to start their epic migration from the Arctic Circle to the Antarctic Circle and back.

From Grimsey, we made a nonstop passage to the brooding and beautiful Faroe Islands, the next waypoint on the Viking route across the Atlantic. We were never alone; doughty fulmars and soaring gannets kept us company. We hove-to just west of the island of Kalsoy to wait for a 5-knot tidal current to change our way. It’s critical to time the tides right, and the Rak app was incredibly helpful. Riding the current, we zipped through the starkly beautiful Leirvik Fjordur channel and made landfall in the capital of Torshavn. The Faroe Islands need time to explore properly, and the few days we had were not enough. We departed for the Shetland Islands, our final stop before Norway, at 0300.

The morning was clear and the wind crisp. Chris and Jim are devoted celestial navigators, but opportunities are rare in the often cloudy north. This was the perfect morning. Chris skillfully measured the angular distance between the silvery crescent moon and Jupiter, a process called lunar distance, and a challenging sight to take. He then patiently worked Jim and me through the process, and, many calculations later, we were able to check the accuracy of our ship’s chronometer. This technique was used by Joshua Slocum and other early voyagers, which liberated them from the need for accurate timepieces.

The North Sea was determined to keep us from calling at the Shetland Islands. A hard east wind accompanied by 8-to-10-foot seas with an annoyingly short period between persuaded us to carry on for Norway. Denise and Sean took long stints at the helm, conning Quetzal to weather.

The last three days of the crossing proved to be the toughest as we pounded our way east. Conditions finally eased as we approached the coast. We sighted the red-and-white lighthouse on the tip of Fedje Island in the late afternoon of August 19. It was a bittersweet moment for me. Quetzal had completed her ninth Atlantic crossing, successfully retracing the Viking route, the result of two years of planning and three months of challenging sailing. It was hard to believe that we had pulled it together. But as we made our way into the quaint harbor, the only sailboat in sight, I realized that plenty of adventures lay ahead.