Fish on!” Gayle shouted as she jumped up from her seat under the dodger and lunged for a tightly stretched fishing line. After I scrambled up the companionway from where I had been resting below on my off-watch, we quickly worked together to bring in a large yellowfin tuna that had grabbed the lure Gayle had trailed astern only a few minutes earlier. Looking over my shoulder as I stood on the pitching aft deck landing the fish, I peered forward and exclaimed, “Land ho!” In the early morning of our third day out of Pago Pago, American Samoa, two smudges appeared on the ever-lightening western horizon. Our Flying Dutchman 50, Small World II, was bearing down on the Niuas, the northernmost island group of the Kingdom of Tonga.

Wishing to continue our quest of crossing the Pacific on a route less frequented by other cruisers, we had planned this stop at the Niuas for quite some time. Archeological evidence suggests that the Niuas were originally settled sometime around 800 B.C. by the intrepid seafaring Lapita people, who are the ancient ancestors of today’s Polynesians. By the first millennium B.C., it appears the Niuas were culturally a part of the Samoas, and language similarities between Samoan and the now disused Niuatoputapu dialect seem to affirm this. Indeed, the Niuas are much closer geographically to Samoa than to the capital of Tonga.

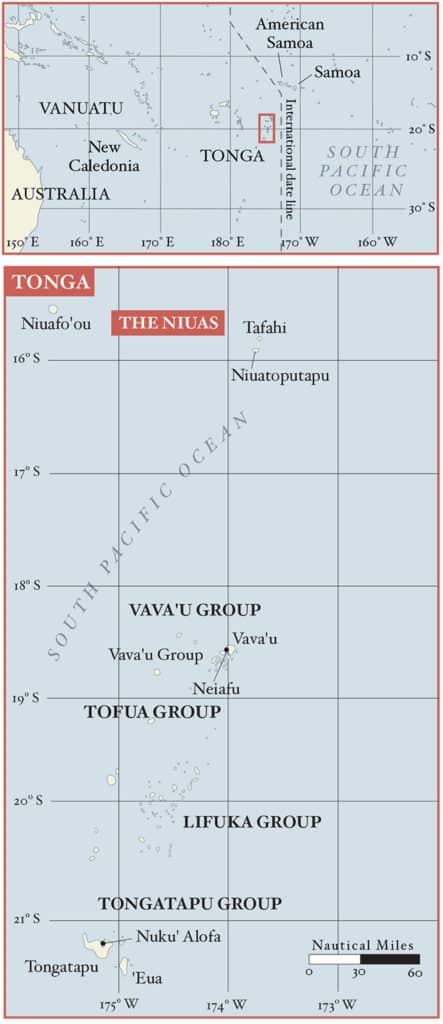

Situated nearly 165 miles north of the more popular cruising grounds of the Vava‘u group, and more than 300 miles north of the capital of Nuku‘alofa, the Niuas consist of three high islands, only one of which has a harbor. Niuatoputapu (pronounced knee-oo-ah-tow-poo-ta-poo) is the largest island and administrative headquarters for the group. Because of its location somewhat off the rhumb line from the Samoas to Vava‘u — and well off the track from Samoa to Fiji — relatively few yachts visit there each year; we were informed upon our arrival in late July 2014 that we were the seventh yacht to visit so far that year.

The Niuas — the two neighbor islands of Niuatoputapu and Tafahi, along with Niuafo‘ou, about 115 nautical miles to the west-northwest — were discovered by Europeans in 1616, when Dutch explorers Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire chanced upon them on their renowned voyage aboard the East Indiaman Eendracht. On that same voyage, they had discovered Cape Horn, proving once and for all that Tierra del Fuego was not part of the alleged great southern continent. Their visit to Niuatoputapu was punctuated with treachery, and twice their ship was attacked. An uneasy truce brought about by the Europeans’ use of modern weapons allowed for some limited trading, but shortly after the second attack, the ship departed. Because of these incidents, the Niuas were known to Europeans for a time as the Traitor Islands. In 1767 Capt. Wallis rediscovered the island of Niuatoputapu and named it Keppels Island. No further significant contact with the Western world occurred until early in the 19th century, when missionaries flooded into the far reaches of the Pacific, effectively bringing an end to the pagan religions and lifestyles of local people.

RELATED: Chasing Whales in Tonga

Entering the pass at 0830, we had no difficulties finding the deep channel, which was marked with massive steel posts just inshore of the seaward edge of the reef and a set of range markers ashore. There were a number of storm-damaged steel channel markers within the reef, which also helped with navigation, although for the most part, they lacked top markers, requiring us to guess at their actual meaning.

Making the final turn into the anchorage gave us the pleasant surprise of seeing a single boat in the harbor: adventurous Italian friends of ours we had last seen in Pago Pago. Unfortunately, they were in the process of upping anchor and grabbing the tail end of the same moderate weather window on which we had arrived to make for Vava‘u, an overnight sail to the south. This left us with a vast anchorage all to ourselves by midday.

Later in the week, the winds cranked up and blew strongly from the southeast. The holding proved to be excellent, with fine, mucky white sand and few rocks or coral heads to cause issues with our anchor rode. The fantastic natural harbor has extensive, shallow reefs offering near immunity from swells from northeast through west, and the shoreline provides protection from east through southwest. Despite the very rough conditions outside the reef during our second week there, we never experienced any uncomfortable seas or surge.

We were lucky our stay there coincided with the king of Tonga’s annual visit. The entire island was in a frenzy of activity in anticipation of his arrival, although the stormy weather outside the harbor had delayed some of the preparations. Usually, one freight ship per month arrives from Nuku’alofa, the capital far to the south, but with the king’s impending arrival, there were to be three ships coming. Because of the rough seas and strong winds, the first ship arrived three days late. Looking out of the pilothouse windows on the morning of its landfall, I saw what appeared to be a fairly small car ferry, which was clearly not designed for open-ocean transits, struggling toward the reef entrance. As it made its final turn and came broadside to the breaking 4- to 6-meter waves, it appeared as if it might capsize. Fortunately, it succeeded in making the turn, and then I watched in awe as the 130-foot ship surfed two of the bigger waves through the entrance into the pass. Quite a sight.

Midday on the day of the king’s arrival by airplane from Vava‘u, festivities began, and virtually every person on the islands of Niuatoputapu and Tafahi was present for the very formal ceremony. Dance troupes of young men and adolescent girls told the story of how their islands were settled and the history of their people through the use of carefully choreographed hand and arm movements and sporadic chanting. The islanders then presented the king with three huge, partially cooked pigs and one immense live boar that took six strong men to pick up in its bamboo cage. We were told later that these were all loaded aboard the king’s airplane and were flown back to Vava‘u. The islanders had created an elaborate display of woven mats and other handmade crafts that were gifted to the king, and also had on display many of the fruits and vegetables being grown on the islands. A bountiful display of fish and shellfish was laid out for the king’s approval.

The diving and snorkeling on the outer reefs just beyond our anchorage were spectacular. With incredible water clarity and healthy, undamaged reefs, Niuatoputapu offers some of the best snorkeling we’ve seen.

Interestingly enough, none of this food was later cooked or prepared, and at no time did we see any refreshments being offered or consumed during the several hours of the festival’s proceedings. This came as a bit of a surprise to us as we had asked the tourism director if there would be food at the festival. Her answer was an emphatic yes. What we failed to understand was that the food there was only for the king’s approval, not for consumption at the festival!

There are approximately 900 people living in the three main villages on Niuatoputapu and another 40 or so on nearby Tafahi. At the time of our visit, there was still no electricity in the Niuas. The islands were devastated by the 2009 tsunami that also affected Samoa, but because the actual underwater quake that caused the tsunami originated very close to the islands, there was virtually no warning. Most of the dwellings in the villages were damaged or destroyed, and nine people died as a result of the churning waters. Aid came in from New Zealand and Australia, and the World Bank also helped with bringing in prefabricated housing. Many of the residents were urged to move farther inland to higher ground, and three satellite villages well inland have been founded. Still, by the time of our visit in 2014, many families were still lacking essential cooking utensils and in need of clothing and school supplies. We radioed friends of ours in American Samoa on their 50-foot Beneteau, Kaija’s Song. They agreed to bring a sizable list of supplies down to the tourism director, Sia, who promised to distribute these essential items to the neediest families on the island. As in many of the other less-visited islands to which we have sailed in both the Pacific and Caribbean, simple things such as underwear, school supplies and bolts of fabric were highly treasured items. Unfortunately, we heard later that some of these supplies might not have been distributed as evenly as we had hoped, but we tried to remember that when people have so little, gifts that literally fall into their laps may not be shared as willingly as our sense of fair play might dictate. With an economy in which the only exports appeared to be handmade woven craftwork, money for purchasing modern luxuries was tight.

Once the winds and seas had finally subsided, we were able to take advantage of the calmer conditions to get into the water. The diving and snorkeling on the outer reefs just beyond our anchorage were spectacular. With incredible water clarity and healthy, undamaged reefs, Niuatoputapu offers some of the best snorkeling we have seen. Seldom visited by people, the outer reefs offer an unparalleled experience but must only be attempted in fairly settled weather. There is at least one substantial shipwreck on the outside reefs that is worth visiting, and one could spend days exploring the many coral canyons cutting in from the outer reef, which harbor myriad species of corals, reef fish and invertebrates. Bring an underwater camera! You might even inadvertently be swimming with whales, which frequent the nearby shallows. We were told that occasionally a mother and calf will enter the harbor, which always brings about excitement on shore.

On one of our forays ashore, a chance meeting with a local farmer and his wife while we stumbled about in the bush trying to find a trail we had been told about resulted in the formation of a great friendship. The remaining days we visited the various villages, and our new farmer friends took us on two hikes to the top of the mountain on Niuatoputapu. The view from this peak offered excellent vistas of the island, the harbor and the nearby mountain on Tafahi to the northeast. On our second hike to the summit, while overlooking the 360-degree view, we witnessed six pods of humpback whales breaching and cruising along the shorelines.

If the weather is settled, you can arrange to catch a ride over to nearby Tafahi Island in one of the islanders’ open powerboats and attempt to climb Piu-‘o-Tafahi. The trail on this nearly 2,000-foot peak offers a fairly challenging hike to the top of the often cloud-enshrouded summit. If you’re lucky and pick a clear day, you should be able to get a photo of nearby Niuatoputapu with your boat nestled within the protecting arms of her barrier reefs just 5 short nautical miles away. The sparkling white beaches and brilliant turquoise water of the lagoon and reefs contrast vividly with the indigo blue of the deeper ocean beyond. It is a breathtaking sight when viewed from the heights.

There is virtually zero tourism in the Niuas. The only visitors who arrive there are from yachts, and yet this occurs so seldom that no organized tours, activities or events have been created. If you want to learn about any special places, see some part of the island, experience island life or visit one of the archaeological sites, you must introduce yourself to the locals and share in village life. Only then will someone likely come forward to offer you help on your mission. The tourism director for the Niuas has been trying to create some basic activities aimed at welcoming cruisers, but beyond a drive around the island’s perimeter, a cookout at one of the villages or the hike to the top of the mountain on nearby Tafahi, you’re pretty much on your own when it comes to entertainment. Some people might get bored quickly on this island where the pace of life is so slow and easy, but we loved it. We spoke to some of the local teenage boys, and they mentioned the existence of caves that contain the remains of ancestors, and yet when I tried to find an adult guide to take us there, mysteriously, no one seemed to remember where they were or if such things even existed. Interesting stone monuments have been excavated on Niuatoputapu. Some of these are quite large, and some appear to be astronomically oriented. No one I spoke with knew of their actual use or significance, and many of the locals have not even visited these sites.

If during your Pacific voyaging you wish to experience a bit of authentic South Seas culture that has not yet been spoiled or tainted by tourism — and where there seem to be more pigs, chickens and dogs than people — plan a stop in the Niua group of northern Tonga. Bring a few simple trading items and some small gifts for the children, and be prepared to be welcomed into a community that seems to have so little to share materially but has an endless capacity for warm and friendly relations with voyagers from faraway places.

Todd Duff and Gayle Suhich are back in the Caribbean, living aboard and actively working toward their next long-term sailing adventure.