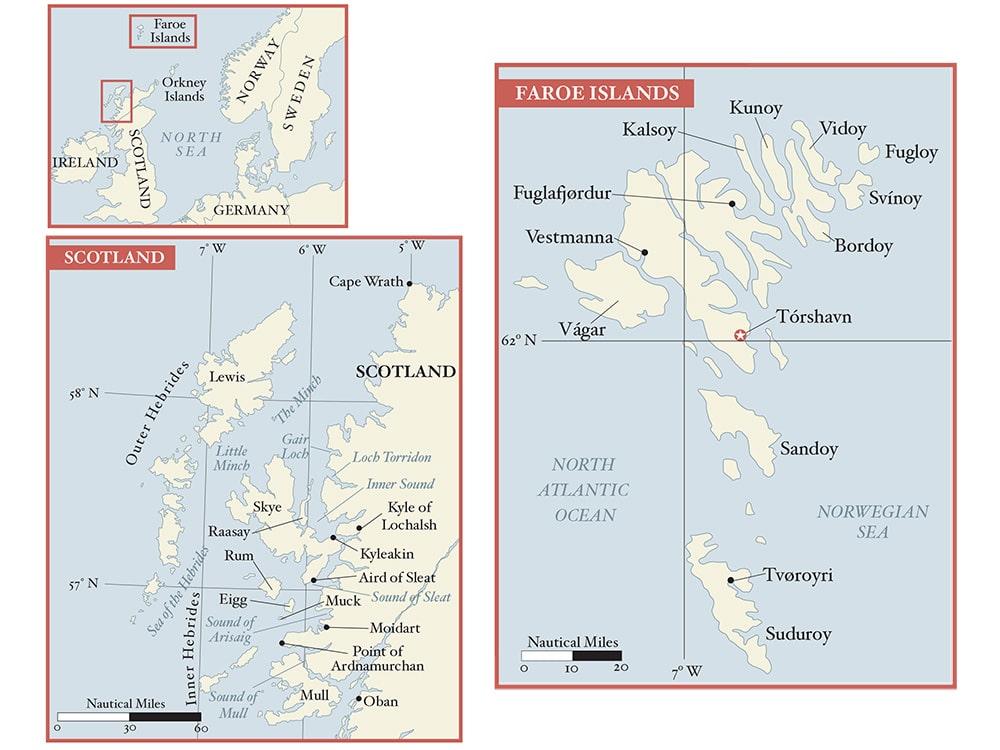

Aboard the 60-foot cutter Hummingbird, we’d set off from the enchanting waters of Scotland some 40 hours earlier for the approximately 240-nautical-mile passage north to the remote Faroe Islands. With a fitful southerly breeze, we’d knocked off much of the trip under sail alone, though we relented in the truly light stuff and kicked over the auxiliary to make some miles while motorsailing. All was going according to plan right up to our final approach to the islands, when damp, dense fog enveloped us and our surroundings. We knew we were literally right on top of the stark, dramatic Faroes, but we couldn’t see squat.

Hunched over the radar screen, we had a clear rendering of the pass we were aiming for when the fog magically lifted and the island ahead was almost instantly revealed. The sudden scenery was otherworldly, and the sense of accomplishment over tackling the longest leg of our journey northward — with a group of happy sailors I’d never met a week earlier — was palpable. Ahead lay new adventures in what is truly a remote, one-of-a-kind archipelago, but I’m getting ahead of myself. Our unique, thoroughly enjoyable cruise had originally commenced from a picturesque Scottish town hard by the sea.

Aside from a friendly Glasgow cabdriver, whose accent I unfortunately found completely incomprehensible, the very first Scotsman I spoke with, at the Kerrera Marina in Oban, offered this sage information: “There are three types of weather in Scotland,” he said, as I yanked up my hood against an annoying drizzle. “It’s about to rain, it’s raining or it just stopped.”

Well.

Moments later, I was tossing my sea bag aboard my home for the next fortnight, the 60-foot cutter Hummingbird (it was easily identifiable by the graphic depiction of its namesake splashed across its topsides). The sturdy yacht had some miles under her keel, having completed three circumnavigations in the Clipper Round-the-World Yacht Race, for which she was originally built. These days, the boat is one of two vessels owned and run by a company called Rubicon 3, which offers expedition-style trips focused on adventure and instruction all over the blue Atlantic (see “The Rubicon Experience,” at the end of the article). The skipper for our trip, from the northwest coast of Scotland and on to the distant Faroe Islands, was one of the firm’s founders, the young but remarkably skillful Rachael Sprot, who was ably assisted by first mate Holly Vint.

I’d already met Hugo, one of my shipmates for the trip, who somehow picked me out of the crowd at the Glasgow railway station (my foul-weather gear was apparently a dead giveaway) before we boarded our train to Oban. Soon after arriving, I was introduced to the rest of the crew, whose names I busily scribbled in my notebook for future reference. Paul and Sharon and Al and Nikki were the couples aboard, while Erika, Tanya, Hugo and I rounded out the contingent. With the exception of yours truly, everyone hailed from the U.K. — the pay-for-a-berth model on voyages like this is a decidedly British way to travel — and despite the fact that you need no experience on a Rubicon cruise (they’ll happily teach you all you need to know once underway), as I was soon to learn, everyone in our group was a solid sailor. And several were a testimony to the Rubicon experience, having already taken one or more trips aboard Hummingbird to diverse locations including Morocco and across the North Sea.

Our journey began with a leg from Oban to Tobermory, on the northern flank of the island of Mull, via the open waters of the Firth of Lorne and up a corridor of a channel called the Sound of Mull. The long-term forecast was rather iffy, but the sailing on this day was ideal, with flat water, a following southerly breeze and the sun occasionally poking through the clouds. And the scenery was out of this world.

If the picturesque town of Tobermory looked like something out of central casting, that’s because it is: The popular British TV show Balamory is filmed there. The quaint harbor and village looked almost fictional, with colorful buildings lining the waterfront.

Ferries zipped to and fro. A trio of Drascombe Luggers passed close by, hard on the breeze, looking like something from another era. There were rolling hills, a patchwork of greens, dotted with sheep. The farther we sailed, the prettier it got, with wooded headlands and dramatic cliffs, a castle here and multiple lighthouses there. The surroundings alone were amazing, but the sheer variety of sights made it special. Al summed it up perfectly: “This is Scotland at its very best.”

We gobbled up the 25 miles from Oban perhaps too quickly, but if the picturesque town of Tobermory looked like something out of central casting, that’s because it is: The popular British children’s TV show Balamory is filmed there. The quaint harbor and village almost looked fictional, with colorful buildings lining the waterfront, fishing boats tied to the quay and twin-keelers drying out at low tide. It was easy to imagine this as a spot where wee lads and lassies could grow and prosper. That night, we dined on local sea scallops (which were delicious) at a place called the Mishnish, an iconic Scottish bar with a name so cool I couldn’t stop repeating it. Mishnish. And before setting out the next morning, a few of us paid a requisite tour to the Tobermory Distillery, where I purchased a 10-year-old bottle of single-malt scotch for the boat, but which I wound up polishing off mostly by myself.

The anchorage at Loch Moidart was spectacular, ringed by white-sand beaches punctuated by the ruins of an ancient, formidable castle overlooking the loch. Whoever once inhabited it certainly held the higher ground.

Our next destination was another 30 miles along the track, to a nestled little crook in the coast called Loch Moidart. We first had to round the westernmost headland in the United Kingdom, a promontory called the Point of Ardnamurchan, identifiable by a towering lighthouse. (In days past, it was customary for ships returning from extended voyages to display a cluster of heather from their bowsprits as a token of rounding this exposed, dangerous cape.) From there, we jibed down the vast but mostly deserted Sound of Arisaig, where our only neighbors were three other sailboats and a minke whale. Compared to the previous day’s visual delights, this stretch of coastline was stark and austere.

Each day aboard Hummingbird, the duties of navigation and cooking (that night, Hugo and I prepared a chicken curry, my first) are assigned to different crew, and Paul and Erika had the mission of piloting this leg and into Loch Moidart, the entrance to which was a very tricky piece of water. The narrow channel was rocky and intricate — certain parts of Maine sprung to mind — with relatively deep water in the navigable bits but not a single buoy or marker in sight. Paul had rendered an amazing hand-drawn chart that noted all the twists and turns, and did a fine job of threading the needle among a labyrinth of reverse doglegs and a series of small isles. That said, just for good measure, a couple of crew kept a close eye on the Navionics app on their smartphones as we wound our way into the anchorage, labeled on the chart as Eilean Shona.

And what an anchorage it was, fully protected with white-sand beaches and punctuated by the ruins of an ancient, formidable castle overlooking the loch. Whoever once occupied it most definitely held the higher ground. After dinner, Hugo, Rachael and I hopped in the dinghy and went ashore to have a look, an outing that left me feeling like a cast member of Game of Thrones.

Our tentative plan at the outset of the cruise was to sail from the Inner Hebrides to the Outer Hebrides, but with the continuing flow of stiff southeasterlies, we had to abandon that idea because it would have placed us squarely on lee shores. Instead, we decided to make the short hop to the so-called Small Isles of Canna, Rum, Eigg and Muck, all of which I also enjoyed saying, particularly Muck. Each of the Small Isles was inhabited by a small community, and all of them had their own unique character.

It was pouring buckets as we left the loch (the rain is known as “Scottish sunshine”) and made our way across the Sound of Arisaig for a lunch stop off Eigg, where one can hear the “singing sands” on the beach when the wind and weather are properly aligned (alas, on this day, they weren’t). Muck and Eigg looked like Mutt and Jeff, the former a low-lying islet with nary a noticeable feature (except for a wind farm), and the latter a rather more impressive presence with craggy peaks and grazing sheep (and yet another wind farm).

From there it was on to Rum — owned by the Scottish Natural Heritage and home to both red deer and white-tailed sea eagles — which was a bit of a revelation, a monument to tourism on a very small, reasonable scale, with showers, a bunkhouse, a few rustic rental cottages, a post office and even a community center. We wandered along the nature trails with a stop at Kinloch Castle, an Edwardian mansion supposedly run as a seasonal hostel (though it was deserted at the time of our visit) that sort of seemed like a Scottish version of the Overlook Hotel of The Shining fame. Once we’d had a good look at Rum, we retired to Hummingbird for tots of, you know, rum.

From Rum, we had a decision to make: continue our tour of the Scottish coastline or press on directly for the Faroe Islands. Rachael had been closely monitoring the weather, where high pressure to the north of the U.K. had been fending off lows, as she put it, “sort of lurking off to the west.” A front was forecast to roll through in the next several days that would bring strong northerly winds, the direction we were headed. But in the meantime, it appeared that a favorable window had opened up. “Maybe we shouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth,” said Rachael. It was on to the Faroes.

As we approached the Aird of Sleat, at the southernmost tip of the island of Skye, the sky above was low and ominous (we were sailing into the “mist-ic”), and it was windy: We tucked in the first reef, then the second, and were still making 9 knots. Into the Sound of Sleat we went, where seals played in the whirling eddies and steep forests stood proudly to port and starboard. Soon enough, we were passing under the Skye Bridge that connects Kyle of Lochalsh, on the mainland, to Kyleakin, on Skye. Next stop: the Faroes.

As luck would have it, my turn to navigate had come up, a duty I shared with Nikki. Together, we checked off the landmarks as we continued north: first the island of Raasay and into the Inner Sound; then past Loch Torridon and Gair Loch, two bailout points had the weather turned, which it hadn’t; and into the broad seaway known as the Minch, with Lewis Island to port. For the first several hours, the wind was light and astern, so we motorsailed under a fingernail of a moon hovering over Cape Wrath at the northern tip of Scotland, which we soon put astern.

In the wee hours, the breeze filled in and we broad-reached at 8 knots under a full main and Yankee. It never did get totally dark, but still, at dawn, bright-red stripes to the east signaled the impending sunrise, and by midmorning, the sun was shining bright. (“We’ve turned around and are headed toward the Azores,” said Erika, kiddingly, when I awoke after a brief nap.) And that is how we carried on to the Faroes, sailing and motorsailing in about equal measure. Given our latitude, having crossed the 60th parallel, it was a remarkably easy trip. But we knew we were lucky. As Hugo said, “That could’ve been shocking.”

Our landfall was the island of Suduroy, which was shrouded in vapor and cloud, save for a sliver of blue sky to the west. The mist soon lifted, at least partially, and revealed our first glimpse of the place. I got the impression that this constituted a bright, sunny day in the Faroes.

Suduroy is the southernmost isle in the archipelago, a slab-sided hunk of land indented with deep fjords, with the town of Tvøroyri, the nation’s third largest, carved out of a fissure on the east coast. As we made our way into the port, we were greeted by big waves from the captains of the fishing boats headed out. After tying up alongside a historic trawler under reconstruction, the harbormaster turned up with offers of free showers and plenty of local knowledge. There might be friendlier people in the world than those of the Faroes, but I have yet to meet them.

From a cruising couple who’d spent time in the Faroes, we soon got an overview of the local customs. Those who visit the islands have traveled so far that they are greatly appreciated by the islanders. These days, there are roads and tunnels throughout the chain, linking the small settlements, but not long ago, people would think nothing of making a 10-mile walk to visit their “neighbors.” The spirit of hospitality is strong. During festivals and holidays, because there are so few pubs, if people leave a light on in their homes, it means it is open and ready for visitors. People greet you with a shot of schnapps, and the liquor and beer are flowing.

It’s a singing culture, and when folks gather, it becomes a festival of song. The traditional local fare consists of whale blubber, usually on the table with platters of small potatoes. The parties rage all night long, nonstop, until 6 or 7 in the morning. The sense of community is deep-seated. If only everywhere was the Faroe Islands.

We were eager to take it all in and the next day left Tvøroyri, bound for the northern island group, which we basically planned to circumnavigate. It turned out to be a slog. We’d been collectively stunned when looking at the local tide charts, where currents can and do run up to 8 knots, making timing through the passes a necessity. Heading north, it took us the better part of five hours to take a 15-mile bite out of our 75-mile journey, and what seemed like ages to pass the island of Sandoy. Plus, the fog had again closed in, rendering visibility to just about nil. Ahead lay a cluster of islands called Bordoy, Kunoy, Svinoy, Vinoy and Fugloy. But all I could think was, Oh boy, I can’t see a bloody thing. Eventually, we hoisted the spinnaker and ultimately escaped the grip of the rushing current. Finally, less than a mile from the pass we were aiming for, the veil lifted. Sort of. You couldn’t see the tops of the tall peaks, but you could easily take in the steep masses, the cuts in between. And they were spectacular.

We finally made it to the night’s anchorage in a deep fjord on the island of Vinoy. We dropped the hook inside a natural amphitheater of green cliffs, rushing waterfalls and striated rock. In my notebook I managed two words: “unreal” and “stunning.” It more than made up for the day’s travails.

The next morning found us en route to the mouthful of a town called Fuglafjørdur. Along the way, we negotiated the northernmost point of our journey at 62 degrees 18 minutes. The size and scale of everything is difficult to describe. Basically, these are islands where goliaths could come and play.

Along the way, tiny settlements appeared in the most unlikely places: on headlands, in valleys, clinging to the sides of precipitous mountains. It brought to mind unanswerable questions. Who inhabits these little burgs? How did they get here? What do they do? What happens if you get into a serious beef with your neighbor? Pretend you live elsewhere? The whole thing left me mystified.

As it turned out, we arrived in the fish-processing town of Fuglafjørdur on the occasion of a national holiday, and the tiny village was basically closed. We enjoyed dinner on the boat and the following morning set forth for another little Faroes town called Vestmanna. It was yet another jaw-dropping day of incredible beauty. Sheer sea cliffs plunged from great heights into the ocean. We passed a famous rock formation called the Giant and the Hag, a pair of sea stacks steeped in legend. Supposedly, the Giant and the Hag were dispatched from Iceland to drag the Faroes north, but no matter how hard they tried, the islands wouldn’t move. When the sun rose, they were transformed into rocks, which is how they exist to this very day.

After a quiet night in Vestmanna, it was time to make the final leg of the trip to the capital city of Tórshavn, a 25-mile jaunt through a series of canals, the highlight of which was recording a top speed of 14.1 knots thanks to the sweep of a mighty current. It was a fitting end to an eventful cruise.

After our tour of the rather far-flung islands, Tórshavn seemed like a bustling metropolis, even though it’s one of the world’s smallest capitals, home to about a third of the Faroese population of roughly 50,000. Still, it was a charming place, with a busy harbor, tidy shops, colorful buildings and quaint homes adorned with turf roofs, all circled by a ring of moorland hills. Before leaving, with cruisers Ginger and Dick Stevenson as my guides, I did as most Faroe residents do on a regular basis and took a long hike into the craggy trails above the city.

Still, at the end of the day, it’s the citizens of both Scotland and the Faroes that I’ll probably remember most. Yes, as we learned, both places can be wet, damp and cold. But the people? They couldn’t be warmer.

Herb McCormick is CW’s executive editor.

The Rubicon Experience

Rubicon 3, the company behind our voyage, has two oceangoing yachts, a 60-foot cutter, Hummingbird, and a Bowman 57, Oriole. Their itineraries span the width and breadth of the Atlantic, from the Caribbean Sea to above the Arctic Circle. Their trips cover a range of coastal adventures to offshore passages and ocean voyages, and en route one can receive hands-on instruction in celestial navigation, coastal cruising, seamanship and more. For more information on Rubicon’s entire range of sailing opportunities, visit its website.