The boy was the first Polynesian we laid eyes on. He was kayaking alone behind the jetty, in front of the village of Hanavave, his big brown body filling his sunset-colored craft. I waved and he waved back. Several aluminum skiffs were tied to the concrete quay where it seemed we should tie up our dinghy. There was no room for our dinghy. This was our first escape from Del Viento in 27 days.

We tied up instead to some large boulders adjacent to the quay, left a long painter, and scrambled ashore. We felt odd, foreign. The boy paddled over and began randomly pushing on our dinghy, maybe as if trying to move it. He was also speaking and shaking his head.

“We can’t park here, he wants us to move.” Windy said.

“How do you know?” The boy seemed to grunt and bark words at us and his expression seemed increasingly stern.

“I think that’s his Dad’s boat and we’re too close, the boats are going to hit. He’s not happy, we need to move.”

“How do you know that, I don’t understand a word.” Windy began flipping through our French-for-travelers book and I turned to Eleanor, “How do we ask if this is ok?”

“I don’t know.” Eleanor said. I felt a collective anxiety about the amount of French we’d failed to learn, despite attempts. We all suddenly felt fluent in Spanish and it was hard to keep those words in.

“Tray bee-en?” I called out meekly and anxiously; I didn’t want to move our dinghy and I couldn’t see a better spot for it.

The boy grunted and wagged his finger and shook his head.

“See?” Windy said.

A big woman appeared smiling next to us.

“Tray bee-en?” I asked her, pointing to our dinghy.

She smiled back, never diverting her eyes from us.

“Uh, tray bee-en?” I asked again, pointing again, nodding, raising my shoulders and lifting my brows theatrically.

She said something, her smile never leaving her face, and pulled a large, green citrus from her bag and pushed it at Windy.

“Ah, pamplemousse.” Windy said.

The woman echoed, “Pamplemousse…” and thrust the fruit towards Windy again.

Windy politely declined and the woman persisted until the hefty Polynesian grapefruit was in Windy’s hands. I watched the boy fall into the water exiting his kayak and then climb up the rocks to stand beside us.

“Eleanor, how do I ask how much?” Windy said.

“Uh, um, I don’t know Mom.”

“Lemme see.” I took the French-for-travelers book from Windy and began flipping through. It was nice to have a diversion. My eyes down and on the book, I was removed from the continued awkward attempts at communicating that Windy suffered. I could hear Windy was laughing too much; she does this when she’s uncomfortable.

I found it and I looked up to ask how much the fruit cost. The boy began jabbing at Windy’s shoulder, focused on her, like trying to get her attention. He was saying something, it sounded guttural.

“It’s twenty-five hundred francs, he’s saying the price of the grapefruit is twenty-five hundred francs.” Eleanor was hopping, giddy for her translation.

The woman smiled, looking down on the boy, shaking her head in a way that seemed she was amazed at how precious he was.

“That’s like $25 dollars, at least.” I said. Then I saw something in the boy. It was all clear in an instant. The boy was mentally disabled. The smiling woman, something was amiss there too.

Windy tried to offer the pamplemousse back to the woman, but she shook her head, pushing it harder into Windy’s chest. The boy continued tapping Windy’s shoulder, his insistent Polynesian or French words loud and assertive.

“Ok, au revoir! Merci! Merci beaucoup!” I called out while herding our small crew up towards the road. Windy held up the pamplemousse and offered final merci’s. The boy and the woman waved goodbye.

Then things went downhill.

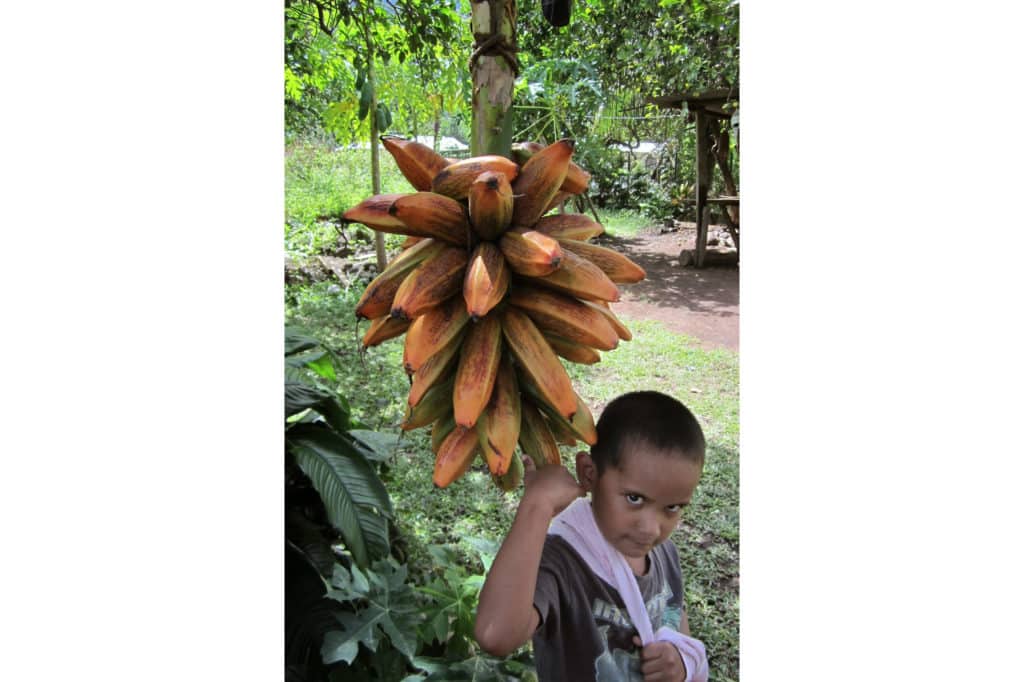

The encounter that followed was with a real pushy guy who wanted to sell us the fruit in his yard. We politely begged off, he continued to hawk. We were eager to get a sense of this new place and not comfortable with him. For 10 minutes we tried to extract ourselves, but without the words, yet our lingering probably seemed like interest. It was painfully awkward. “Merci, au revoir!”

Several houses up the street, we heard someone carving—with power tools—and went and stood by, hoping to capture his attention so that we could get closer and see what he was up to. Then Pushy Guy appeared next to us.

“Wood carving? You like wood carving?”

We nodded. He spoke a bit of English.

He turned and motioned us to follow. At his house, he urged us all in and we followed his lead, each of us removing our shoes before entering. His wife sat at a table inside with food all about. She swatted aimlessly at dozens of houseflies, her attention fixed on a soap opera dubbed in French. Pushy Guy steered us to a back room where several small carved tikis sat in a row.

“Iron wood, ebony, stone,” he said, pointing to each in turn. Then he did the same for a row of shallow bowls, “Iron wood, ebony, rose wood.”

We smiled and admired his work. I looked up from our book and said slowly, “Bonne, tres bonne.”

He showed us the prices of each. He proposed special prices for pairs purchased. We didn’t have the words to do anything but admire. I thumbed through our book, looking for later, looking for we’re just browsing now, looking for these things are beautiful and we don’t want to buy any just now, maybe never, but we thank you for showing them to us.

He extracted a promise that we would return tomorrow. He put a papaya into each of our girls’ hands. His wife turned away from the tube to see us off. She pulled a baguette off the table and thrust it at Windy.

“Merci,” Windy said, “Merci beaucoup.”

“Tomorrow? Tomorrow?”

Yes we all nodded, “Au revoir!”

We sat down on a riverbank where the girls swam.

“I don’t know about this place. I kind of want to flee. I mean, it’s unspeakably beautiful, but I’m not comfortable.” I said.

“We haven’t met that many people.”

“I know, but…”

The big smiling woman we met when we landed sat down next to us and again locked eyes, smiling.

“Smoke?” she asked, gesturing with two fingers at her lips.

“No, no smoke.” I pointed back and forth at Windy and me, shaking my head.

She smiled.

For 15 more minutes we sat with her, I tossed out questions I found in The Book, things like, Qu’est ce qu’on peut faire le soir? (What’s there to do in the evenings?) She rested her head on her hands to indicate sleep.

I managed to get her name, to find out where she lived, but it was like talking to someone…stoned…yes, that was it, she was stoned out of her mind. We were her entertainment, a diversion.

Something like 350 people live here, nestled under basalt spires in what is certainly among the most beautiful places on earth, the Bay of Virgins on Fatu Hiva, Marquesas, French Polynesia. In the dinghy and heading back to Del Viento, I wondered aloud whether I wanted to return to explore more tomorrow. I didn’t.

But I returned anyway.

I’m so glad I did. After Day 2, I like this place and its residents. But that story comes tomorrow.

In our twenties, we traded our boat for a house and our freedom for careers. In our thirties, we lived the American dream. In our forties, we woke and traded our house for a boat and our careers for freedom. And here we are. Click here to read more from the Log of Del Viento.