So, you’ve decided that you are sick and tired of hearing your boat’s diesel engine clattering away for hours on end while you’re recharging your batteries via your engine’s alternator.

You keep your boat on a mooring, so gaining access to shore power to run a dedicated 120-volt-battery charger isn’t normally an option. Solar panels or a wind generator could help, but you’re not too keen on the aesthetics or the reliability.

That leaves three options to satisfy your appetite for amps.

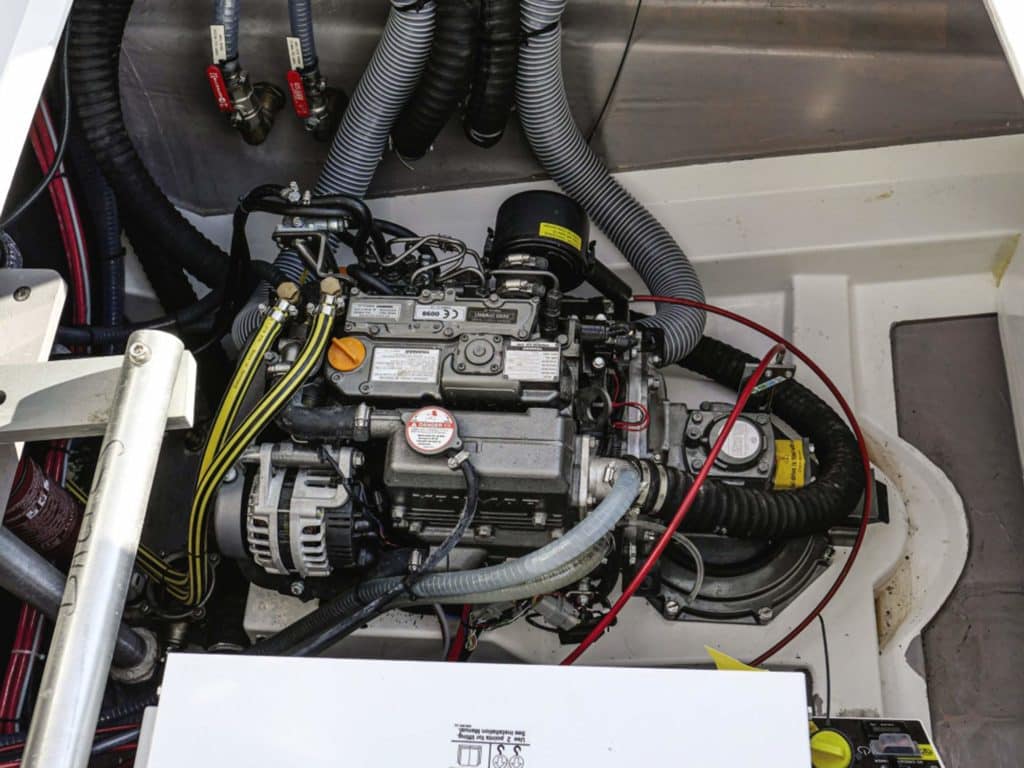

You could install an onboard AC generator, which will take up a considerable amount of space, is expensive, and will be just as noisy as running your main engine.

You could add an additional alternator that is dedicated to supplying your house battery bank, leaving the original alternator to service just your main-engine starting battery.

Or you can replace your original alternator with a high-output unit that can meet all your DC amperage needs.

I’m going to focus on those last two options, which are most likely to be your short list.

How hungry are you?

The first step in determining battery-charging needs is to perform an electrical-load analysis. You need to be brutally honest with yourself when you do this. Odds are that you are not going to be using all of your loads simultaneously. Many of your electrical loads will be considered intermittent. Conversely, many loads are going to be what technicians refer to as mission-critical.

The American Boat and Yacht Council, in its E-11 Standard covering AC and DC electrical systems on boats, provides a good guide for performing a meaningful load analysis. Examples of mission-critical loads include navigation lights and VHF radios. Examples of intermittent loads might be an anchor windlass, a horn or a potable water pump.

You can access the worksheet in ABYC E-11 by going to abycinc.org and clicking on “recreational boaters” at the top right. Then, click on “join ABYC.” Scroll down to the free five-day trial membership to access the E-11 appendix Table 1. Substitute your own electrical appliances for the ones shown, and fill in the current values. Add the columns, but for column B, take 10 percent or the largest load, which is usually an anchor windlass.

Going through this important step will reveal your appetite for amps. Keep in mind that this list is for DC appliances only. If your boat has an installed DC-to-AC inverter, consider it a DC load, and probably a large one at that.

Battery-recharge acceptance rate

Also consider the batteries you are attempting to recharge. All batteries have what we know as an acceptance rate. This means that no matter how much recharging capability you have, the batteries are going to accept only a percentage of that available electrical current (amperage).

Traditional flooded-cell batteries have an approximate acceptance rate of about 25 percent of charge. This means that if your existing alternator has a 100-amp output, your battery is going to accept only about 25 amps at a time.

AGM batteries have a higher acceptance rate. They come in at around 30 percent to 35 percent.

Lithium batteries have a much higher rate, but that is a story for another time; there is much to consider before you take that route.

The AGMs are my choice today because a higher recharge-acceptance rate means they can be recharged faster. And they can typically be discharged to a lower level without damaging the battery. These facts mean more amperage is actually available to run your equipment.

How about the alternator?

Once you have established your electrical-use habits, you can think about how much alternator power you actually need to meet your needs, and to dramatically reduce your main-engine run time.

No matter what you are told, trust me: This is not as simple as unbolting your existing alternator and bolting on a new, high-output unit.

Alternators consume some of your engine’s horsepower when they are working. How much? The answer varies depending on amperage rating, but about 1 hp for every 25 amps of electrical power is a good general rule. This is an important consideration if your auxiliary diesel has only 25 hp or 30 hp to begin with.

I share this information because one of the observations I’ve made in my many years as a CW Boat of the Year judge is that in every effort to meet price points for new boats, manufacturers will often slightly underpower them to save a few dollars in engine cost. We judge this by measuring boatspeed under power at various engine rpm. I learned this trick the hard way many years ago, when I installed a high-output alternator on a boat that had a one-cylinder Yanmar diesel engine as its main propulsion engine. The engine had about 7 hp. With the new high-output alternator, the boat couldn’t get out of its own way. It was a stupid and expensive mistake.

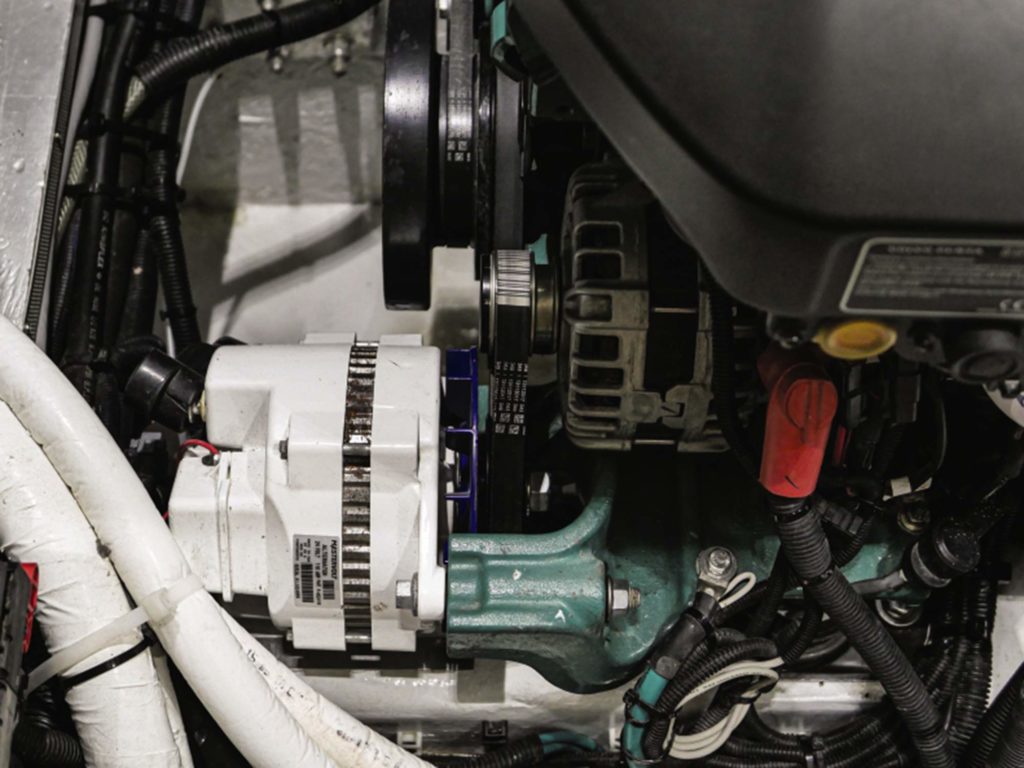

Another example: A 3GM30 Yanmar engine has a single V-belt drive for its standard 55-amp alternator. Let’s say that you need a 125-amp alternator to meet your needs. Well, you have gone beyond the threshold for the single-V-belt drive, which is generally considered to be 100 amps. This means you are going to need to replace all of the alternator drive pulleys on the front of the engine with either a double-V-belt set or a serpentine-belt set. This is a great upgrade and, in most cases, can be accommodated by installing one of Balmar’s AltMount serpentine-pulley conversion kits.

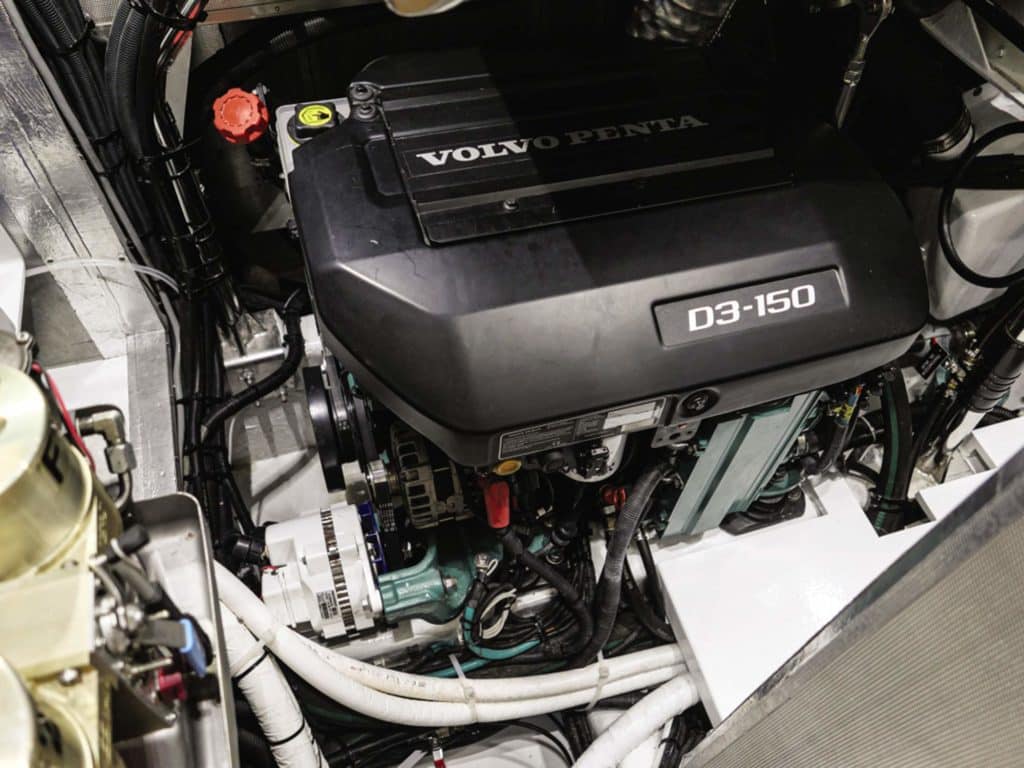

One thing we are seeing increasingly these days is dual-alternator installations. This setup is often configured as one alternator to recharge the engine start battery and a second for supplying house loads and recharging the house battery bank.

If you have space, this is a great way to go for a cruising boat because you have a spare alternator in case one fails. It won’t charge everything as quickly, but at least you will have a battery-charging source on board. Balmar offers second alternator kits.

What else?

Regardless of whether you go with one or two alternators to achieve your amperage needs, you’ll need to consider the mechanics of mounting these units to your engine. Is it a double- or single-foot mount? What about belt adjustment? Wiring and voltage regulation?

The tachometer for my original installation was driven by an electrical connection on the stock alternator. Does the new replacement have that same connection? If not, what about my engine tachometer?

If you are upping your amperage considerably, then you will definitely need to replace the wiring harness to your alternator.

And what about cooling? Alternators generate considerable heat, a primary cause of premature electrical-component failure. In extreme cases, thermal sensors are integrated with the voltage regulator to reduce output from the alternator when a certain temperature is reached. Considering that the larger high-output units cost more than $1,000, this monitoring and regulating is worth the added cost.

Using a matched external voltage regulator that is programmable is the only way to go, in my view. Considering the overall cost here, which may include new batteries, being able to program voltage regulation to maximize battery-cycle life is just common sense.

Is Balmar the only show in town?

No, although Balmar has done a great job of creating complete upgrade packages, and the company is a regular presence at boat shows. Several other sources are cruiserowaterandpower.com, boatid.com, dbelectrical.com and mastervolt.com.

Longtime Boat of the Year judge Ed Sherman writes frequently on a vast array of technical topics for CW.