Lyra 1

When my wife, Jen, and I bought our 44-foot Reliance ketch, Lyra, in 2008, we knew that most of the nearly 30-year-old boat’s systems would need updating. However, Lyra was in our price range and in good sailing condition. With the exception of our radar, the electronics and navigation equipment were large, old, and outdated. Last spring, having addressed other tasks, we could finally focus on our electronics. We had a tight budget to work with, so the latest-and-greatest giant, touch-screen, full-color multifunction displays were out. Our objective was to assemble a functional, modern navigation station that could do everything we needed yet not break the bank.

These are the instruments we feel are the bare minimum for successful cruising: a GPS, a depth sounder, a VHF radio, and an Automatic Identification System receiver. We decided to cover these bases and make provisions to add wind instruments, an SSB radio, a speed log, and an autopilot at a later date. For our purposes, we could choose between two options: an integrated multifunction display, or separate components integrated into a PC.

After doing some research, I discovered that a multifunction system that addressed our needs would cost about $4,000. At this price, we’d have a relatively small 9-inch display that would require between 3 amps and 6 amps of power draw. The upside to this approach would be the ability to integrate everything simply by plugging in components. Most new electronics use the NMEA 2000 communication protocol to share information, which transmits data more quickly than the older NMEA 0813 and allows the instruments to connect anywhere on the data bus, which can be a single cable running the length of the vessel.

The Standard Horizon GX2150 VHF radio (above) picks up A.I.S. signals with our existing antenna.

However, a PC with a 15-inch screen and a separate, component-based system would cost less than half that amount, and the system’s individual parts could be turned on and off as needed to save power. But this option would require a greater time commitment for installation, and it would use NMEA 0813 instead of the new NMEA 2000 communication protocols. The larger screen is nice, and we find that the use of a mouse and keyboard is a great way to maneuver around in the software.

Setting Parameters

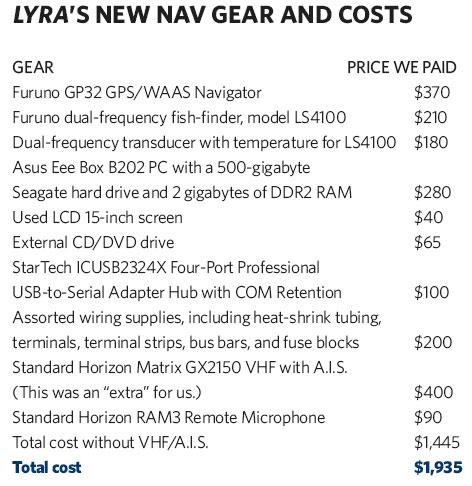

Because we had the time, and money was tight, we chose the second option and set a budget of $2,000. With the decision made, we set about designing the system.

Our priorities were straightforward: The total cost had to be $2,000 or less. We wanted rock-solid instruments with a reputation for dependability. We wanted to minimize any use of Lyra‘s battery power. We wanted the GPS data—course, speed, V.M.G., and more—to be repeated at the helm. And in the event of equipment failure, we wanted the other electronic gear to continue to function.

Our Furuno LS4100 fish- finder (above) helped us meet a major priority: to have course, speed, V.M.G. and more repeated at the helm.

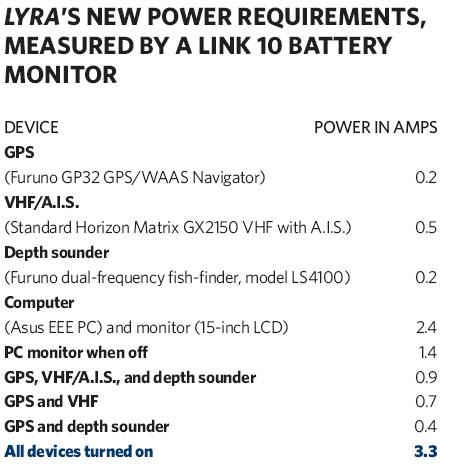

Lyra‘s battery capacity is 400 amp-hours, so we make every effort to minimize battery consumption. By switching pieces of the electronics suite on and off as needed, we’d also be able to dramatically reduce power consumption by using only the electronics required in any given situation. For example, making a night entrance would require all instruments, but on a nice evening 200 miles from shore, we might only require a steering waypoint and perhaps A.I.S. to help the watchkeeper monitor shipping. For that reason, we liked the idea of a multifunction data display at the helm, but because we prefer a dark cockpit that won’t impact night vision, we wished to avoid vivid colors and bright backlighting.

Ultimately, we chose a Furuno GP32 GPS/WAAS Navigator as our GPS unit, partly because of the company’s sterling reputation for production dependability and highly accurate instruments and also because this model, while not a chart plotter, has a very simple two-color display and provides the usual course, speed, V.M.G., waypoints, and so on.

Since my fishing skills are, well, limited, at first it seemed pointless to pay a few extra dollars for a fish-finder. However, a fish-finder will return a reading at far greater depths than most basic depth finders, which is nice for verifying bottom contours if the navigation software is off. Its dual-frequency transducer also can identify the consistency—mud, rock, or wreck—of the bottom, which is very handy for anchoring. As we didn’t need a color screen or a high-powered unit, we settled on the Furuno dual-frequency fish-finder, model LS4100. This unit will also repeat data, functioning as a multifunction display, and would mount at the steering console. Last but not least, when we decide to update our speed log, we can buy an NMEA 0813-compliant speed transducer and plug it directly into a Y-cable that’s supplied by Furuno.

Choosing the PC

Aboard Lyra, we like our computers, and we appreciate having the ability to upgrade, update, and multitask that comes with an onboard PC. Our nav-station PC would pull double duty as a second computer for general use. The challenge here was to keep power consumption and size to a minimum. Laptops are very good at conserving power, but we wanted a permanently mounted screen and a clear desk for log entries and chart work. Fortunately, several companies in recent years have integrated laptop technologies into desktop-PC formats. The Asus Eee Box B202 PC measures just 8.5 by 1 by 7 inches and can be mounted in a variety of orientations. It uses the same hardware as the Asus Eee Laptops, which makes it both small› and very power efficient; its 110-volt power pack can be snipped on the 12-volt output side and hardwired to the ship’s power.

Wiring everything together (above) was the project’s most challenging task.

PCMall.com was very helpful in assisting me to build an Asus Eee Box B202 PC with a 500-gigabyte Seagate hard drive and 2 gigabytes of DDR2 RAM. The processor is a dual-core Intel N270, which sips power at only 36 watts when wide open and provides adequate performance. The built-in WiFi even has an external-antenna connection that we’ll eventually connect to an omni-directional antenna on the mast. There’s no CD/DVD drive, so everything needs to be loaded via an external drive on one of the four USB ports or the SD card reader. To initially load the operating system or copy any files, such as charts, that are too large to email or download, we find that a 8-gigabyte SD card works well.

Sourcing the monitor was one of the project’s more difficult tasks. We wanted as large a screen as possible that would fit in our available space, which measured 15 inches from corner to corner, and it needed to run on 12 volts. The smallest screen that I could find new in stores had a diagonal measurement of 19 inches, and it ran only on 110 volts. Yes, there are many automobile monitors on the market, but they’re costly. We ultimately learned that many of the LCD flat-screen monitors built in the early 2000s had a 110-volt power supply with a 12-volt output that could be wired directly to the ship’s power by removing the 110-volt power pack. On Craigslist, we found a used 15-inch HP monitor for a whopping $40.

The last piece of the basic setup was integration. Getting the GPS, the depth sounder, and the other new instruments to talk to the PC and to each other was extremely time-consuming. Once each wire was cut to length, it needed to have a terminal end crimped on and soldered, and then have heat-shrink tubing applied. We also tested multiple configurations and communication each step of the way. If we had instruments that “spoke” NMEA 2000, this would’ve been much simpler to do.

And because we want to add more instruments to the mix later, we bought a StarTech ICUSB2324X Four-Port Professional USB-to-Serial Adapter Hub with COM Retention. This hub takes up to four separate DB9 connectors (9-pin serial connectors) transmitting either RS232 or NMEA data and condenses that data to one USB port on the computer, which frees up USB ports on the PC and resolves potential data conflicts. Jen and I eventually want to install an autopilot and wind instruments; each will connect into one of the DB9 ports on the StarTech for interfacing with the ASUS PC. If all we cared about was the GPS/computer interface, we could’ve purchased a simple serial-to-USB unit for less money.

Installation

Once we’d built the redesigned nav station, it was time to install and test the electronics. Each unit has NMEA input and outputs. I have to admit that my first reaction to the complex of wires and routing was unprintable. For example, here’s the wiring array just for the LS4100 depth sounder: Red (positive from battery), Black (negative from battery), Silver (wire shielding), Blue (transmit NMEA; A), White (transmit NMEA; B), Yellow (receive NMEA; A), and Green (receive NMEA; B).

In a system like this, there are two ways to move information, in series or in parallel. For example, in a series, or daisy-chain, installation, the NMEA OUT from the GPS might be connected to the NMEA IN on the fish-finder. The DB9 connector for the serial-to-USB adapter would then carry the NMEA OUT data from the depth sounder so that the PC would receive both the GPS and depth information. If we were interfacing to the PC with a simple serial-to-USB adapter, this would’ve been the best approach. However, in our example, the problem is that the PC won’t get GPS NMEA information if the depth sounder were to be turned off or broken.

In the parallel installation we utilized, the PC has the ability to receive and transmit data from up to four distinct inputs via the four-port serial-to-USB adapter. In our case, three separate instruments can pick up the GPS data output by physically connecting them together on a terminal strip. This allows the VHF, the PC, and the depth sounder to receive GPS data.

Once the GPS, the fish-finder, and the PC were all talking, it was time to add the VHF and the A.I.S. The Standard Horizon GX2150 VHF with A.I.S. is a rugged and intuitive submersible unit that used our existing VHF antenna to pick up A.I.S. signals being transmitted from vessels in our vicinity. Once it receives GPS input, it shows adjustable range rings with digital selective calling capability to each target on the screen. We also opted for the Standard Horizon RAM3 Remote Microphone for cockpit use, which displays the same information and also allows access to the radio functions. When it’s connected to the PC, we also get full A.I.S. targeting information on the chart program.

Following simple downloaded instructions, we installed Ubuntu, a free Linux operating system, and OpenCPN, an electronic-charting application that’s quite good. OpenCPN will run on a variety of operating systems and is also freeware. While it doesn’t yet have the slick interface and all of the bells and whistles of some of the established chart software, such as Expedition, it meets our requirements, including showing A.I.S. data on the charts.

Our only issue with OpenCPN is that it doesn’t support “Furuno talk,” so the GPS won’t accept routes uploaded from the PC. To address this, we export the route to a file on the PC, then upload it to the GPS using GPS Utility, another freeware software package. Raster charts can be downloaded at no cost directly from the NOAA website. If you’ve purchased vector charts, these also work.

The table below, “Lyra‘s New Power Requirements, Measured by a Link 10 Battery Monitor,” lists our very modest power requirements and a number of the configurations that we use to minimize onboard power consumption.

While we’re very satisfied that we inexpensively built a serviceable navigation system aboard our boat—it works flawlessly, we enjoy its easy operation and the ability to tweak power consumption, and we feel that the time spent sourcing and installing the system was worth it—we realize that our solution won’t work for everyone. But if you’re on a tight budget and can spend the time to research, troubleshoot, and install the gear, we believe that our approach represents a viable alternative.

Green Brett has been sailing and living aboard since childhood, and shares his love of cruising through his company, On Watch Sailing charters and instruction, based in Newport, Rhode Island.