Crowd Sourcing

A particularly weak aspect of most electronic charting so far is that the point of interest overlays that should help you conveniently plan cruising stops are often inaccurate. Heck, years ago someone conflated a private marina in my harbor with the town’s own transient-dock facilities, then several other digital-chart companies copied the error, and the resulting mess of confused VHF and phone calls continues to this day. It’s increasingly clear that no single chart manufacturer can keep up with even such critical marina details as phone numbers, let alone collect the wealth of information to which we’ve grown accustomed while web researching nonsailing trips from office or home. Professionally published cruising guides are also hard pressed to meet modern expectations for timeliness and detail, and they’re further challenged by our growing willingness to wade through online forums, blogs, and wikis for valuable opinions posted by fellow enthusiasts. Lastly, there are the problems our government and others are having with the collection and distribution of critical chart data, particularly for the remote areas in which we like to cruise. So the stage is set for boaters to share firsthand data like never before, and the tools to do it well are materializing at an astonishing pace.

You may already be acquainted with ActiveCaptain.com. Formed in 2007, it is an interactive website where members can add or edit finely detailed descriptions of marinas, anchorages, and the like while also posting personal reviews that are as frank as they wish. Nearly 100,000 boaters have registered so far—access and posting are entirely free—and I can attest that some harbors I know well are better covered in A.C. than in any other source I’ve seen. In fact, I’ve contributed to A.C. coverage along the Maine coast, and it feels good to share my local knowledge with fellow gunkholers. Founders Jeffrey and Karen Siegel are quite active cruisers themselves, though they somehow still manage to keep watch on A.C. data quality and to create new info-sharing possibilities like Hazard Marks, which A.C. members use to inform each other about such trouble areas as shoaling spots and misplaced nav aids. But the Siegels always hoped to see the data available beyond the confines of an online PC running a web browser, and now that’s happening in spades.

The latest versions of two premier PC navigation programs, Rose Point’s Coastal Explorer and MaxSea TimeZero, can quickly download and cache the entire ActiveCaptain database wherever the Internet is available, as can Navimatics’ Tides & Charts app for iPhones and iPads. I’ve had the gratification of editing an anchorage note or adding a hazard marker on the A.C. website and seeing the updates sync onto these applications’ charts in just a few hours. Several other companies that are developing nav programs for these platforms, as well as for Android mobile devices, are about to announce similar A.C. support, and even a couple of the big multifunction-display manufacturers are considering the idea. So you no longer have be online, or even sitting at a traditional PC, to benefit from A.C. resources, and all these data partners will eventually enable anytime A.C. input that will be synced back to the master database whenever you do get online. But that’s not the big news.

In October, Navionics announced that its Mobile 5.0 apps for Apple and Android devices will soon facilitate what it calls U.G.C., for user-generated content, and it’s central to a re-envisioning of the company’s whole product line. The “Navionics Anytime, Anywhere” program rolling out in 2011 will mean that along with the purchase of a chart card, a Navionics user will get access to the same charts via a variety of free mobile apps and/or a new PC program, all of which can be used to edit or view the “community layer” of user-entered data. Moreover, the U.G.C. entered on those apps that passes a Navionics validation process will become part of its central chart database, and these updates, along with conventional updates from official sources, will not only be immediately available to the online apps but can also be added to the original chart card and then used in your primary navigation device. It’s worth noting that Navionics founder Guiseppe Carnevali, who helped to invent electronic charting in the early 1980s, is the chief and enthusiastic visionary behind U.G.C.; it’s hard to imagine a more important endorsement of chart crowd sourcing.

Rounding out this whole Navionics ecosystem of online and offline user and pro data is a concept called Plotter Sync whereby a display made by, say, Raymarine—the first to demo it—and networked to a WiFi router automatically recognizes the Navionics app running on, say, the iPad on which you recently planned your next cruise and, bada bing, downloads the route. Now at this writing, the timing and details of all these features are a bit tentative, and Plotter Sync obviously involves partner cooperation, but note that once a mobile device-to-fixed boat system wireless connection has been created, further possibilities abound. For instance, the mobile device might receive vessel-sensor data like GPS, wind, and depth—thus making it better for backup navigation—and/or it might deliver collected-ashore online content like weather forecasts or software updates to the boat.

I digress, but a glimpse at the whole Navionics vision does suggest what a big deal U.G.C. is and the level of enthusiastic embrace that one hopes it will receive from manufacturers and cruisers alike. It also explains why the U.G.C. facility in Mobile 5.0, which I’ve been beta testing, includes extensive abilities to add or edit nav aids and other critical chart objects. For instance, it’s easy to drop the appropriate icon for the various privately maintained channel and hazard buoys that are often uncharted today. And if what you discover is a misplaced aid or rock or marina, the “community layer” of the Navionics app will show its original position as well as the new one, so other users can double check, and possibly correct, your chart edit. Note that everyone’s updates are automatically sent to all other Navionics apps that cover the same chart area, instantly if they’re online, and the community layer can be turned off if the chart gets too cluttered for other uses.

Some traditional navigators object vociferously to the idea of user-generated chart updates, but the truth is that official cartography organizations like NOAA seem hamstrung by cumbersome survey/update processes and limited funds. Besides, NOAA’s stated priority is commercial shipping areas, not remote cruising grounds. The tricky part for Navionics will be validating such updates, though some will be easy. For instance, there’s a harbor breakwater in Jonesport, Maine, that’s gone uncharted for over 20 years, though it’s clearly visible on easily accessible satellite-photo maps. Nearby and more problematical is a charted, but likely nonexistent, awash-at-low-tide rock that appears to block an otherwise attractive passage to beautiful Roque Island. Navionics may understandably balk at removing it altogether—the lawyers!—but even a charted note listing all the cruisers who couldn’t find it—including me, using side-scanning sonar equipment—could reduce the anxiety, or long detours, experienced by first-time visitors. I understand the reluctance of traditionalists—official charts have earned biblical status—but I like to think they’ll come around when benefits like the ones above become common.

The Navionics U.G.C. system provides less controversial point-of-interest data on marinas and anchorages too, though with less detail than ActiveCaptain and without A.C.’s rating/review capabilities. There certainly are other marine-oriented, user-generated databases available, as well as professional content formatted to take advantage of the web’s unlimited page space and rapid updating, and hardcore cruisers may find themselves looking for a program that supports as many sources as possible. Rose Point Navigation’s just-released Coastal Explorer 2011 offers a great model for what’s possible.

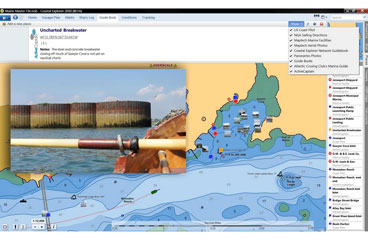

When C.E. 2011 is online, the Guide Book mode lets you overlay the chart of a possible destination or route with A.C. info, worldwide photos shared on Panoramio.com, official content parsed from pilot books and Sailing Directions by Rose Point itself, and even C.E.’s own form of crowd sourcing. The latter is more free form than A.C. or U.G.C., and while it hasn’t caught on yet in the United States, extensive piloting and even marine history for the United Kingdom and western Europe is freely downloadable in this form. All these layers can be switched on and off individually, and all disappear when you switch to another C.E. mode. This data also stays cached on your PC, and Rose Point has even devised an automated way to pass it from your laptop to a permanently installed boat computer.

MaxSea TimeZero charting software already offers some of the same data as C.E., has a similar architecture for handling it, and other developers are catching up. But Rose Point has also demonstrated how neatly traditional and still handy printed guides can be integrated into multi-source cruising-info systems. Its partnership with the Atlantic Cruising Club means that C.E. users can view marina extracts from the A.C.C.’s meticulous guides for free. And if a C.E. user buys one of the guides, the included CD will make its entire contents, plus extras like more photos, available in C.E., along with updates that are easily synced along with all the other sources mentioned.

Other professional publishers are certainly looking at ways to make their data more accessible and fresher using the same underlying technologies that make crowd sourcing possible. The Waterway Guides, for instance, are not only posting updates on its website but also making its printed products available as iPhone and iPad apps. Some of the data is also searchable on the new EarthNC Apple and Android charting app, as is info from Marinas.com, Marinalife, and CruisersNet.

Plus there’s a whole other aspect to marine crowd sourcing that I haven’t mentioned: straight up data collecting. Survice Engineering has just tested the Argus system in which volunteer vessels used their own electronics to collect depth and water-temp data into an Argus device able to store it for later WiFi transmission to Argus servers for quality control and, possibly, eventual submission to NOAA. If successful, future volunteers will get free high-power WiFi for their trouble, and NOAA’s survey backlog will shrink. A similar but more cruiser-to-cruiser project is under way in England.

Are you getting excited about user-generated content yet? I hope so, because I have a proposition: I’ll keep typing my Maine cruising discoveries into whatever crowd-sourcing formats I can (and writing more about the choices on my Panbo blog, available via www.cruisingworld.com), but I’ll also be looking for some quid pro quo from you next autumn. Gizmo, God willing, will migrate down the coast and, while I’ll certainly bring along a wealth of official cartography and professional guide content, I think I’ll have an easier time, and more fun, with further guidance from my crowd.

_

Ben Ellison is_ CW_’s electronics editor._