A dinghy is indispensable. It’s like the family car. It’ll take you shopping, to the chandlery, and to the bars and restaurants. Dinghies are good for exploring shallow creeks, visiting other cruisers, and running out to set a second anchor in the middle of the night when the wind pipes up. A dinghy can even save the day if the engine fails and you need to tow your big boat out of danger.

My first dinghy was a plywood pram, 6 feet long, powered by two oars. I towed that thing behind my 34-foot Alden Barnacle sloop, Quinta, for 10 years. I had to tow it because there was no room on deck to stow it. That dinghy came by its naughty name, Little Bastard, for its pesky behavior of always getting in the way when docking.

The next dinghy, for my 41-foot sloop Fare-thee-Well, was an 8-foot aluminum skiff. It was also manually powered, but it had chocks on the cabin top for stowage. It was a pain to hoist aboard, invert and lash down. It also obscured visibility.

A string of inflatables came next, and I found them much easier to deal with. The first was a blue Achillies 8-foot roll-up. Its sole was three pieces of marine plywood that I’d remove after deflating the pontoons. The whole thing rolled and stowed in a bag, secured to the deck forward on the mast. I had that dinghy for 10 years. It was fitted with a 10-hp, two-stroke outboard that was enough to push my Lord Nelson 41 sloop, Afaran, 5 miles up Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island to a marina to replace the seawater pump on the BMW diesel engine.

Two more RIB dinghies followed, both made by AB, each one 10.5 feet long, and each one fitted with a 15-hp Yamaha. This arrangement was sufficient to tow my kids on a wakeboard and push my Bowman 57-foot ketch when the diesel engine was, well, not working.

Options on the Market

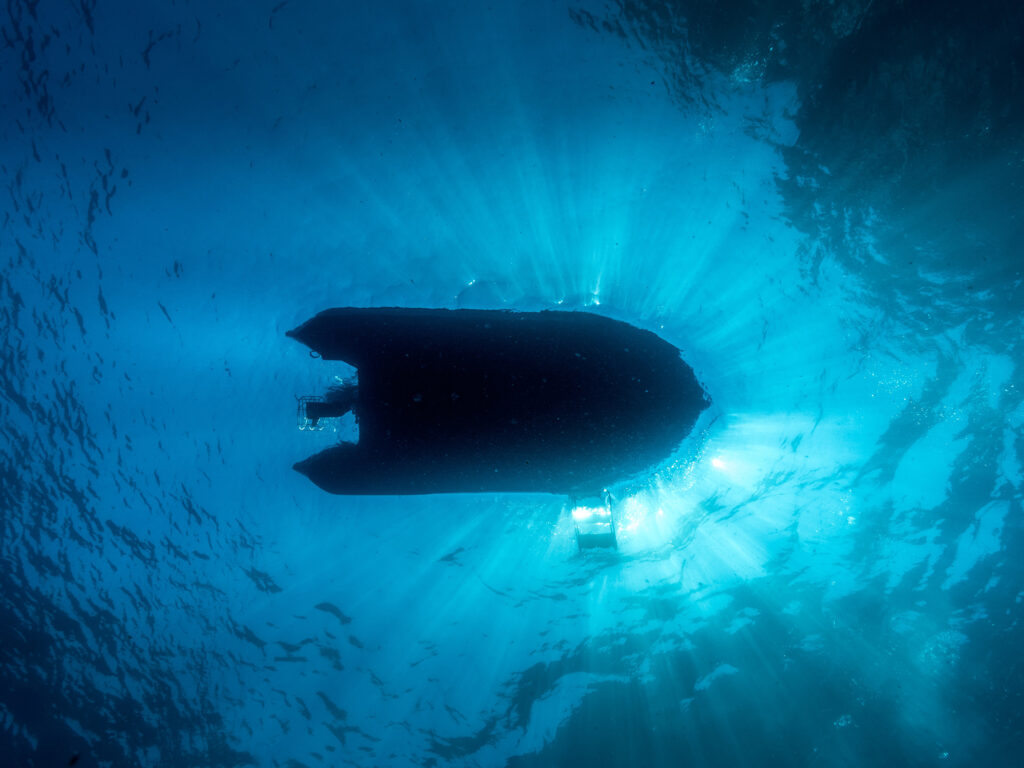

There are many types of dinghies available: lapstrake wooden peapods, traditional gigs, a plastic Portland Pudgy, an all-aluminum design, and a whole line of RIBs. They will all work, but the inflatables have advantages. They are more practical and are easier on the topside of the big boat. They can carry more gear and supplies, and they can go faster with a good-size outboard. They also are more stable, and if they’re swamped, they can still float.

I was at the Miami International Boat Show in February and spent an hour in the inflatables section. There were multiple manufacturers to choose among, including Achilles, AB, Highfield and Zodiac. One model was a newer version of the 10.5-foot AB dinghies I’ve owned for 30 years, but with the option of an aluminum hull and a larger bow locker to accommodate the gas tank, with the hose run through the double hull to the stern. Nice and neat.

True Kit USA showcased roll-up inflatable boats from 7 to 11.5 feet long, each with a catamaran hull design. The boat rides on the pontoons, and the sole is above the water. The weight of these dinghies impressed me. The Discovery 330—at 10 feet, 10 inches long with a 5.5-foot beam—weighs in at 88 pounds and has a price tag of $2,100. It can accommodate a 1-hp engine and carry four adults. With an aluminum transom, the entire boat, including the bottom, can be deflated, rolled up and stowed on or below deck.

EZRaft, a Netherlands company, has a 10.5-foot inflatable roll-up model that weighs just 34 pounds and lists for $1,690. Availability right now is outside the United States.

GoDu has a line of inflatable-type boats made of aluminum with no fabric pontoons. The 10.5-foot model weighs in at 168 pounds with a $9,000 price tag. It’s another $1,400 for shipping within the United States.

Many of the RIBs I saw came with center consoles. Sure, it may be more fun to sit behind a steering wheel than on a pontoon, but a dinghy is for practical use—ferrying people, groceries, duffels, fuel and water tanks, and diving gear. I think these center-console dinghies are best for people doing things other than long-distance cruising.

Outboard Engines

No matter which dinghy you buy, my big advice about the outboard engine is to get one large enough to push your big boat out of trouble, into an anchorage or up to a dock.

Towing is not as efficient as a “hip tow,” which is when you lash the RIB to the starboard quarter of your big boat, with fore and aft lines, and secure the outboard’s tiller amidships. The outboard then provides the power, and you steer with the big boat’s helm. A RIB is also handy when you need help maneuvering your big boat into a narrow slip.

A 15-hp outboard was all we ever needed to get on a plane with four of us aboard. It was also sufficient power to tow the kids on a wakeboard or water skis. The 15-hp outboard also got us around harbors at a good clip, allowing the four of us to go off on long expeditions to distant beaches and hiking trails.

Dinghy Maintenance

RIB fabrics wear out as much from the sun’s ultraviolet rays as they do from use, so fitting fabric “chaps” may extend the useful life of a new dinghy. These chaps also look nice. West Marine sells them for around $900.

After a month or two in the Caribbean, a dinghy’s bottom may need a good cleaning. Yes, there is antifouling paint for inflatables, but it will wear off.

Another option is to take the dinghy ashore to a vacant beach, remove the engine and all the gear, drag the RIB up on the beach, and flip it over. Spray the bottom’s slime and growth with a mixture of bleach and water, and then scrape and scrub, rinsing frequently with buckets of seawater. The process usually takes less than an hour to complete.

Dinghy Stowage

We always towed our dinghy if we were motoring down the lee of bigger islands. But for scooting between islands, it’s better to haul the dinghy on deck. The trade winds and seas in the open ocean can play havoc with a towed dinghy.

My advice is to hoist the dinghy on deck and secure it, engine and all, forward of the mast. On long offshore voyages, stow it upside down with the engine removed.

Our Bowman 57, Searcher, had deck space abaft the mizzen mast to stow our 10.5 AB dinghy upright and covered. If your big boat is actually too small to accommodate a dinghy on deck, then a roll-up model is the answer. Another good option to consider in that category is the 3D Tender, which has models available in the islands of the French West Indies.

Dinghy Security

It’s important to haul your dinghy out of the water at night, even if it’s just up along the topsides, hoisted with a masthead halyard.

Ashore, usee a stout chain and keyed paddle lock to secure your dinghy to the dock. Don’t use a combination lock, which is impossible to see at night. At a beach, carry a small anchor, chain and rode to secure your dinghy’s stern.

Also, fit your dinghy with a tracker in case it goes adrift or is stolen. I recommend the LandAirSea 54 GPS Tracker. It’s the size of a hockey puck, costs $10 and will update its location every three minutes if you get a $20 monthly subscription. It does need to be within range of a cellphone tower, though, so it is unable to upload its location from far out at sea.

Last but not least, have backup plans. In addition to our well-used RIB, we also carried two kayaks and a windsurfing board. With these, the kids could go off exploring on their own—and we had another means to go ashore if we needed it.