From the top of Galeb‘s 50-foot mast I could see 9 miles to the horizon. With the Canaries 1,400 miles behind and Barbados 1,400 miles ahead of our Dufour Gib’Sea 43, I’d have to be quite a bit higher to see land.

I finished retying the jib halyard to the head of the raised sail and cut off the chaffed section. It took a while, as I groped at tools and knots between bear-hugging the pitching mast. I could feel bruises forming on my arms and legs. My muscles were at their limit, and I wondered if they could handle the next roll and keep me from swinging out on my harness and safety lines.

Don’t get me wrong. I wanted to climb the mast. Most of our crew did. It was one of those naive new-sailor adrenaline kicks, perhaps. When I awoke to talk of the spinnaker halyard wrapped around the top furling swivel, I popped out of bed eagerly, but disappointed to learn that Chris, one of our captains, was going up instead.

After we lowered him, however, he announced that the wrapped halyard had sawed at the jib halyard, which was now hanging on by a thread.

“We’ll either have to lower the jib, which will require unfurling it completely, or someone will have to go up again,” Chris said. A quick look at the 15-knot winds and 6-foot swells, and he turned to me with his East London lilt and asked, “How ’bout it, Michelle?”

I’d basically begged to climb the mast, but now I was begging to come down. I taped the end of the repaired halyard, gave it a quick pass with a lighter, fumbled the tools back in the bag, and called down to be lowered.

Chris, though, murmured something back.

“What?!” I yelled, annoyed for the delay.

“Can you see Steve?” he shouted.

Steve! Our obsession. He’s the Kiwi owner of Proxima Vida, a Dufour 455 that is Galeb‘s buddy boat, and Chris’ compadre. When Chris met Steve in Montenegro in July, Chris and Luci had been cruising on Galeb for four months, after having sold their house and motorcycle school in London. Chris, a chatterbox, got talking with Kev, Steve’s father. Turns out Steve and Chris were both leaving the next day for Corfu, so they set off together on a passage that became a partnership.

They followed each other through the Med, chatting on the VHF about squalls or plans or just anything that came to mind. When Steve ended up singlehanded, Chris and Luci stayed close, stalking him through binoculars, worrying like parents every time he disappeared for more than 10 minutes. “I was probably in the toilet, bro,” Steve would say.

As the two boats left the Canary Islands for the Caribbean, fully loaded with provisions and crews of hitchhikers, Steve broke the news that we probably wouldn’t see him again because his boat was a bit faster. He shot out ahead from Las Palmas, almost lost to the horizon — until we caught up and passed him. And then he passed us.

Staying with Steve became a priority. Each watch change, we’d pop our heads up, look around and inevitably say, “Where’s Steve?” Then we’d jump on the VHF, exchange coordinates and adjust speed and course to find each other. We were leapfrogging across the Atlantic in our very own rally.

Aboard Galeb, we cruised like a bunch of teenagers on a graduation trip. Luci, 31, and Chris, 48, were on an exodus from Brexit. The Polish engineers Arek, 27, and Łukasz, 28, friends since childhood, flipped their settled lives for adventure. Alice, 20, an adventurer from Quebec, was earning her sea miles. And then there was me, a 32-year-old perpetual traveler making a great circle back to the Caribbean after sailing to Europe in July.

The crossing was a cakewalk. Between us we had a decent amount of sailing experience, both coastal and bluewater. We were all eager, with much to learn from each other. We listened well and considered all suggestions, a level of democracy that is rare in the world.

With six of us, watches were two hours on, two hours standby and eight hours off. We took the helm a few times to get a feel for the boat, but our Raymarine ST6000 autopilot, Rosy, worked flawlessly and steered 98 percent of the time.

Over on Proxima Vida, its crew of four was battling a finicky autopilot that would shut off randomly, probably because of a poor electrical connection. They were spending their three-hour watches with an eye on the helm, and Steve was awake most of the time with an ear to his boat. But at least their watermaker was working.

I wanted to climb the mast. Most of our crew did. It was one of those naive new-sailor adrenaline kicks, perhaps.

When we set off from Las Palmas with a newly installed watermaker, 570 watts of solar panels and 600 amp-hours of batteries, we felt confidently prepared for self-sustainability. But you can’t prepare for everything. Despite clear, starry nights, clouds seemed to puff up daily with the rising sun. And after just two days, the brand-new desalinator stopped making fresh water and started making bilge water.

Arek and Chris spent most days with their heads buried in the watermaker compartment. They tightened bolts, repaired ripped gaskets, dismantled, rebuilt, added glue, and when all that didn’t work, they offered it gifts: money, candy, alcohol, affection. After a week, they sat with a rum bottle nestled against the machine and their heads in their hands.

“Right,” said Chris. “If it works, we drink. If it doesn’t work — we drink.” And that’s how our midocean watermaker-fixing party began. Never mind that the watermaker was not fixed, and still isn’t.

We started with a sunset singalong to Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Daylight faded into colored LED cockpit lights, and we cruised under winged sails. We crept up close to Proxima Vida and passed it to port, casting our dancing shadows on the sails with flashlights and taunting them with loud rock music. As it fell behind, a light suddenly spread across its mainsail. A crisp shadow climbed into the beam, one hand sprouting one single straight middle finger. We cheered and sailed on ahead.

The next celebration was Łukasz’ birthday, January 12. All morning we baked brownies and learned to sing happy birthday in Polish. When Łukasz woke for his watch and disappeared into the head, we huddled around the door, reciting the words in our heads, with candles lit and burning, and burning, and burning — down to their stubs. We should have realized that the first bathroom visit of the morning is usually the longest. When he finally stepped out sleepily, we bombarded him with out-of-tune singing and birthday cheer.

The day before, we had caught our first two fish, a pair of meter-long mahimahi. We still had two mangoes that weren’t lost to the sea when our stern fruit net ripped. So I set to work breading and frying fish, and mixing up a mango salsa for tacos. Chris stood watch, eating with the sunset, and we all nestled around the table down below. Just then, the boat rolled, the jib backed and a loud bang rang out. The kind of bang you know is not a whipping sail or a slapping block. Our eyes popped and Chris yelled from above, “The pole broke!”

By the time I turned off the burners and climbed above, the jib was already furled and the aluminum whisker pole was resting on the deck, bent perfectly in the middle.

Chris and Luci had ordered a 5.3-meter pole in Palma de Mallorca, receiving instead one that was 6.3 meters long. “Well, bigger is better, right?” they reasoned. Or maybe not, as we’re thinking the extra length was too much for the 80 mm-diameter aluminum.

We tossed around repair ideas and the next day finally decided to saw off a meter of the pole for an internal splint. Because of the break, the pole was now warped in the middle, where the working force would be greatest. The outer ends were still straight though, so we drilled off the end fittings and cut our repair piece.

To fit in the splint, we needed to make the tube a couple of millimeters narrower. Arek meticulously marked two parallel lines, and we took turns wrangling loose hacksaw blades and grunting and sweating to saw out the strip of aluminum. Jokes and beers were cracked liberally. We squeezed the splint with hose clamps, hammered it into the pole ends and riveted it in place. A perfect fit and a fine day’s work. We were setting our new, improved, shortened pole as the sun set.

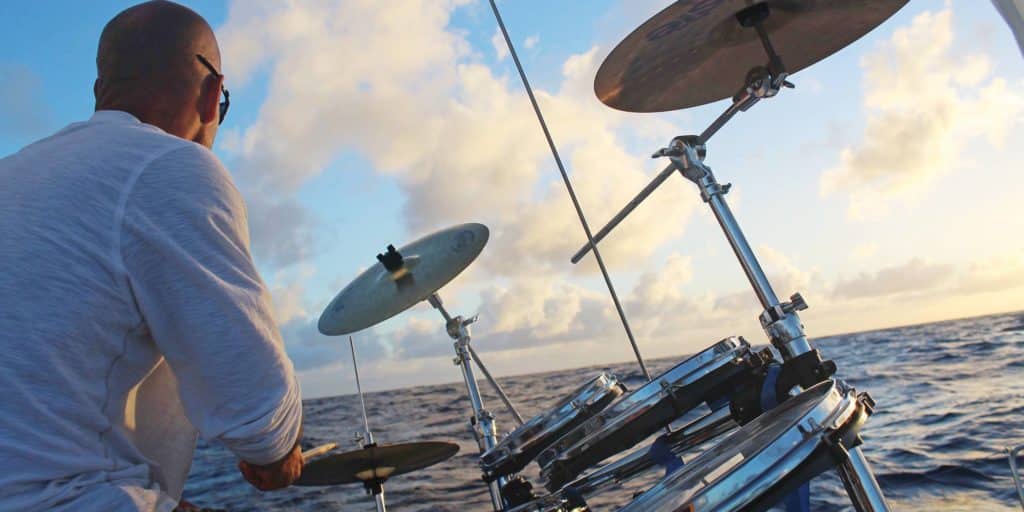

If there wasn’t something to fix, we had to get creative with our adventures. Like the day we swung the bosun’s chair out on the boom to bob and bang in the swells. There were cockpit jam sessions. The boat was stuffed with two acoustic guitars, a banjo, a ukulele and a drum kit. Drums on a boat? Chris, the drummer, reasoned, “I’ve always wanted to play the drums on some deserted island, you know?”

And there was the asymmetrical cruising chute, which Chris was dying to fly. The thing was, our reliable trade winds barely dropped below 15 knots, which felt like borderline kite-flying conditions, especially with the 6-foot swells. Without a sock, dropping the sail would have to be well-planned. We waited for a light-wind afternoon and hoisted the spinnaker. The halyard creaked and groaned, but it flew well, and we managed to quickly wrangle it down through the front hatch as a wall of gray squall sprang up behind us.

The next day was for mast climbing and chaffed-halyard sorting. And the next was for running the chute a second time. Again it complained going up, with two of us cranking the winch to keep the foot out of the water. But once it was fluttering full, we settled into some nice downwind sailing. Until, that is, the halyard snapped with a loud pop, and the chute shimmered gracefully into the water. The crew sprung into action, pulling the soggy sail out of the water within a minute.

So that was also the day that three more people went up the mast, each attempting to feed the snapped halyard back through the mast with a weighted string. The line looked as though it had stretched at the core, rather than chaffed. Just too weak, perhaps? We replaced it with the sturdier topping lift line and reset the winged jib and mainsail.

Fishing was a constant endeavor, but beyond the pair of mahimahi, we didn’t have much success. We hauled in one mystery species we were afraid to eat, a baby mahi we couldn’t release because the hook had ripped its jaw, and a slew of flying fish, some of which slam-dunked into open hatches and hid in the cabin until we smelled them. One was under the saloon table a few days, and another landed in a shoe in the V-berth.

Steve, on the other hand, had a freezer loaded with fish. He’d call out on the VHF, “Caught another mahi today!” or, “Hey bro, want a tuna?”

We refused at first on pride, but then on practicality. How would we manage to get a fish from one boat to the other? We seemed so close, but the distance between us was deceptively insurmountable. That is, until we executed our first boat-to-boat transfer: the egg drop.

Steve needed super glue; we had some. We stuck it in a big plastic Kinder toy egg and let it trail out on a long line. Steve motored up behind and snagged it with a boat hook. Success.

The fish shimmered down our port side, Łukasz dived at it with a boat hook, snagged it and pulled it up, cheering.

Which got us thinking. If we can do it with glue, why not with a fish? When Proxima Vida caught yet another mahi, we were at our wits’ end with our stores of seaweed and canned meat. Today we wanted something fresh — and maybe we were just a little bored too.

Steve stood on his swim platform, holding our dinner with a line tied around its tail. On Galeb, Luci held the helm, and we all stood on deck, boat hooks, cameras and portable VHF ready.

“One hundred meters,” crackled Proxima Vida as Steve let out the line. “One hundred fifteen, 130.”

“Can you see it?” yelled Luci. There was a glimmer in the water as the fish slid back while we motored toward the other boat.

“One fifty,” the end of the line, radioed Steve.

“Turn starboard!” cried Chris at the bow. The fish shimmered down our port side, Łukasz dived at it with a boat hook, snagged it and pulled it up, cheering. For just a second we were finally connected to our sistership. Chris quickly taped something to the line, cut it and sent it back.

“Hey Steve,” he called on the VHF. “Check the line, I left a present for you.”

“All right, more super glue!”

That night we ate mahimahi cooked in garlic butter, rice and coleslaw.

A week from Barbados, the weather finally shifted tropical, and the first hot days saw us shedding our sweaters and melting in the sun. I was dying for a swim or a tow behind the boat, but our steady winds and speed never faltered, so I settled for dunking my head in buckets of seawater.

The squalls transitioned to their tropical selves too, delivering the rain they’d been threatening. We scrambled out from the covered cockpit to dance and bathe in the downpour, delighting in free water as the watermaker struggled in the saloon.

On January 23, day 20, Barbados was 130 miles away. Proxima Vida was a little ahead. We would lose it in the night, and it would beat us to anchor in Port St. Charles, winning our long, slow race.

I escaped to read on the bow. I was tired, ready for a break and to sleep a whole night through. I was desperate for a quiet evening. But then, it was our last night at sea, and there was one shenanigan left to pull.

“Michelle,” said Chris, popping up through the forward hatch, eyes bright with excitement. “I have to move you. We’re going to set up the drum kit here.”

Michelle Davies is a freelance writer whose early years were split between rural life in Oregon and boat life in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently, she is still floating from adventure to adventure, balancing travel with writing, self-care and family time. Follow her adventures at knowinghome.blog.