Cruise for long enough and you’ll be faced with a situation where you’ll need to make a gasket for your propulsion engine, tender outboard, genset or other onboard gear. While it’s always best, and easiest, to use the manufacturer’s original equipment gaskets, these may no longer be available, or inaccessible if you are at sea or cruising in a remote location.

Several years ago, while cruising along Newfoundland, Canada’s south coast — where there are few ports and fewer chandleries or auto-parts stores — I was faced with a leaking heat exchanger end-plate gasket. An impeller failure had forced the removal of the cover plate for cleaning, and in the process, the gasket was damaged. No amount of “form-a-gasket” (more on this in a moment) would hold up in the damaged area for more than a day of running. Ultimately, after turning the boat upside down for suitable material from which to make a gasket, I used the cover of the HO 249, the sight-reduction table. It was nearly the same thickness as the original gasket, and once slathered with sealant and compressed, it remained liquid-tight for the remainder of the passage. It wasn’t a perfect solution, but it worked until a proper gasket could be sourced.

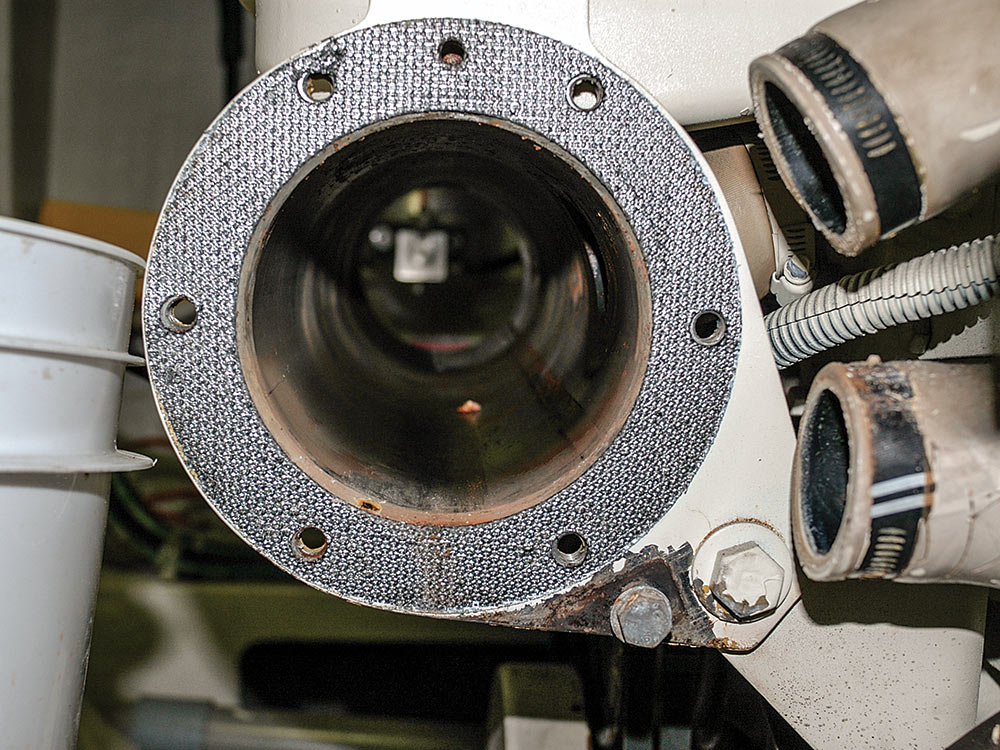

Ideally, however, you’ll want to carry the most common gaskets (and/or O-rings), such as those used for the heat exchanger; and raw-water-pump cover plates; fuel pumps; raw-water-pump flanges (if gear-driven); and valve covers to name a few. Depending on your skill level, and how far you’ll venture from parts resources, you might also wish to carry oil pan, exhaust, intake manifold and head gaskets.

Paste or form-a-gasket compounds are also a valuable resource because they can be used either to make a gasket you otherwise don’t have or to replace original equipment self-forming gaskets that are damaged, as they almost always are during disassembly. Many modern engines forgo conventional gaskets altogether, relying entirely on self-forming gaskets. Those used in engine applications are typically known as RTV-S, or “room temperature vulcanizing silicone,” a versatile material that’s available in a wide range of options, from ultra-fast-setting (these can be used literally one minute after assembly) to high temperature (up to 700 degrees Fahrenheit) to applications such as exhaust manifolds and turbochargers.

Paste RTV-S is often used to augment conventional fiber gaskets, improving leak resistance; however, this approach may be problematic because there is a difference between a form-a-gasket compound, one that’s designed to act as the sole gasket, and a “gasket dressing,” a compound designed to augment the properties, extend the life or improve leak resistance of conventional gaskets.

Furthermore, some gaskets (for instance, those used for cylinder heads) are designed to be installed dry. In cases where I’m concerned about leaking on an older installation, I have used aerosol spray-on copper-based gasket material, which is designed for applications of this sort.

Next month I’ll cover making your own gaskets and proper gasket-installation technique.