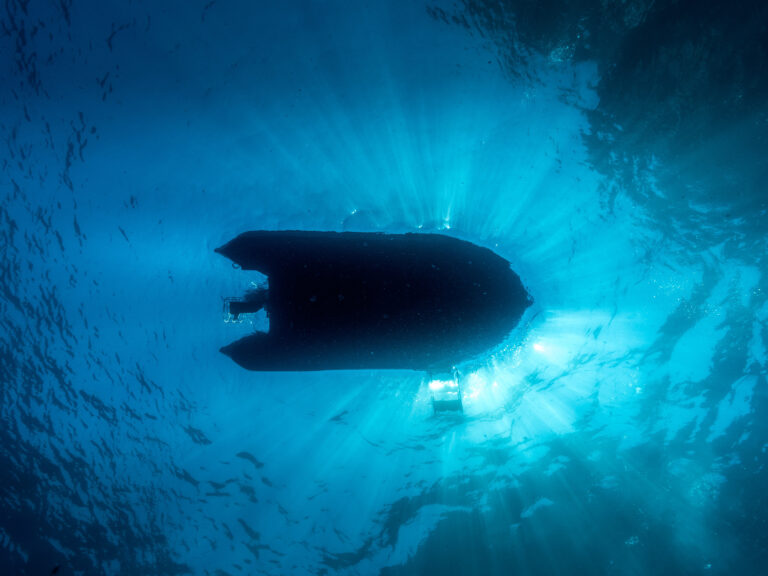

Haulouts are a necessary evil. They are the only time a boat owner can perform a thorough inspection of the hull, rudder and underwater hardware, as well as apply bottom paint and perform other below-the-waterline maintenance.

There are several ways to make the most of this process. Here are a few tips.

Keep the Water Out

Watertight integrity rises above all other priorities. The weakest links in this chain are hull fittings and seacocks. That’s why it’s important to use time on the hard to inspect each one.

If they are metallic, then scrape off some paint. The metal color should look like copper. While the telltale green shade of verdigris is not harmful, any sign of a pinkish hue is cause for concern. Pink indicates de-zincification. It means the metal is brass, which contains zinc, rather than bronze, which does not. The former is definitely not suitable for use in seawater.

Work all the seacocks, and replace any that are seized. Those that are stiff can often be freed with exercise and a little penetrating oil. Most modern ball-type seacocks use Teflon or other synthetic seals, which don’t need lubrication, however, those that have drain plugs can usually accept Zerk fittings, which allow the void around the ball to be filled with grease, making movement easier.

Stay On Course

Closely inspect the rudder for damage, and remember to look at the very bottom surface. Many rudders “leak” water while hauled. This might not be cause for concern. However, if the liquid is rust-colored, then water may have penetrated to the rudder’s internal metallic support structure. That structure might be stainless steel or a combination of stainless and mild steel (the latter is undesirable, but both can suffer). If corrosion is present, surgery might be necessary to avoid a parting of the ways between the rudder stock and blade—and the resultant loss of steering or the rudder altogether.

If the rudder is skeg hung, then check the condition of the gudgeon, the stationary support for the rudder’s lower pivot point, called the pintle. It’s normal to have a small amount of lateral play here, but too much can indicate wear or damage. Fiberglass around the pintle hardware should be free of anything other than minor gelcoat surface cracks.

With spade rudders (those that are not supported at the bottom), grab the lowest portion and push-pull it to port and starboard. A small amount of play is normal where the rudder stock enters the rudder log, tube and bearing that provide support at the hull interface. Excessive movement can indicate wear and the potential need to replace the bearing. Both rudder types should otherwise move freely to their stops without binding.

Keel and Stub

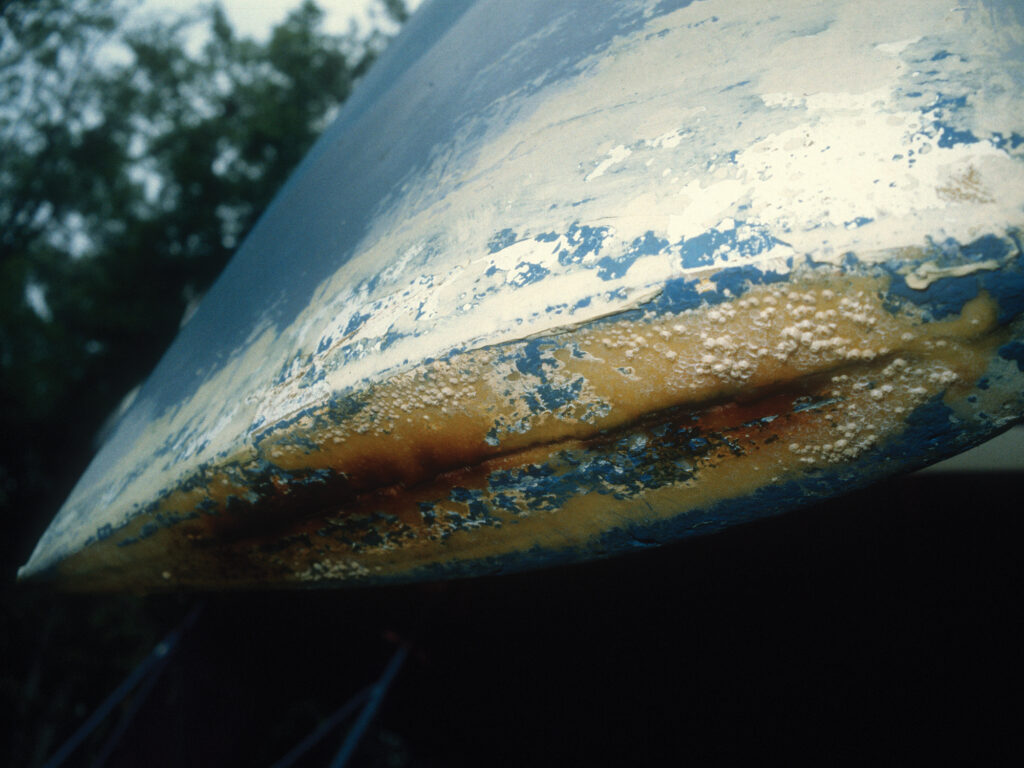

Have a close look at the keel, especially if it is externally ballasted. Trouble can lurk in the interface between the ballast and hull, which might be direct or might rely on a fiberglass protrusion called the stub. It’s not unusual to see some water leaking from this interface, but if it is rusty in color, it indicates corrosion to keel fasteners, which are typically made from a stainless alloy.

How much corrosion has occurred is impossible to know without separating the keel from the hull, but there have been a few high-profile cases of keel loss, often with fatalities, so better safe than sorry.

Dropping an external ballast keel is no small undertaking, but for a skilled yard, it should be fairly routine. If the keel is externally ballasted and it is cast iron, the integrity of the coating is critical. Any breach will lead to rust, which will spread. Correction requires cleaning, grinding to bright metal, and then coating with an epoxy primer rather than simply applying antifoulant.

For all keels, check the bottom for grounding damage. If the keel is internally ballasted, then severe grounding damage can allow water to reach the ballast. This is problematic for lead ballast and especially concerning for iron ballast, which will rust and expand, damaging the fiberglass structure. Better to catch this problem early. —Steve D’Antonio

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.