In temperate latitudes, sailing traditionally has a season: summer. When the leaves start to fall and frost starts to form, sailors typically go about storing their boats for the winter. In places where the harbor freezes hard, this means hauling out of the water. In New England, yacht clubs and boatyards haul their floating docks out of the water too. All this makes sense, of course: No one wants ice to damage their boats and docks. But if you live somewhere just mild enough that the harbor might not freeze over—or even if you would just like to extend your sailing season as long as possible before your harbor does freeze—it’s quite possible to sail comfortably in the cold months. And if you’re up for adventure, there’s some remote and challenging cruising to be had in the coldest regions of the world.

My husband, Seth, and I have had a decent amount of practice sailing in less-than-ideal temperatures: an unusually severe winter that we spent living aboard our 40-foot cold-molded wooden cutter, Celeste, in the Pacific Northwest; high-latitude voyages to the Arctic and Alaska; and, our introduction to offshore sailing and first exposure to cold-weather sailing, a voyage from Maine to North Carolina in December in a boat without heat or insulation. On all of these voyages, we’ve found that the key to enjoying cold-weather sailing is to prepare adequately, both in terms of safety and comfort.

Note that there are certain items and practices that are common to all latitudes and seasons, including having proper lifesaving equipment on board such as life jackets and harnesses and reliable bilge pumps, and preparedness in personal safety skills such as man-overboard drills. I won’t go into the basics of offshore safety, but here are some tips unique to sailing and living aboard in the cold.

Clothing

There’s an often-quoted saying attributed to a host of different cold-weather places: “There’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing.” As smug as it is, it’s also true. With the right clothing, cold and wet weather can be tolerated and even enjoyed. Even with all the advances of our technological age, wool remains the best insulator: My cold-weather-sailing wardrobe consists of layers of wool long underwear, wool sweaters, wool socks, wool gloves and wool hats. The great advantage of wool is that it will keep you moderately warm even if it gets wet. Obviously, you won’t be as warm as you are when you’re dry, but your wool clothing will not sap the warmth from your body in the way that cotton does. Down is also a superb insulator—and synthetic downs have improved tremendously—but down needs to stay dry in order to work. Which brings us to waterproof clothing to keep out the wet.

Foul-weather gear is a great example of how modern technology has enormously improved our options. All the major brands produce superb—albeit pricey—jackets and bibs, trousers, and salopettes. Gore-Tex was one of the first waterproof-yet-breathable fabrics, and now many of the brands have proprietary equivalents. These all seem to work very well, especially the top-of-the-line models. My current kit includes the top-end Helly Hansen Aegir jacket, which has kept me warm and dry for over 20,000 miles. The Aegir jacket’s effectiveness is also thanks to its good fit for a woman: When I first started sailing offshore, women’s bluewater clothing options were all so boxy and bulky that they often didn’t keep the wind out very well. I’ve found that my top-of-the-line jackets, regardless of brand, have generally held up better than the less-expensive coastal jackets I’ve had. My experience has been that no matter what the brand—Seth and I have used Musto, Henri Lloyd and Gill, as well as Helly Hansen—the waterproofing does eventually decline with age and use. For the top-end line, that tends to take about 30,000 miles of ocean sailing. I’ve found that the coastal models, when worn as offshore foul-weather gear, tend to hold up for about 10,000 miles.

Once you’ve settled on your base layers and foul-weather gear, make a plan to protect two other important parts: hands and feet. Hands are tricky, because you need to retain dexterity for reefing, trimming sails, steering and a host of other tasks. I haven’t found one good solution yet, so I use a bunch of different gloves and mittens. For hauling up the anchor, for example, Seth and I use insulated rubber fishermen’s gloves. For simple steering, or for long hours on watch without many tasks to perform, well-insulated waterproof mittens are in order. For tasks requiring a lot of fine motor skills in a short amount of time, I have yet to find anything better than unlined fingerless wool gloves. They can easily get wet when you’re on deck near the mast, reefing down, so I keep several pairs on board and always have a dry pair ready.

Feet are easier. There are lots of options for waterproof boots, and one’s choice just depends on personal preference. Mine is for neoprene insulated rubber boots such as XtraTuffs; Seth’s preference is for simple boots without insulation so that he can regulate the warmth with wool socks. Others prefer Gore-Tex-type boots such as Dubarrys. As long as your feet stay warm and dry, you’ve found a solution.

Warm Cabin

Having a warm place to retreat to when you come off watch makes a huge difference to crew morale—and also, potentially, to safety. Being constantly cold saps you of energy and can lead to lethargy and poor decision-making. Everyone gets better rest if they are warm, and this will improve both the safety and enjoyment of the cruise. The first step to this is easy and can be accomplished in any boat, provided the boat doesn’t leak: a warm, dry sleeping bag. Seth and I have three bags—a down one rated to 0°F and two synthetic-down bags rated to 20°F—as well as a heap of thick, felted wool blankets.

Of course it’s better to have options in addition to your sleeping bag. If you have the electrical storage or generating capacity, one of the best heating options is a forced-air heater like an Espar. These use diesel to make heat, and then use electricity to pump the warm air through ducts and vents throughout the cabin. Our heater can get Celeste up to a comfortable temperature in only about 15 minutes. However, it does use a significant amount of power, and so we also have a gravity-fed diesel heater. Ours is a Danish Refleks stove; Dickinson also makes these. They use no electricity and put out a really good amount of heat. They dry out the cabin nicely, and some models are built so that you can cook on top of them. If you are motoring a lot, it also makes sense to install a little bus heater that uses the engine’s heat exchanger and a little radiator to warm the cabin.

Hot Meals

A good way to warm up and have renewed energy is to eat something hot. Normally Seth and I cook regular meals in our galley; we often have hot meals three times a day. When the weather gets really unpleasant, however, the way we accomplish this is to heat up something easy. This might be a can of soup, or a jar of a homemade chili or stew that I prepare and then preserve in my pressure canner before passages. If conditions are really rough, we eat camping meals into which you need only to pour boiling water and wait 10 minutes. Our favorite quick meals are AlpineAire meals—there’s a lot of variety to the meals, and they’re all quite nutritious. A mug of hot chocolate or a thermos of tea or coffee is also great to sip on during a cold night watch.

Safety

The stakes are higher when sailing in cold weather or high latitudes than they are in warm conditions, so it’s a good idea to take extra safety precautions. Again, I’m not going to get into things such as jacklines and life rafts and radios, which are good ideas in all conditions. But there are a couple of things that make good additions to your boat’s safety kit in the high latitudes. Survival suits for each crewmember is one such addition. The US Coast Guard requires commercial-fishing vessels to carry these in waters north of 32°N on both Atlantic and Pacific coasts, which is about the latitude of San Diego, California, and Savannah, Georgia. San Diego typically has water temperatures of about 60 degrees, which can lead to hypothermia quicker than you think. In 50-to-60-degree water, one’s expected survival time is between one and six hours. Immersion suits sound like a pretty good idea, even if you have an insulated, covered life raft.

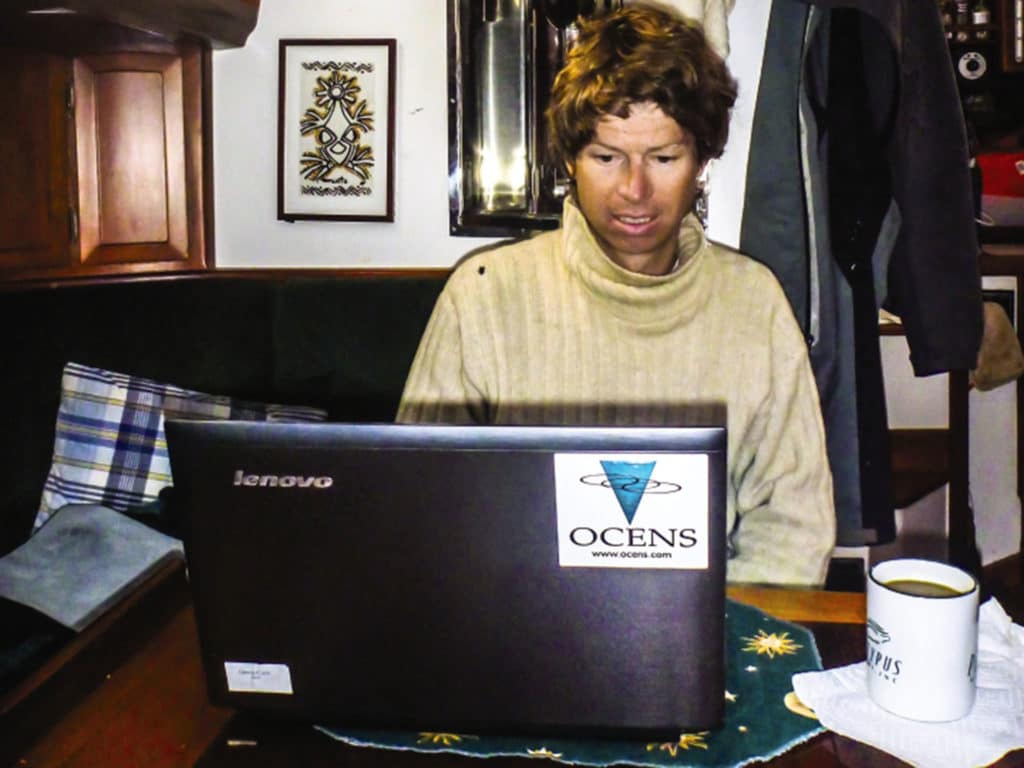

Prevention is always better than a cure, however, so to my mind, safety starts with deciding whether put out to sea at all. And once at sea, the ability to receive good weather forecasts is crucial. For our voyage to the Arctic, Seth and I equipped Celeste with an Iridium satellite phone and OCENS Sidekick router, through which we could receive weather charts and sea-ice charts from OCENSWeatherNet. This enabled us to plan our passages even when we were anchored in remote places where there was no internet or phone connection. Once underway, we were able to keep track of any adverse weather developing and act accordingly. We changed our routes several times thanks to the information we received: ducking in behind protective headlands when gale-force headwinds were predicted; heaving to and battening down the hatches when a strong gale blew up against us in the middle of the Bering Sea; and staying an extra couple of days in one port when it was clear that wind and current would be setting strongly against us.

RELATED: Birdwatching by Sailboat in Alaska’s Northern Waters

Regarding the boat itself, it’s good to be sure that your vessel is up to the conditions in which you’ll be sailing. You can go for pleasant winter daysails in any boat; indeed, “frostbiting”—racing dinghies in winter—is quite popular in New England. For extended voyages in the cold and harsh conditions of the high latitudes, however, you’ll want to be sure that your boat has certain attributes. It needs to sail well to windward and therefore have a chance to claw its way off a lee shore, should that terrible situation come to pass. It needs to have a very strong hull if you’re taking it into ice. It should preferably have an insulated cabin to retain heat, and it needs to be free of leaks. Nothing turns an enjoyable voyage into a misery like a cold, persistent leak over a bunk.

Finally, it’s essential to have a good crew for cold-weather sailing. Because the conditions are so much more demanding than they are for summer or tropical sailing, it’s even more essential that the crew get along well with each other and work happily together. Indeed, a positive outlook is perhaps the biggest key ingredient to a successful cold-weather voyage.

Then again, there’s always the option to head south. Antigua, anyone?

Writer and photographer Ellen Massey Leonard has sailed nearly 60,000 miles on rudimentary classic boats, including a circumnavigation via the Cape of Good Hope, a voyage to the Alaskan Arctic, and three crossings of the Pacific. She and her husband, Seth, were the 2018 recipients of the Cruising Club of America’s prestigious Young Voyager Award.