Anyone with a Bermudan rig knows how tricky it can be to keep the sails filling and holding a steady course when running before a good breeze, especially with a big sea rolling up astern. Preventer poles and various lines are typically needed to hold the sails out, yet even with these, the helmsman must constantly adjust to prevent sail collapse. Poled-out twin headsails are difficult to reef, often requiring crew to go forward at the worst possible time.

With a squaresail correctly braced, these issues are eliminated. The boat remains stable, and the sail stays full even if the helmsman deviates from the course. A monohull rolls less because there are no opposing forces like with twin headsails. Having sailed on square-riggers, I decided to fit a squaresail on my 50-foot schooner, Britannia.

A key challenge with a large, flat sail high on a mast is how to reef or furl it. Traditionally, sailors climbed the rigging to manually secure the canvas. Since my wife adamantly refused to scale ratlines, I needed a system to control it from the deck or, ideally, the cockpit.

In squaresail terminology, the horizontal spar is the yard, with the section outboard of the lifts called the yardarm—the infamous site of hangings. The outermost footrope, the Flemish Horse, earns its name when you’re balancing on it at the end of a swaying yard. In heavy weather, reefing or furling a squaresail feels like riding a wild bronco, and the “horsemen” of old were the elite topmen.

But on Britannia, there’s no need for Flemish Horses, leechlines, buntlines, bowlines, clew garnets, or tack lines—all essential for a traditional squaresail. Instead, I have two cockpit lines: “squaresail up” and “squaresail down.” Here’s how it worked…

I’ve sailed with different squaresail systems—one that hauled the sail along a yard track like drapes, another hoisted only at the center and ends. Both worked but couldn’t be reefed. I also considered a roller-furling system mounted horizontally in front of the yard. It allowed reefing but added stress at the yard ends, requiring a heavier spar, and left the sail exposed to the elements.

The ideal solution? Housing the sail inside the yard, like in-mast furling. This would allow infinite reefing, even load distribution, reduced windage, and protection—though achieving it seemed like a tall order.

BUILDING THE YARD

Before designing, I needed answers—how big should the sail be? Marine architects and sailmakers couldn’t tell me the ideal yard length, sail area, or added stresses on the mast and rigging. I finally found a formula for yards and sails in the archives of the Old Naval Dockyard in Chatham, England. It was all I had to go on.

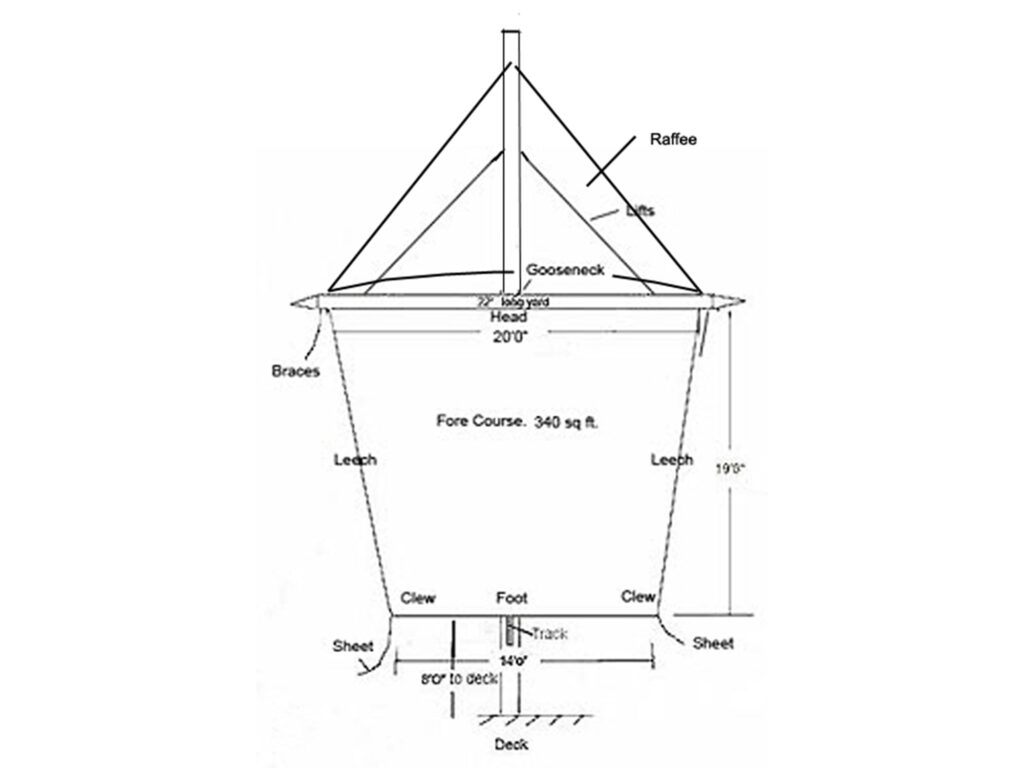

Before building, I needed a strong 22-foot-long tube with a continuous slot for the yard. Inspiration struck when I considered in-mast furling—why not repurpose its extrusion? To determine the right size, I rolled a 19-foot strip of sailcloth around a mandrel, yielding a 5-inch diameter, so I sought a mast section with a 5½-inch internal diameter.

After multiple rejections, Charleston Spar in North Carolina agreed to sell me a suitable extrusion, plus a rope-operated furling drum and mandrel. Conveniently, I could fabricate the yard at my daughter’s warehouse in Hickory, just 50 miles away.

With ample space, I used a skill saw to remove the mast’s front section, alarming warehouse workers. I then added welded lugs for rigging attachments. After shaping the ends, I fit the furling drum snugly inside, secured the mandrel with a thrust bearing to reduce sag, and carved removable cedar end caps for access.

After much labor and a pile of aluminum shavings, I had a yard.

THE SAIL

I needed a sail but didn’t want to invest in Dacron before testing the system. Instead, I made a trial sail from a plastic tarp, gluing the edges.

Rather than a perfect square, I designed a trapezoidal shape—20′ wide at the top, 14′ at the bottom, and 19′ tall (350 sq. ft.). This allowed the leeches to roll smoothly inside the yard without bunching or jamming.

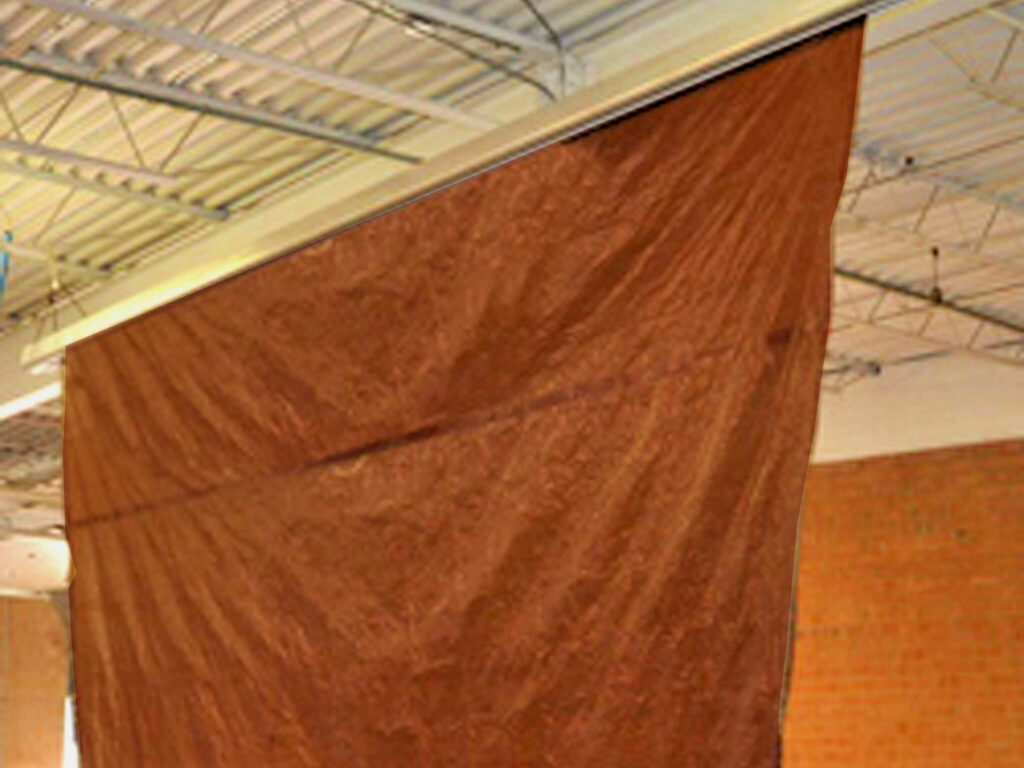

Eager to test it, I considered hoisting it on a telegraph pole outside the factory, but my daughter vetoed that idea. Instead, I rigged it inside the warehouse, using pulleys and large industrial fans. It worked—rolling up and down smoothly.

Next, I needed a gooseneck to attach the yard to the mast, allowing it to pivot for bracing and rotate for docking. A modified spinnaker-pole end on a traveler car did the trick.

At last, I strapped the yard to my SUV’s roof rack and set off on a nerve-wracking 650-mile drive to Britannia in Florida, relieved when both I and the yard arrived intact.

RIGGING

While taking a break from construction, I rigged lifts and braces on Britannia to control the yard. Concerned about the added load of a 130-lb spar swinging 35 feet up, I reinforced the foremast with new 3/8” stainless lower and cap shrouds, plus 30-degree-angled spreaders. I also added running backstays anchored to pad-eyes aft.

The winding drum lines ran along the yard, down the mast, and through blocks to the cockpit, allowing the sail to be furled and unfurled remotely. To the amazement of fellow sailors, I hoisted the unusual spar, and even more remarkably, a green and brown sail appeared and disappeared from the tube—without anyone touching it—thanks to cockpit winches.

A TRIAL SAIL

We motored into the Intracoastal Waterway for a trial. After turning Britannia downwind, I carefully hauled on the “down” line, and my makeshift sail unfurled. As we hauled in the sheets, Britannia gradually picked up speed, reaching four knots with only a light following wind. Zack, my 11-year-old grandson, asked to steer—something not usually entrusted to a beginner. I handed him the wheel and watched as he zigzagged, oversteering like most first-timers. Normally, this would be a problem with fore-and-aft sails, but the squaresail remained full despite Zack’s erratic course. It was a successful first trial.

Having invested significant time and money, I now faced the most expensive part: a real sail. However, I couldn’t find a sailmaker experienced with squaresails, let alone one that could fit inside a five-and-a-half-inch tube. Doyle Sails in Stuart, Florida, showed the most interest, so I placed the order. When the new sail arrived, the final stage of the experiment could begin.

THE DAY OF RECKONING

The breeze was perfect, ten to fifteen knots straight down the Intracoastal Waterway. We motored upwind for a while, then turned around, and I cut the engine—this was the moment of reckoning, a year in the making.

As helpers handed me the squaresail sheets, I hauled on the “down” line, and the sail began to unwind from the yard. The wind caught it, and it started to unroll on its own, but I controlled it by cleating the “up” rope and easing out more sail. Soon, the full 350 square feet billowed before us. The sheets were winched home, and I felt the boat pick up speed. Seeing the beautiful white sail fill so well was exhilarating.

Britannia hardly rolled at all; the motion was more like a catamaran than a monohull. I steered confidently through the narrow gap under the first fixed bridge, which seemed tight with my 14-foot boat now 25 feet wide. A speedboat passed us, and the people shouted, “Fabulous!” “Great show!”—I felt incredibly proud.

Unfurling the sail was easy, but would it roll back smoothly with the wind still in it? At that moment, I hoped it would. There was only one way to find out.

As my crew eased the sheets, spilling some wind, I winched the “up” rope and started winding the sail back into the yard. It was harder than unfurling but got easier as the sail reduced in size, eventually disappearing into the yard “as clean as a whistle!” Another milestone passed—what a relief! The ability to stow or reef the sail was a major reassurance if the wind picked up.

Next, I wanted to see how many degrees we could sail off the wind. I steered a zigzag course downwind, bracing the yard to port and starboard by 30 degrees. Amazingly, the sail never lost wind, even when three points on either tack. This gave us more flexibility when sailing downwind with a big following sea, which would normally try to broach a Bermudan-rigged boat. It also meant less work for the electric autopilot.

The trial was the successful result of considerable effort and expense, so we celebrated with Champagne as we headed back to the marina. And no, the bubbly didn’t make me forget to cant the yard before entering the berth. It was a very satisfying trial of my new invention.

Months later, after getting more familiar with the sail’s characteristics, Britannia surged up the Intracoastal at eight knots in 30-knot southerly winds, as steady as a catamaran. This was something I’d never have dared in such a confined waterway before—I would usually anchor and wait for the wind to calm.

The red cross on the white squaresail is the flag of England, part of the Union Jack, as well as the emblem of the Red Cross and the Templar’s Cross. It adds to the mystery as my “little” tall ship is spotted on the horizon.

THE COST

- Winding drum: $600

- Yard and mandrel: $400

- Gooseneck and track: $380

- Sail: $1,550

- New ropes: $400

- Subcontract welding: $200

- Ancillary equipment: $206

- Total: $3,736

Boating projects often come down to what you want and what you’re willing to do to achieve it. Though my family thought I was nuts, when I see my beautiful squaresail billowing forth, I know it was worth it. My small square rigger is now truly unique.