Rigging and spars live a hard life. They are fully exposed to rain, salt, and ultraviolet rays for years on end, along with extreme cyclical compression and tension loads. Considering the poor condition of many rigs I inspect, it’s a miracle that so few fail catastrophically.

It’s even more astonishing when you add the opportunities for corrosion that are peculiar to a primary alloy used in rigging and spars: stainless steel.

Stainless steel—as robust, durable and indispensable as it is—is not without its weaknesses. Superman’s nemesis is kryptonite. Stainless steel’s nemesis is far more common. It’s stagnant water.

Stainless steel’s largest alloying element is iron, but it achieves its legendary corrosion resistance thanks to the addition of several other metals, which vary depending on the alloy. They can include nickel, chrome and molybdenum, in varying percentages, among others. The more exotic the stainless alloy, the more elements it usually contains.

This metallurgical cocktail lets stainless steel form a tough, clear oxide coating as it is exposed to air. The coating is maintained as long as that exposure continues. In most cases, even the oxygen dissolved in moving water—fresh and salt—is adequate for stainless steel to maintain its corrosion resistance.

Why, then, are instances of corroded and failed stainless steel so common with everything from fasteners and rigging wire to turnbuckles and plumbing components? The answer is air. Deprive stainless steel of its constant exposure to air, and things go awry.

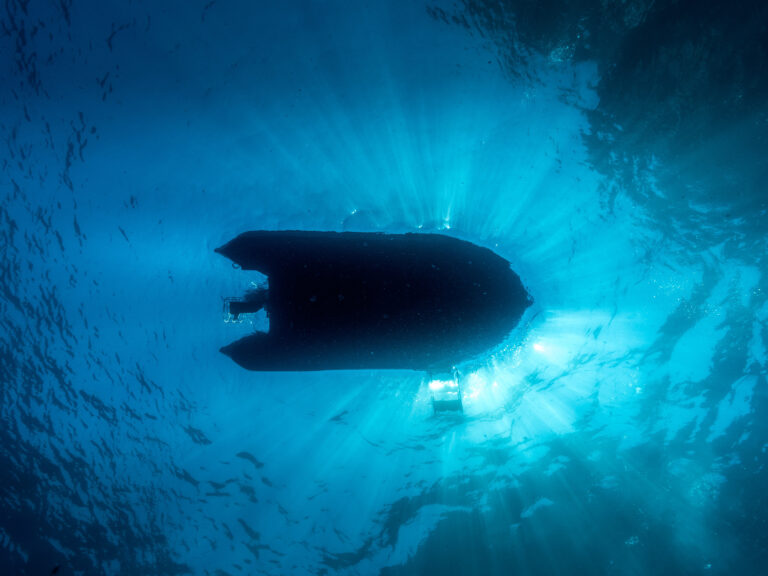

Once starved of oxygen, stainless steel goes from a passive to an active state. In other words, it begins to corrode. That’s why stagnant water is such a threat. The scenario can be as simple as trapping water against a fastener that passes through a deck or hull. Give it air, and stainless steel will survive.

Prevention is the best cure, and in the case of crevice corrosion, that means avoiding water entrapment. Make certain that all stainless-steel-flanged hardware is fully bedded, not just the fasteners in polyurethane or polysulfide sealant. Avoid wrapping or covering stainless wire rigging or other hardware with plastic, rubber, or other materials that can retain water. Where this is unavoidable, the wraps or coverings should be periodically removed so that the area can be dried, cleaned and inspected.

Stainless-steel fasteners that pass through hulls and decks, like those used for chainplates and padeyes, are particularly susceptible to crevice corrosion. Water can migrate into the hole that the fastener passes through. The fastener’s shank—the part that is not visible—is where the corrosion occurs. Make certain these fasteners are fully bedded, and remember that bedding and sealant have a finite life. After five to seven years, even the best product will need to be renewed.

One common error involves the act of bedding internal hardware, nuts, washers, and backing plates. This practice, while seemingly intuitive, will in fact facilitate the entrapment of water. Leaving these areas unsealed is preferable because if and when they leak, you know it’s time to rebed this hardware.

This is especially true of chainplates. The external portions and their fasteners should be fully bedded, including where they pass through the deck; however, internal backing plates or other support structures should not be bedded. Avoid applying fiberglass fabric and resin to stainless steel because this too acts as a water-trapping wet blanket.

The telltale sign that stainless steel has gone from passive to active is the formation of brown streaks, often called “tea staining.” If you see these stains, it’s a clarion call for action. Delay could lead to a rig or other hardware failure. —Steve D’Antonio

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.