My old Caribe Hypalon RIB dinghy had started to deflate, so I used a soapy-water spray to test for leaks. The forward-chamber air valve was leaking—not around the perimeter, where they normally do, but instead from inside the valve, indicating that it was not making an airtight seal.

I tried to clean the inside with a cotton ball and liquid soap, and that did reduce the bubbles a little, but not entirely. I also fitted a second sealing washer on the valve cap and squeezed it tight up to the valve face, but the boat still deflated over a few days. “You’ve got to replace the valve,” someone told me.

It was not what I wanted to hear, but off I went. I bought a Halkey-Roberts air valve from Amazon. It consists of an inner valve and an outer casing that screw together, clamping the valve to the chamber. I couldn’t loosen the old valve by hand, but I managed it after buying a wrench that fits inside the valve, enabling more turning force. It is best to do this with the boat inflated, which offers more solid support.

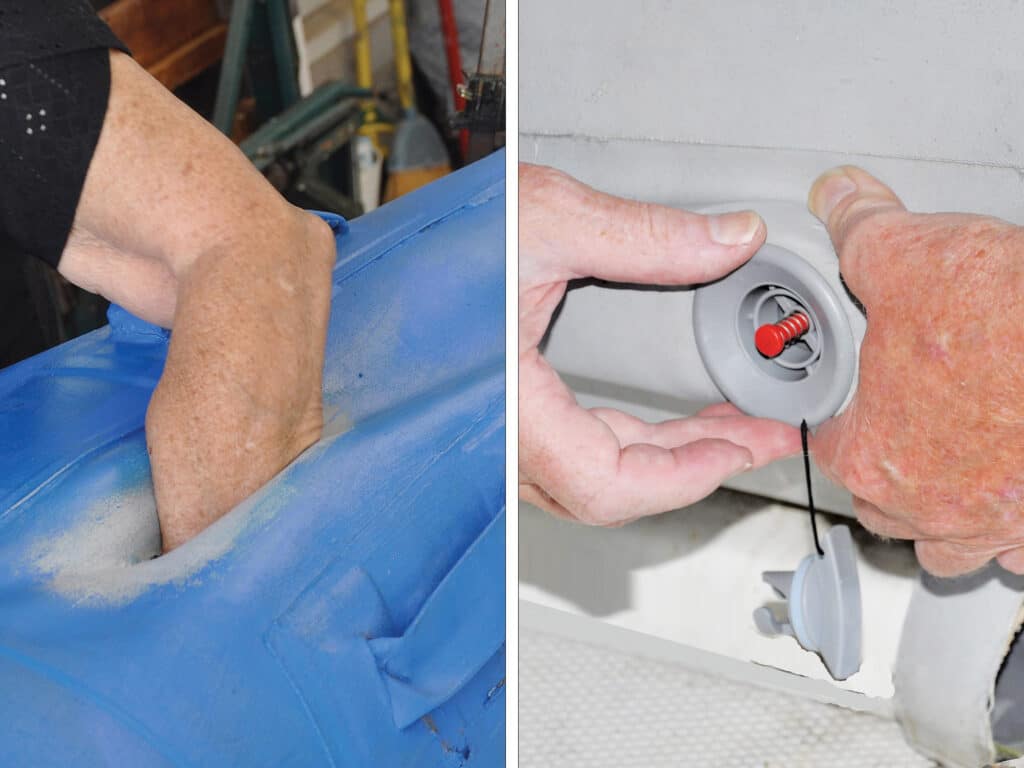

After fully deflating the boat, I gripped the inner valve body through the thick Hypalon material to prevent it from dropping into the chamber. Then I unscrewed the valve. I had the new part ready to screw back in, but after repeated attempts, it simply would not screw into the old body.

I struggled to hold the valve body with one hand while examining the old and new outer valves. The threads on the new valve were much finer than the threads on the old one. There was no way the new valve would thread into the old body.

Apparently, there are different types of Halkey-Roberts valves. With cramps setting into my fingers, I finally had to let go of the body. It fell into the depths of the chamber.

I called Halkey-Roberts in St Petersburg, Florida, and learned that they altered the valves more than 10 years ago. I asked if they could sell me an old one. Nope. They said I had to figure out how to fit the new body inside and screw it into the new outer valve.

This is decidedly easier said than done. The hole in the chamber is only 1¾ inches in diameter, and the valve rim is 2½ inches. There is no way the old valve will come out, or the new piece will go back in. The aperture is simply too small.

Looking for help online, I was dismayed to learn that the only way to get the new valve body inside the chamber was to slit a hole big enough to get a hand through, and then hold the body in place while screwing the two halves together. This means that anyone with an older boat that has Halkey-Roberts valves will have to replace a leaking one by slitting and patching the chambers.

More online research taught me that Hypalon requires a special two-part glue to bond a patch to the material. I bought a glue kit for $48.95, which is the most expensive glue I have ever bought in my life, plus another $38.95 for a 12-inch-square piece of patching material. So, along with $10.23 for the new valve and $9.45 for the wrench, the total came to $107.58.Quite an expensive leak.

I started the operation by donning rubber gloves and using acetone to remove blue paint from the dinghy. The work area was soon back down to the original gray material. Then, feeling like a surgeon about to perform the first incision on a very fat person, I used an X-Acto knife to cut a 6-inch-long slit in the dinghy chamber. My wife, whose arms are thinner than mine, reached in, found the old valve body in the bottom of the chamber, and brought it out. Holding the new valve, I then shoved my hand in, and managed to offer it up to the valve hole just below. I then screwed the two halves together and fastened them as tightly as I could using the special wrench, forming an airtight seal—I hoped.

I was told not to use any sealant—such as glue or silicone—between them, but instead just to screw them together, dry and tight.

All of this was relatively painless (after making the first incision, that is), but now came the job of patching the slot to make it airtight. The instructions with the glue were precise, with six specific operations.

The first directive warned that the humidity level should not be above 60 percent. With North Carolina suffering a heat wave that week, I waited, along with the dinghy, which was deflated and forlorn in my garage.

I made the cut in the top of the chamber, and there was nothing to support it inside, so I pressed two strips of duct tape under the cut seam inside the chamber to pull it together temporarily. I then smeared a thin layer of marine Goop glue along the cut and let it dry. This glue is ideal for flexible material because it stays quite flexible itself. I didn’t see any need to remove the Goop because even this weak seal allowed the chamber to inflate slightly, giving me some support as I prepared the patch.

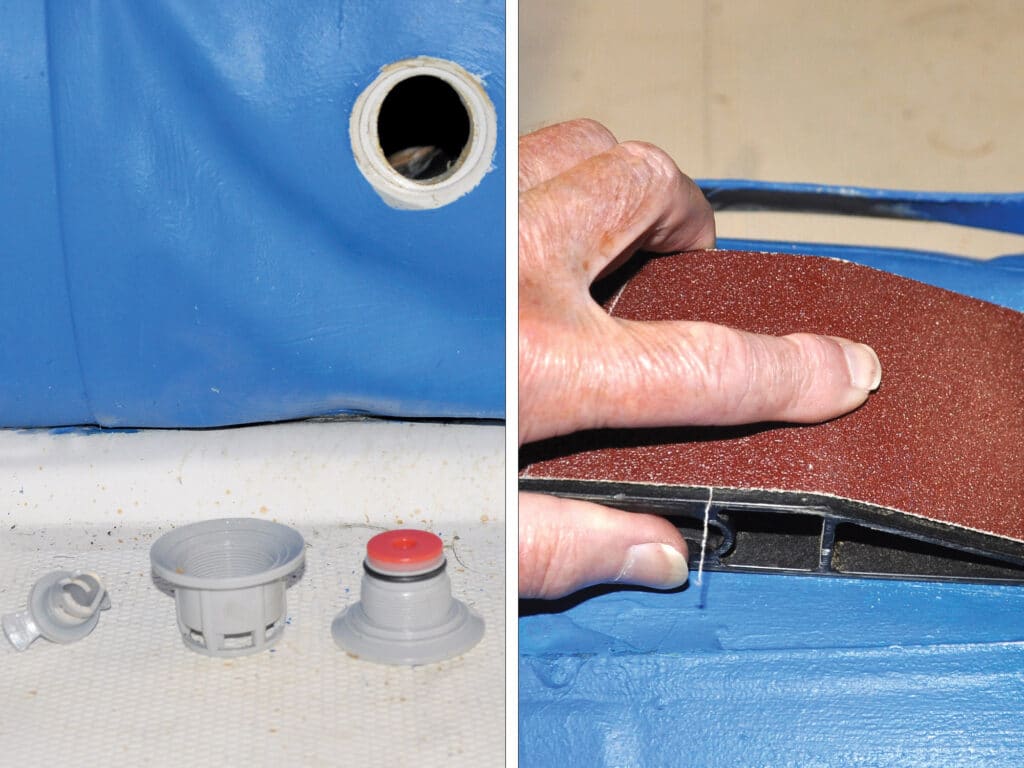

On the first cool, low-humidity day, I cut a patch out of the piece of Hypalon material, making it 1 inch larger all around the slit, and with rounded edges at both ends.

I prepared the surface of the chamber by roughing it with 80-grit sandpaper, exactly as instructed. I then poured some of the adhesive into a glass container and added the curing agent. This was pretty much guesswork because I had no way to measure the glue. One thing the instructions don’t mention is the type of container to mix the two parts in. Do not use a plastic or styrene cup because the glue will dissolve it. I used an old glass jar, which let me see how much glue was being poured.

Applying the glue is a two-part process. First, a thin layer is applied to the joint and the patch, which I did with a ½-inch-wide, stiff throwaway brush. I then allowed both pieces to dry. Half an hour later, a second coat is applied to both parts. After a few minutes, when the glue is tacky, the patch is glued to the boat. I did this by rolling the patch over the slit from one end to the other to reduce the chance of air pockets. The partially inflated tube allowed me to use enough pressure on the roller to expel any air pockets.

After an hour, I could feel the excess glue beginning to set, so I inflated the chamber a little more. To my surprise, no air came out of the patch or the new valve.

The next directive was to let the patch cure for at least 24 hours. I left mine for 48 hours, then inflated it to the recommended pressure of 3 psi. I also couldn’t resist testing the new valve with the soapy water. To my intense relief, it did not bubble at all, nor were there any bubbles around the patch.

The glue fully cures after six days, but I left my boat for a week before hoisting it back on the davits of my 50-foot schooner, Britannia. As I write this, the RIB has maintained pressure for a month, but it does vary a bit with the weather. It softens a little at night when the air is cooler, and then firms up during warm days.

This was another job that I had never done before and managed it myself. Not only is success gratifying, but I save a lot of money and learn the intricate workings of my boat, which might someday be a lifesaver at sea.

Roger Hughes is a professional captain, sailing instructor, restorer and happy imbiber.