Personal safety gear is more than a one-and-done purchase. For gear to be effective, sailors need to become completely familiar with it, and commit to a regular inspection and maintenance routine.

The onset of winter might sideline sailing, but it also affords an opportunity to reconsider personal safety gear. Start with a thorough cleaning and inspection of your kit. This includes the foul-weather gear, life jacket, tether, strobe, whistle and AIS beacon.

Consider replacing older, worn-out gear while adding some new kit. The goal is to have reliable, comfortable equipment that you’re willing to wear. It’s about function, not fashion. The value lies in how effectively this gear keeps you afloat, makes you more locatable, and wards off hypothermia.

One of the biggest misconceptions is that if an inflatable life jacket has never been used, it must be as good as new. This ignores the fact that such gear is regularly drenched with salt spray, cooked by the sun, then tossed into a locker and ignored. The best way to ensure operational reliability is to follow the manufacturer’s maintenance procedures. Look online for product updates or recalls.

A friend and safety expert recently surveyed other safety trainers and equipment experts about how often they encounter inflatable-life-jacket failures. One pro reported a 5 percent failure rate. Another said 11 percent. If aircraft had such a failure rate, lots more people would be taking the train.

Fortunately, there’s a way to beat those odds. It involves carefully scrutinizing key components while doing an annual, offseason inflatable-life-jacket inspection and maintenance.

Begin by checking straps and clips for signs of fraying or cracking. Open and unfold the device, removing ancillary equipment such as a strobe or an AIS beacon. Check battery expiration dates, and operate each device in its test mode.

Next, remove the carbon-dioxide cylinder and inspect it. Look for an intact seal on the cylinder, and note any signs of corrosion.

Then, orally inflate the life jacket and leave it overnight in a temperature-controlled environment. The next morning, check to see if there’s been a noticeable dimension change to the bladder. Even if you are handy enough to repair leaking seams on your inflatable dinghy or stand-up paddleboard, don’t attempt to patch a leaking life jacket. Replace it.

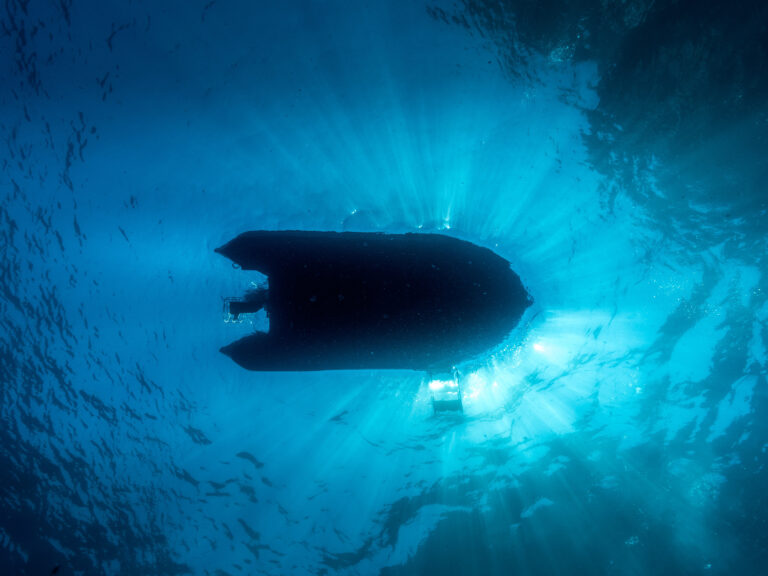

Note how many exhalations into the inflation tube it takes to fill up the life jacket—because if you’re submerged, water pressure will make the process even more arduous. If you go overboard untethered and the autoinflation feature fails, a reflexive tug on the manual-inflation tab can deliver the requisite buoyancy, or the last resort will be oral inflation.

Pay close attention to the autoinflator hardware, either the bobbin type or the hydrostatic system. The former relies on the solubility of a tabletlike compound, held in a bobbin, which dissolves when immersed. This allows a plunger to pierce the carbon-dioxide cylinder, inflating the life jacket. These bobbins can, over time and exposure to high humidity, harden and become less prone to dissolving. Follow the manufacturer’s recommended replacement timetable—often for annual replacement.

Hydrostatic inflation systems respond to slight changes in water pressure when the unit submerges. The pressure-sensing element must make full contact with the water—and in some cases, the plunge is not deep enough to activate autoinflation. The best bet is to follow US Coast Guard wisdom and treat these life jackets as manually inflated systems with an automatic backup. Train yourself to yank the manual-inflate pull tab immediately. If the autoinflate beats you to it, that’s great, but if the auto system balks, no problem—you have already initiated manual inflation, and you still have oral inflation as a backup.

Most sailors find that there’s no perfect life jacket. Inflatables are comfortable to wear in their dormant state, but it’s important to get into the water and experience the transition from deflated to inflated. See how swimming is affected. Discover how vital the leg and crotch straps are to maintaining buoyancy with your head elevated.

One of the best ways to accomplish this is to attend a US Sailing hands-on Safety at Sea seminar in a pool with pros. It’s another valuable offseason skill-building opportunity.

“Practice makes perfect” might be a bit of an overstatement, but familiarity with safety gear does improve outcomes. Getting to know your life jacket means that you have jumped into the water wearing it, done some swimming with it on, and even tried climbing up a boarding ladder.

If nothing else, find an indoor pool and a few fellow cruisers interested in gear familiarization. Dim the lights, and note how a bright flashing strobe on your vest or jacket destroys your night vision. (A light on a stalk might be preferable.)

Try the whistle, adjust the leg and crotch straps, and consider how an AIS beacon would be deployed. See if you could reach a mini flashlight or handheld VHF radio tucked into the pocket of your foul-weather gear.

Now is the perfect time, before the next season’s sailing begins.