Two teaspoons. Just 2 teaspoons of seawater can ruin your engine forever. That’s why I pay careful attention to my exhaust system, particularly pre- and post-gale.

It doesn’t matter if we’re on the way to New Zealand or heading across the Indian Ocean or rounding the Cape of Good Hope—I run my engine for an hour or two. Why? To dry it, its wires and my entire engine room. To get all its bearings lubricated (an engine that was run yesterday cranks quicker, easier and with less electrical drain than one that hasn’t run for 10 days). To monitor its operation and gauges so that I know it will crank if needed. And to ensure that my battery banks are fully charged and operational.

It’s not enough that my engine functions in calm and moderate conditions. I sail in the Pacific Islands. I cross the Atlantic. I’ve been in gales while crossing the Gulf Stream. I want my boat and all its gear to be ready for any condition that it might realistically encounter. This takes hard work and continual attention to detail.

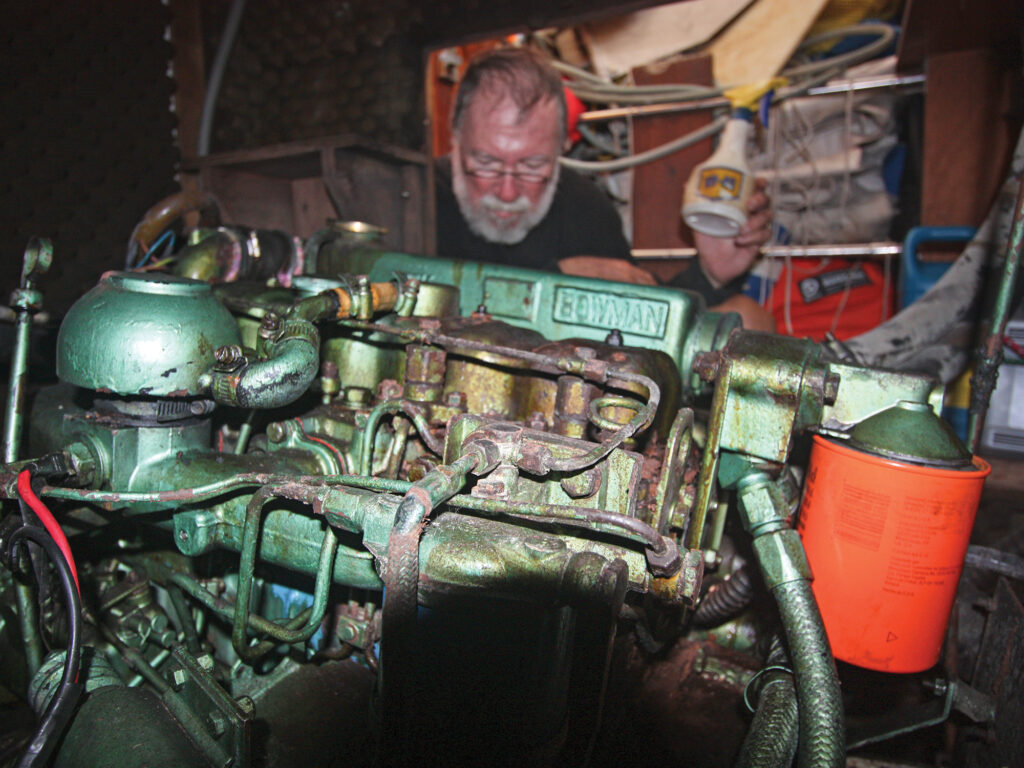

Example: Most of us world cruisers have a wet exhaust system. My exhaust hose is 3 inches coming out of my Perkins M92B diesel. To lower backpressure, it’s also 4 inches coming out of my wet muffler and exiting my hull. This means that a small cat could swim up to my exhaust port, crawl into it, swim through my muffler, and end up pawing at my cylinder ports inside my manifold.

My point is, that’s a fairly large hole. That hole is always fully open as I circumnavigate. And if 2 measly teaspoons of seawater manage to make the same journey as that cat, I don’t have an engine and I’m financially sunk.

I know, I know, we blow-boaters don’t like to think about stuff like this. We prefer to pray, chant, burn incense, and hold seances over our engines instead of maintaining them. But we must stay reality-based if we want our gear to work under adverse conditions.

A wet muffler is called wet because it mixes raw (sea) water with exhaust gases as the engine runs. Big mufflers cost more than small ones. Space is at a premium in most engine compartments, and unrequired weight on a sailing yacht is a no-no. Thus, many production boats come with minimal-size wet mufflers.

Now, if your muffler and exhaust hose are directly in the middle of your boat, when you stop your diesel, the water in the short intake hose and the longer exit hose drains back into the muffler. This is a lot of water. But, truth be known, your muffler probably isn’t on the centerline. Neither is your exhaust hose, nor your exhaust port through-hull. And let’s not forget that your boat heels. Occasionally, it heels a lot. You might be motorsailing and shut off your engine as the breeze puffs up. The result will be much more water in your wet exhaust than normal.

My Wauquiez 43, for example, exhausts amidships on its starboard side. I’ve had this setup for 40-plus years. If I’m on port tack, that huge, long, 4-inch hose drains quickly. Alas, exactly the opposite happens on starboard tack. If I’m rail down, that hose contains much water that might overfill my wet exhaust more than my designer, builder and mechanical propulsion engineer would prefer. After all, they design these things in warm, safe, dry offices, and I occasionally use them in 28-foot seas off the coast of Africa when a sou’westerly bluster opposes the Agulhas current.

Now, running downwind in mature breaking sea while lying to a Jordan Series Drogue results in a fair amount of corkscrewing. And streaming a Para-Tech sea anchor under the same conditions guarantees an extreme hobbyhorse effect.

And, while I never sail for long at more than 45 degrees angle of heel—usually far, far less—I do heave-to with my lee toe rail awash for days on end.

The result is that I have a brimming pot of sloshing salt water just a foot below my engine’s open, 3-inch exhaust manifold—while large, breaking seas are picking up my boat and violently tossing it around.

This, dear reader, is why so many engines don’t crank up a week after a gale: because 2 teaspoons (or 2 gallons) of seawater managed to work its way into the cylinders.

Remember: The waves hitting a vessel during a mature gale weigh tons. And, occasionally, the boat gets almost airborne and then smashed down onto the water (with a force of over 15 tons, in Ganesh’s case). The spray in a 45-knot gale is traveling at 45 knots. Think “fire hose” in terms of force and speed.

And there I am aboard a boat with a hole in it that a cat can crawl through. Hell, it’s a miracle that my engine survives any gale.

There’s another consideration—this time on the cooling side of the equation, not the exhaust. Raw water comes in via a through-hull, passes through a strainer, goes to the raw-water pump, the heat exchanger and perhaps the oil cooler, and then makes a long loop upward. There, at its apex, resides a siphon break before it heads down and joins the exhaust gases just aft on the exhaust manifold.

The above process requires dozens of hoses, hose clamps and gizmos for an engine to run. If its siphon break doesn’t open, then the engine back-siphons and drowns.

Now, a number of times during a full gale, I’ve opened my engine room, turned on the light, and watched. There’s a lot of dynamic force involved despite the engine not running. The engine sways on its bed. Hoses, wires and fuel lines chafe. Generally, it’s an extremely damp environment. All recreational boats leak during gales (with the exception of steel yachts sans any openings, something I’ve personally never witnessed).

What to do? Well, probably the best, most practical advice is to do nothing unless you’re a storm-strutter or plan to sail in the high latitudes.

Some offshore boats have shut-offs on both the raw-water intake side and the exhaust side. Skippers simply close these as the wind gusts to 40 knots. I don’t recommend this because I’ve unexpectedly used my engine a number of times during gales when caught back, when something is jammed, and I need to remove the force ASAP so that I don’t lose the rig, or to avoid collision with another vessel. And, of course, we might need our engine during, God forbid, a person-overboard situation.

All offshore sailors parse these details differently depending on their concern level. I installed a drain plug in the bottom of my wet muffler and a Gen-Sep under my deck between the wet muffler and the exhaust through-hull before heading across the Indian Ocean. Overkill? Probably.

One thing we can all do without much effort is run our engine immediately after the gale abates. I first check the lube oil to make sure it’s not milky. Next, I listen as I crank it up. If it is slower, quieter or takes more time to crank, that’s a bad sign. The engine may have gotten wet inside. However, I pat myself on the back for having saved the engine by cranking it up well before it needed to be rebuilt or replaced. I then run it for a while to dry things out.

Of course, if your vessel rolls 360 degrees, then all the water in your wet exhaust is going to flow into your engine almost immediately. This doesn’t happen often; however, I’ve talked to seven cruising sailors who have rolled their vessels during my 64 years of living aboard and ocean sailing. Yes, I would have spoken to more, but those unfortunates are no longer around to chat.

And the sobering truth is that we offshore sailors not only want to be able to survive if our vessel rolls 360 degrees, but we also want our expensive diesel engines to survive as well.

Am I paranoid? Of course, I’m paranoid. That’s why I’m alive and dry and on my fourth circumnavigation at age 72. Because I sweat these details.

Numerous production boats that sail across the Pacific end up having engine problems on their way down to, say, New Zealand. This is because, during that notoriously rough passage, they sail through their first real kick-ass gale, and it reveals previously unknown flaws in their exhaust system.

My exhaust guru is a man named “Diesel Dan” Durban. He helped write the excellent Please Don’t Drown Me booklet that Northern Lights published. He writes: “Just because your exhaust system hasn’t leaked yet doesn’t mean that it won’t in the future—given an extreme set of circumstances.”

True.

Now, the reason I write this column, dear reader, isn’t to needlessly scare you, but rather to expose you to the engineering considerations of one of your vessel’s most vital components: its mechanical propulsion unit. These problems aren’t theoretical. They’re practical, everyday considerations for offshore sailors, be they conservative fair-weather sailors or the more thrill-seeking storm-strutters.

Here’s the truth: The vast majority of premature marine diesel engine failures are directly related to improper exhaust engineering.

Forewarned is forearmed.